Television in the United States

Jewish women have a long-standing, complex, and occasionally fraught association with American television. Since emerging as a mass medium in the early post-World War II years, television in the United States has figured prominently in the careers of a number of American Jewish women working both in front of and behind the camera. Moreover, television has provided a distinctive venue for contemporary American Jewish portraiture, in which women have played a strategic – sometimes problematic, sometimes redemptive – role, bolstered in the 1990s and 2000s by the cable and streaming revolutions and third-wave feminist activism.

Personas and Personalities

Jewish women have appeared in American television from the beginning in diverse capacities – from children’s puppeteer Shari Lewis (The Shari Lewis Show, 1961–1963) to “Trash TV” talk-show host Sally Jessy Raphael (The Sally Jessy Raphael Show, retitled Sally, 1983–2002), from an interview with Nobel Prize–winning scientist Rosalyn Yalow (Jewish Voices and Visions, 1985) to a documentary on the life of real estate magnate Leona Helmsley (A&E: Biography, 1995). Regular appearances on television have helped a number of American Jewish women become national celebrities. Among the first was Gertrude Berg, who, as the writer, producer, and star of one of the medium’s earliest comedy series, The Goldbergs (1949–1955, not to be confused with the like-named series of the 2000s, discussed below), figures as the doyenne of Jewish women in American television. The portrait of a lower-middle-class family living in the Bronx, derived from The Goldbergs popular radio series (1929–1946), became an archetype of New York Jewry for the first American television watchers.

As iconic as Berg’s portrait of Molly, the Goldberg family matriarch, was for early postwar American television, her persona was essentially anachronistic, harking back to the warm, nurturing, immigrant Yiddishe Momme of the prewar years. Subsequent Jewish mothers tended to toe the pejorative line that emerged in male-driven Jewish literature and stand-up comedy of the 1950s and 1960s, gaining traction in television through Nancy Walker’s nagging, meddlesome Ida Morgenstern in Rhoda (1974–1978) and resurfacing in Renée Taylor’s Sylvia Fine in The Nanny (1993–1999). How resilient the less sympathetic Jewish Mother stereotype remains is evident in subsequent permutations such as Jessica Walter’s Lucille Bluth in Arrested Development (2003–2006, 2013, 2018), Judith Light’s Shelly Pfefferman in Transparent (2014–) and, most ironically, Wendi McClendon-Covey’s Beverly Goldberg in the The Goldbergs (2013–), no relation to the original sitcom, based on the 1980s childhood of series creator Adam Goldberg.

Berg’s character was only one image of Jewish womanhood offered by the medium in its early years. However, during a period when most American Jews stressed the Americanness that they shared with fellow citizens over their distinction as Jews, these other Jewish women (along with their male counterparts) generally appeared unmarked as Jews before the television camera. Mary Livingstone performed with husband Jack Benny in a semiautobiographical situation comedy (The Jack Benny Program, 1950–1965), in which the Jewishness of the protagonists was never mentioned. The same was true of Dinah Shore, who demonstrated both her talent as a popular singer and her aplomb as a television host in variety shows The Dinah Shore Show (1951–1957) and The Dinah Shore Chevy Show (1956–1963). But for the viewer who knew that these and other women were Jews (likely rare in Shore’s case), their on-screen attributes could be understood as emblematic of American Jewish womanhood. The celebrity quiz shows I’ve Got a Secret (1952–1967) and To Tell the Truth (1956–1967), for example, featured among their panelists former Miss America Bess Myerson, opera singer Kitty Carlisle, and actor Phyllis Newman, who offered an image of American Jewish women as witty cosmopolitanites.

Berg herself popped up again in the short-lived sitcom Mrs. G. Goes to College (retitled The Gertrude Berg Show, 1961–1962). In general, however, Jewish representation in episodic television receded markedly until the intermarriage-comedy Bridget Loves Bernie (1972–1973). A Jewish woman wouldn’t take center stage again until Ida’s daughter Rhoda Morgenstern (played by Valerie Harper), who appeared in The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970–1974) and starred in Rhoda. Rhoda, who grew up in the Bronx before moving to Minneapolis (where The Mary Tyler Moore Show was set) figured as the earthy, comically displaced foil to WASP protagonist Mary Richards (played by Moore). When Rhoda was transformed into the title character of the eponymous spin-off series, a new comic foil – Rhoda’s younger sister Brenda (played by Julie Kavner) – was introduced. Brenda took up what had been Rhoda’s comic trope of self-deprecation, centered on insecurity about her physical appearance and frustration with her love life.

