Tannaitic Literature, Inclusion of Women

Midrashic reading of verses often involves the question of whether or not women were included in the verses. The language used (structure of verbs, prepositions, other parts of speech) often indicates the particular interpreter’s opinions concerning women. Generally speaking, the more regular the mechanism of inclusive interpretation, the clearer it is that woman remains outside as the “other” because she requires a special reason to be included. In other words, rather than rendering women an integral part of the population, inclusion renders them as adjuncts, unique unto themselves.

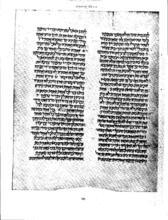

“If only A is mentioned, how does the verse in question apply to B?” is a Lit. (from Aramaic teni) "to hand down orally," "study," "teach." A scholar quoted in the Mishnah or of the Mishnaic era, i.e., during the first two centuries of the Common Era. In the chain of tradition, they were followed by the amora'im.tannaitic midrashic way of reading verses that occurs hundreds of times in midreshei The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah (halakhic A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash). It is rare in the Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah and (Aramaic) A work containing a collection of tanna'itic beraitot, organized into a series of tractates each of which parallels a tractate of the Mishnah.Tosefta and in the Lit. (Aramaic) "spokesman." Scholars active during the period from the completion of the Mishnah (c. 200 C.E.) until the completion of the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds (end of the fourth and fifth centuries respectively), who were active primarily in the interpretation of the Mishnah. In the chain of tradition they follow the tanna'im and precede the savora'im.amoraic sources. It is based on an assumption of exclusion, “Only A is mentioned so the verse applies only to A,” which in most cases also contains a corollary: “So how do we derive that it also applies to B?”: “Scripture goes on to say. …”

Examples

The matter of women’s inclusion occurs in this type of Midrash about sixty-five times: One example is the verse “You shall be holy people to me” (Exodus 22:30). “The text says ‘anshei,’ denoting men; how do we know it applies to women as well? Scripture goes on to say: ‘You shall be to me’” (Mekhilta Rashbi on Exodus 22:30). As a matter of fact, the question of women’s inclusion comes up in various areas: regarding kinds of work forbidden on the Sabbath, idolatry, sacrifices and the priestly blessing: “Thus shall you bless the people (men) of Israel” (Numbers 6:24–26), “The text mentions only a blessing for the people (men) of Israel, so how do we derive that it includes converts, women and slaves? Scripture goes on to say (v. 27): ‘And I will bless them’” (Sifri on Numbers 39); in the fields of justice, law, charity and torts, as ones who both incur and suffer damage (Leviticus 25:14): “‘Do not wrong one another’ [lit. ‘Let no man wrong his brother’]—only men are mentioned, so how can we include women in the premise?? Scripture goes on to say: ‘His brother’ in any case” [Sifri, Parashat Be-Har, 3, 9]). This is also the case regarding the inclusion of women in historic events such as the giving of the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah at Mount Sinai, as well as events to occur in the future.

Basis for Inclusion

The homiletic interpretation contains two sections. The first assumes an exclusion while the second rejects the exclusion, deriving and demonstrating inclusion. The most common basis for exclusion is based on various constructs of the Hebrew word for “man”—ish, anashim, anshei—though it can also involve words such as Yisrael, bnei Yisrael (children [lit. “sons”] of Israel), ben (son), aviha (her father), and so on. It appears that the interpreter is responding to certain words in the Scriptural text before him, and that the exclusion has a basis in the text.

But several unique expressions of exclusion show the formation of the interpreter’s awareness and his interpretive choice, especially when the word ish or any similar words do not appear in the verse in question, meaning that the verse itself contains no basis for the exclusion. In such cases, the basis is usually the interpreter’s own views regarding women, the society in which he lives, or an occurrence he is trying to prevent. The social and cultural implications are also reflected in the interpreter’s decision to exclude in such a way that the interpretation indicates the interpreter’s basic premise regarding various issues about which he speaks—women’s place in the sacred, women’s place in law and justice, and so on.

The basis for inclusion, too, has several clear characteristics that serve the interpreter in his inclusive reading of the text: conjunctive letters and prepositions such as “in,” “and,” “if” and et (which denotes a direct object), alliteration and verbs—even in the masculine—are used mostly to include women as active participants, unlike nouns, which mostly form the basis for including women as passive onlookers. Similarly, various other expressions leave women as “other” in the internal social structure: e.g., nefesh/nefashot (“individual”) and mutual expressions such as elav (to him), ahiv (his brother) and zar’o (his descendants), together with unique occurrences in Scripture such as verbs ending in the suffix –un (e.g., tehiyun and ta’anun), or a generalization based on Divine nearness or involvement in the topic in question.

Generally speaking, the more regular the mechanism of inclusive interpretation, the clearer it is that woman remains outside as the “other” because she requires a special reason to be included. In other words, rather than rendering women an integral part of the population, inclusion renders them as adjuncts, unique unto themselves.

One should also note that in most cases a parallel exists between the midrash’s halakhic conclusions and tannaitic halakhah (in the Mishnah and elsewhere) and therefore it is possible that halakhah, and not only the way in which the verses are read, determines the interpretation. This reinforces the impression that the interpretation we have constitutes the deliberate imposition of a given mind-set upon Scripture, not a mere innocent reading of it.