Most American Jewish female performers who have become prominent have done so through starring or continuing roles in sitcoms. These have included Barbara Feldon (Get Smart, 1965–1970), Bea Arthur (Maude, 1972–1978; The Golden Girls, 1985–1992), Linda Lavin (Alice, 1976–1985), Carol Kane (Taxi, 1978–1983), Rhea Perlman (Taxi; Cheers, 1982–1993; Pearl, 1996–1997), Estelle Getty (The Golden Girls, The Golden Palace, 1992–1993), Julie Kavner (Rhoda; The Tracy Ullman Show, 1987–1990; The Simpsons, 1990–), Roseanne Barr and Sandra Bernhard (Roseanne, 1988–1997, 2018), Fran Drescher (Princesses, 1990; The Nanny, 1993–1999; Living with Fran, 2005–2007), Renée Taylor (Dream On, 1990-1996; The Nanny), Mayim Bialik (Blossom, 1991–1995; Big Bang Theory, 2010-), Debra Messing (Will and Grace, 1998–2006, 2017–), Susie Essman (Curb Your Enthusiasm, (2000–2007, 2009–2011, 2017–), Jenny Slate (Parks and Recreation, 2009–2015), Lena Dunham and Zosia Mamet (Girls, 2012–2017), Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer (Broad City, 2014–), Rachel Bloom (Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, 2015–), Alex Borstein (The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, 2017–). Others made regular appearances as sketch or stand-up comics in variety, quiz, and talk shows – Totie Fields, Goldie Hawn (Laugh-In, 1968–1973), Marilyn Michaels, Gilda Radner (Saturday Night Live, 1975–1980), Joan Rivers, Rita Rudner, and in the 2000s Sarah Silverman, Amy Schumer, and Samantha Bee. These women’s comic performances project a wide spectrum of images of womanhood, ranging from the slinky, adventurous Agent 99 portrayed by Feldon in the parody espionage series or Lavin’s Alice Hyatt, a savvy, working-class, single parent, to the self-effacing, often raunchy stand-up humor of the corpulent Fields, reedy Rivers, or foul-mouthed Silverman and Schumer.

The genealogy of Jewish women performers in stand-up comedy has been especially strong. Eventually, as it did for Jewish men (Jackie Mason, Richard Lewis, Jay Thomas, Paul Reiser, Garry Shandling, Jerry Seinfeld, and Larry David), it led to stand-alone TV shows. Roseanne Barr was the pioneer here, with her self-named sitcom (which she also produced), on which she played a nominally half-Jewish, working-class wife and mother. (Barr was ignominiously fired, for racist comments, from Roseanne’s revival in 2018; the show was then renamed The Conners, 2018–). Bette Midler, in her short-lived Bette (2000–2001), played herself, and similarly hewing closer to their comic personas in the 2000s were Sarah Silverman in The Sarah Silverman Show (2007–2010) and I Love You, America with Sarah Silverman (2017–2018), Amy Schumer in Inside Amy Schumer (2013–), and Samantha Bee in Full Frontal with Samantha Bee (2016–). Finally, paying homage to and historicizing the stand-up trope is The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, in which the eponymous, if fictional, Miriam “Midge” Maisel (Rachel Brosnahan), with the help of butch lesbian manager Susie Meyerson (Alex Borstein), rises from stay-at-home housewife and mother to stand-up stardom in 1950s New York, much as actual “unkosher comediennes” (Sophie Tucker, Totie Fields, Belle Barth, Joan Rivers, among others) had done.

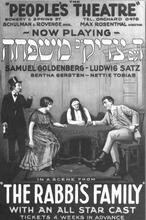

For many American Jewish women performers, television has played an occasional, variable role in their careers. Veteran Yiddish actor Molly Picon, for example, briefly hosted her own variety show on ABC in 1949. In the 1960s, she made guest appearances as a Jewish matron on situation comedies such as Car 54, Where Are You? (1961–1963) and Gomer Pyle: USMC (1964–1969), and appeared in the 1970s as a recurring character, Sarah Briskin, on the soap opera Somerset (1970–1976). In other instances, the medium has provided Jewish female performers with a distinctive venue for self-portraiture. Selma Diamond began her career in television in the 1950s as one of the few women writers for the medium, working on The Milton Berle Show (1962–1962, 1966–1967). A writer for Jack Paar when he hosted The Tonight Show in the late 1950s and early 1960s, she made occasional guest appearances on the talk show. Besides serving as the model for comedy writer Sally Rogers – a character (played by Rose Marie) on The Dick Van Dyke Show (1960–1966) – Diamond appeared on panel shows and acted in sitcoms (including Night Court, 1984–1992). Joan Rivers not only brought her self-reflexive humor to television audiences as a guest on variety, quiz, and talk shows, but hosted her own talk shows (including The Late Show, 1986–1988) and produced and played herself (as did her daughter, Melissa Rosenberg) in Tears and Laughter (1994), a television drama about the aftermath of her husband’s suicide. Although Barbra Streisand’s appearances on the medium have been infrequent, her occasional television specials and televised concerts (from 1965 through the 2010s) offer an evolving self-portrait as performer and as public figure.

While many American Jewish women have worked behind the scenes in news, cultural and public affairs broadcasting, relatively few gained a national on-camera presence on these programs. Most prominent is Barbara Walters, whose career spans several decades as a correspondent, news anchor, and host of a news magazine series (20/20, 1984–2004), a women’s talk show (The View, 1997–), and celebrity interview specials. American Jewish women who have reported regularly in network newscasts include Andrea Mitchell, Jessica Savitch, Lynn Sherr, and Nina Totenberg. Among the more prominent Jewish women involved in American cultural programming are opera star Beverly Sills, who hosted numerous public television broadcasts of operas and concerts, and Judy Kinberg, a producer of arts programming for public television since the 1970s.

Crypto-Jewish Women

The complexities of identifying a person or a character as Jewish in the modern world have further complicated the range of portraits of Jewish women on American television. Given that the signs of Jewishness in American culture are anything but simple or consistent, and that there is no consensus as to what these markers are, an examination of the presence of Jewish women on American television must also consider figures who are oblique, cryptic, even absent. This is particularly important given that the majority of American television’s portraits of Jewish women, at least until the 1990s, were the work of male writers, directors, and creators/showrunners. Therefore, with notable exceptions such as Berg and Diamond, co-executive producer Charlotte Brown and writer Treva Silverman on Rhoda, Roseanne Barr, The Nanny’s Fran Drescher, and Dream On and Friends (1994–2004) co-creator Marta Kauffmann, much of the medium’s representation of Jewish women must be read as the visions of men (who are often Jewish).

For example, one of the most memorable discussions of Jewish women in television—a 1970 installment of The David Susskind Show (1958–1986) devoted to the topic of Jewish mothers—featured the observations of comedians Mel Brooks, Dan Greenburg, and David Steinberg, along with other men, but no women. One of the most popular portraits of a Jewish woman on American television in the mid-1990s was the character of Linda Richman (who made the Yiddish term farklemt something of an American household word), created and performed by comedian Mike Myers on Saturday Night Live.

Another complicating factor in attributing Jewishness to women (and men) in American television is the frequent disparity between the Jewish identity of the characters and of the actors who perform them. Among the Jewish female characters in continuing series played by non-Jewish performers have been Rhoda and Ida Morgenstern (The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Rhoda), played by Valerie Harper and Nancy Walker; Phyllis Silver (the mother on Brooklyn Bridge, 1991–1993), played by Amy Aquino; Monica Geller and Rachel Green (Friends), played by Courteney Cox and Jennifer Aniston; Dharma Finkelstein (Dharma and Greg, 1997–2001), played by Jenna Elfman; Billie Frank (Rude Awakening, 1998–2001), played by Sherilyn Fenn; Lucille Bluth (Arrested Development), played by Jessica Walter; the Pfefferman daughters Ali and Sarah, and Rabbi Raquel Fein (Transparent), played by Gaby Hoffman, Amy Landecker, and Kathryn Hahn; Beverly Goldberg (The Goldbergs, later version), played by Wendi McClendon-Covey; and Miriam and her mother Rose (The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel), played by Rachel Brosnahan and Marin Hinkle. This common code-switching suggests that Jewishness is not regarded as an innate identity, but a performative one that can be realized (through accent, gesture, etc.) by non-Jews as easily as by Jews.

Conversely, Jewish actors frequently portray characters identified as non-Jews. In some instances, such as Elaine Benes (Seinfeld, 1990–1998), played by Julia Louis-Dreyfus; Dorothy Zbornak and Sophia Petrillo (The Golden Girls), played by Bea Arthur and Estelle Getty; Simka Gravas (Taxi), played by Carol Kane, these characters are often understood by some viewers as “crypto-Jews”—that is, characters who, while nominally identified as having some other ethnicity or religion, are nonetheless regarded as Jews in disguise. They are regarded as such not only by virtue of the performer’s identity, but also because of character attributes (such as being aggressive, neurotic, clever, or talkative) understood as signs of female Jewish behavior. This phenomenon suggests a larger sense of ethnic relativism distinctive to American culture.

Shiks-Appeal

Of special interest along the spectrum of Jewish women on American television is their strategic absence as characters, particularly in Jewish/non-Jewish intermarriages or romances in which Jewish men have been coupled disproportionately with shiksas (Yiddish for non-Jewish women). This gender-biased configuration had been established earlier in Broadway plays (notably Abie’s Irish Rose, 1924) and Hollywood films (for example, His People, 1925; The Jazz Singer, 1927; and film versions of Abie’s Irish Rose in 1928 and 1946). But intermarriage in U.S. society was rare until the 1960s, when an assimilation-fueled spike (from around five percent to over thirty percent in 1970) was reflected in the short-lived and controversial Bridget Loves Bernie (1972–1973), in which New York Jewish Bernie Steinberg (the non-Jewish David Birney) weds Irish Catholic Bridget Fitzgerald (Meredith Baxter). Jewish women gained a measure of revenge through Rhoda’s marriage to non-Jew Joe Girard (played by the Jewish David Groh), which met with considerably less controversy over the intermarriage issue, partly assuaged by the tradition of matrilineal descent in Orthodox and Conservative Judaism and the statistically noted greater likelihood that children of a Jewish mother will be raised Jewish.

Between the late 1980s and the early 2000s, over forty episodic shows with explicitly Jewish protagonists were produced, compared to ten or so in the previous forty years. In this period, the shiks-appeal pattern resumed with a vengeance. Such shows include thirtysomething (1987–1991), Chicken Soup (1989), Anything but Love (1989–1992), Seinfeld (1989-1998, which even titled an episode “Shiks-Appeal”), Northern Exposure (1990–1995), Mad About You (1992–1999), Curb Your Enthusiasm, and The O.C. (2003 –2007). Curb Your Enthusiasm’s resorting to a shiksa-based intermarriage was particularly striking given that the series was grounded in creator/star Larry David’s real life and that during its first few years Larry was actually married to Jewish producer/activist Lauri David.

A few major and minor reversals of the shiksa complex occurred during this period as well. Among the major were The Nanny’s series-capping marriage between titular nanny Fran Fine and non-Jewish boss Maxwell Sheffield (Charles Shaunessy), Dharma and Greg’s series-grounding union between ditzy, half-Jewish (on her father’s side) Dharma and white-bread Greg (Thomas Gibson), and Rude Awakening’s long-term affair between recovering drug addict Billie Frank and African American journalist Marcus (Mario Van Peebles). Of a more peripheral nature were Frasier Crane’s (Kelsey Grammer) wife Lilith Stern (Bebe Neuwirth) in Cheers; and the romance between Melissa Steadman (Melanie Mayron) and Gary Shepherd (Peter Horton) in thirtysomething. Significantly, however, all the Jewish women-based interfaith relationships except those in The Nanny, Dharma and Greg, and Rude Awakening end in separation or divorce, as had Rhoda’s to Joe Girard after one ratings-dipping season. Or they are dealt with posthumously, as in Everwood (2002–2006), given the accidental death, in the pilot episode, of the Jewish wife of non-Jewish Dr. Andrew Brown (Treat Williams), who goes on to raise their Jewish-identifying children, Ephram and Delia (Gregory Smith and Vivien Cadrone).

Aside from providing a ready subject for domestic conflict (as Larry David cited as justification for his “fake” TV intermarriage), television intermarriages sometimes constituted an autobiographical exercise. Jewish male predominance behind the scenes clearly played a role in the gender imbalance of interfaith romance on screen, as did many of these showrunners’, directors’, and writers’ indulgence in the practice. Moreover, dramas of marriage between a Jew and a non-Jew also became emblematic of intermarriage (religious, ethnic, class, regional, etc.) in general. Indeed, by using the family unit as a symbolic setting in which to investigate Jewish integration into American culture, such shows served as case studies of the overall challenge of cultural integration.

The intermarriage scenario writ large also reflected a concern by the networks (and showrunners) that an entirely Jewish family would be of limited interest to an American mass audience. After the original The Goldbergs and Rhoda, no other all-Jewish family identified as such would appear at the center of a prime-time series until the Silvers of Brooklyn Bridge, and even this exception was qualified by the show’s nostalgic, 1950s-period setting. Arrested Development, which appeared on the counter-programming Fox network in the early 2000s (later revived on Netflix), ended the Jewish family hiatus and broke the warm, cuddly mold. Indeed, the hyper-dysfunctional Bluth family, along with the nebbishy obnoxious Larry David and his agent’s loud-mouthed wife Susie Greene (Susie Essman) on Curb Your Enthusiasm, though no doubt viewed as “bad for the Jews” by many coreligionists, also indicated that Jews felt confident enough in American society to portray themselves in a decidedly unfavorable light.

Non-Episodic Television

While the most common appearances of Jewish women in American television figure in sitcoms, dramedies, or serious dramas about contemporary family life, the medium has also offered a wider range of portraits of Jewish womanhood in other programming genres. Of particular interest are episodes of ecumenical series from the late 1940s to the early 1980s, produced in conjunction with the Jewish Theological Seminary (Frontiers of Faith, 1951–1970; Lamp unto My Feet, 1948–1979; The Eternal Light, 1944–1989; Directions, 1960–1984) or other mainstream Jewish religious institutions. These public service series have occasionally presented dramas based on the lives of women such as Henrietta Szold, Emma Lazarus, and Jessy Judah, one of the first Jewish settlers of the New World; performances by the likes of choreographer Pearl Lang and folksinger Martha Schlamme; and interviews with American Jewish women ranging from opera singer Roberta Peters to Sally Priesand, the first woman ordained by the Reform rabbinate.

Occasional prime-time dramatic specials have dealt with the lives of Jewish women, both historical (A Woman Called Golda, a 1985 miniseries starring Ingrid Bergman as Israeli prime minister Golda Meir) and fictitious (Evergreen, a 1985 miniseries based on a popular novel by Belva Plain, which follows Anna, played by Leslie Ann Warren, a Polish Jewish immigrant to the United States, from the 1900s to the 1960s). The mini-series Angels in America (2003), based on Tony Kushner’s epic play, combined fiction and nonfiction in the ghostly figure of the executed Ethel Rosenberg (Meryl Streep) appearing, at his hospital deathbed, to the AIDS-stricken Roy Cohn (Al Pacino). As is true of presentations of Jews in general, American television has devoted more broadcasts to the experiences of Jewish women during the Holocaust than in any other historical period. Among the earliest of these was the appearance of Hannah Block Kohner, a survivor of four Nazi concentration camps, on a 1953 episode of This Is Your Life. The blockbuster mini-series Holocaust (1978, featuring Tovah Feldshuh) unleashed a decade-long mini-series and made-for-TV-movie obsession with the topic. Female Holocaust survivors have been the subject of documentaries (such as One Survivor Remembers, a portrait of Gerda Weissmann Klein, made by HBO in conjunction with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1995) and dramatic specials (such as Playing for Time,1980, which created considerable controversy when Vanessa Redgrave, known for her anti-Zionist activism, was cast as Auschwitz survivor Fania Fénelon, and, Miss Rose White, 1992, based on Barbara Lebow’s play A Shayna Maidel). Gina Sloan, an Italian Jewish survivor of the Holocaust and widow of an American GI, appeared as a regular character on the dramatic series Homefront (1991–1993), set in a midwestern small town in the late 1940s.

Anne Frank has been the subject of numerous documentaries and dramas on American television—more than any other Jewish woman. The earliest of these was a half-hour play by Morton Wishengrad presented in 1952 on Frontiers of Faith, followed by made-for-television versions of Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett’s authorized stage version of The Diary of Anne Frank in 1967 (starring Diane Davila as Anne) and 1980 (with Melissa Gilbert in the title role), and The Attic, a 1988 television movie based on the memoirs of Miep Gies, the Dutch woman who hid the Frank family. The diarist even survives the war in Philip Roth’s novella The Ghost Writer, adapted for television by American Playhouse in 1984, which explores her iconic stature in American Jewish culture.

Since the mid-1970s, a growing number of Jewish women have become documentary filmmakers, many of them presenting their work on public television, which has become the main venue for this genre in America. These women have made documentaries dealing with a wide array of subjects, including those of special interest to Jews and women (for example, Gina Blumenfeld’s In Dark Places: Remembering the Holocaust, 1978; and Lynne Littman’s In Her Own Time, a portrait of anthropologist Barbara Myerhoff, 1985). A number of Jewish women video artists (including Eleanor Antin, Beryl Korot, and Ilene Segalove) have used American TV as a point of departure in their work. The Jewish Museum in New York facilitated these artists’ television exposure, and the museum’s National Jewish Archive of Broadcasting houses many other examples of Jewish women in American television.

Morning Star Rising

The cable and streaming revolutions of the 1990s and 2010s, with their narrowcasting and niche-audience business models, not to mention less stringent or non-existent Federal Communication Commission (FCC) censorship, have encouraged ever more complex, multi-dimensional depictions of Jewish families, including Jewish mothers, in episodic television. Amazon Prime’s heavily Jewish-inflected Transparent, the first episodic series centered on a transgender character (Jeffrey Tambor’s patriarch-to-co-matriarch Maura Pfefferman) also competed with Arrested Development in family dysfunction. In Transparent, the negative aspect is tempered by the characters’ honest struggles for self-realization, and a similar juggling of pro and con characterizes Amazon’s The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, in which Miriam’s subversion of the feminine mystique and pursuit of a stand-up career clashes with the responsibilities of motherhood.

Besides the medium’s structural changes, an exponential increase in the 2000s in Jewish women’s involvement with production at all levels has contributed immeasurably to changes in women’s representation. Both Transparent and The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel were created by women, Jill Soloway and Amy Sherman-Palladino, respectively, as was Russian Doll (Netflix, 2019) created by Natasha Lyonne and Amy Poehler. The Showtime series Weeds (2005–2012) and Netflix series Orange is the New Black (2013–), though dealing only marginally with Jewish women, were created by Jewish showrunner Jenji Kohan. Sarah Silverman and Amy Schumer doubled as creative producers and stars in their shows, as have Lena Dunham in HBO’s Girls, Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer in Neflix’s Broad City, and Rachel Bloom in the CW’s Crazy Ex-Girlfriends. Not coincidentally, all these women-created shows have broadened the scope of Jewish women’s sexuality (and women’s sexuality in general) on television.

Much of the credit for women’s burgeoning presence behind the scenes and more variegated representation on-screen must go to a resuscitated, third-wave feminism generally and a targeted media monitoring group that emerged from it. Founded in 1997 by Jewish female and male industry professionals under the auspices of Hadassah (The Jewish Women’s Zionist Organization, Inc.), the Morning Star Commission took its name from Herman Wouk’s 1957 novel Marjorie Morningstar, purported to have popularized the Jewish Princess stereotype, and from a desire, in Morning Star director Mara Fein’s words, to create “a new morning in the representation of Jewish women—a morning star rising.” As of this writing, the star continues to rise.

Antler, Joyce, ed. Talking Back: Images of Jewish Women in American Popular Culture. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 1998.

Antler, Joyce. You Never Call! You Never Write! A History of the Jewish Mother. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Brook, Vincent. Something Ain’t Kosher Here: The Rise of the “Jewish” Sitcom. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003.

Fox, Stuart, comp. Jewish Films in the United States: A Comprehensive Survey and Descriptive Filmography. 1976.

Jewish Museum of New York. National Jewish Archive of Broadcasting: Catalog of Holdings. 2d ed. New York: The Jewish Museum,1995.

MacNeil, Alex. Total Television. New York: Penguin Books, 1991.

Moss, Joshua Louis. Why Harry Met Sally: Subversive Jewishness, Anglo-Christian Power, and the Rhetoric of Modern Love. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2017.

Stratton, Jon. Coming Out Jewish: Constructing Ambivalent Identities. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Zurawik, David. The Jews of Prime Time. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2003.