Teresa Sterne

Tracey Rosenbaum made her professional debut as the solo pianist Teresa Sterne at the age of twelve, but was forced by financial limitations to give up her budding career. She applied her musical talents instead to the recording industry, becoming the first woman in America to guide the destinies of a prominent record label.

Institution: London Times / Nonesuch Records

Teresa Sterne had two great careers in music, first as a child prodigy pianist, then as one of the first women record producers in the United States. Sterne debuted as a soloist with the NBC Symphony Orchestra at age twelve; a year later she performed with the New York Philharmonic. Her early career was successful, but she left music to support her family as a secretary and model. After a few years at Hurok Records and Columbia Records, she became director of Nonesuch Records in 1965, making the label a force in modern and classical music. She launched the Explorer Series and created important recordings of lesser-known composers. When she was diagnosed with ALS, friends in the music industry issued a two-disc set in her honor.

Early Life and Piano Career

While Teresa Sterne was vastly respected for her far-reaching service to music as a record company executive, few who knew her in that role were aware of her earlier career as a pianist, which was short-lived but stunning.

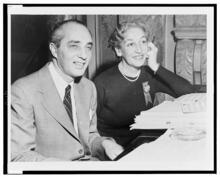

Sterne was born in Brooklyn, New York, on March 29, 1927, the only child of Bernard Rosenbaum, a violinist, and his wife Mary, a cellist. She showed exceptional gifts at an early age, and was taken out of school at age ten to be tutored privately while concentrating on the piano. Her mother, who gave up her own career to oversee her training, apparently decided that her own maiden name, Sterne, which she herself used professionally, would be a more suitable stage name than Rosenbaum for her daughter as well. Tracey began performing as Teresa Sterne at age eleven and made her professional debut at twelve as soloist in the Grieg Concerto with the NBC Symphony Orchestra; her New York Philharmonic debut came the following year, at Lewisohn Stadium. Her father left the family when she was fourteen, and her uncle, Robert Sterne, a violinist who had played in the Philharmonic, stepped in to assist with the development of her career. One of her teachers was the famous pianist Simon Barere; she received encouragement from such conductors as Dmitri Mitropoulos, Fritz Reiner and Leopold Stokowski. The Dutch-born composer and conductor David Broekman, who became an influential figure in her life, composed a sonata for her.

Music Production Career

In her early twenties, with the family’s resources strained to the limit, she set her career aside to work as a secretary and fashion model, thinking the income would enable her to pursue further studies and acquaint herself with the realities of a performer’s world. When she returned to music, however, it was not as a pianist, but as an employee of the Hurok organization, promoting the careers of other young musicians. Eventually she found herself in the recording industry, first in the custom department of Columbia Records (today’s Sony Classical), and then for seven years as secretary and general assistant to Seymour Solomon at Vanguard. In 1965 she began her historic association with Nonesuch, the classical “budget” label created only a year earlier as part of Jac Holzman’s pop- and folk-oriented Elektra Records. Holzman gave her more or less free rein, and she proceeded to turn it into a force that had a remarkable impact on the entire industry and the broader musical public.

As the first woman in America to guide the destinies of a prominent record label, Sterne (known to everyone as Tracey) set about redefining Nonesuch as an enterprise of enormous adventurousness, marked at the same time by unfailing taste and discernment. She transformed what had been a modest outlet for material leased from European companies into a major factor in her country’s musical life. She discovered and/or encouraged such composers as Charles Wuorinen, George Rochberg, Elliott Carter, William Bolcom and George Crumb, and such performers as the mezzo-soprano Jan DeGaetani, the pianists Paul Jacobs and Gilbert Kalish, Alex Blachly’s early-music group Pomerium Musicum, and Arthur Weisberg’s Contemporary Chamber Ensemble. She commissioned works especially for recording; with the pianist/musicologist Joshua Rifkin she launched the rediscovery of Scott Joplin; with the imaginative producer David Lewiston she created the Explorer Series of on-site recordings from the far corners of the earth; and with Bolcom (as pianist) and his wife, the mezzo Joan Morris, she began a still continuing series exploring the classics and forgotten treasures of American Popular Song. (She made one recording herself, as fifth hand in Ravel’s Frontispice with Jacobs and Kalish.)

Her ears were always open to new artists and new repertory, and her selectivity in choosing mastering technicians, pressing plants, annotators and illustrators served the music on an exceptional level. The musical community reacted with stunned disbelief when the new owners of Nonesuch dismissed her in December 1979. Protests went out from respected composers, performers and critics; concerts and other tributes were organized, and it was assumed that she would quickly land a more exalted position—but she never did

End of Life and Legacy

Just before her seventy-third birthday Sterne was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, known in America as “Lou Gehrig’s disease,” after the popular baseball player who was its first famous victim. ALS is a progressive deterioration of the motor nerves, virtually untreatable and invariably fatal. Friends rallied to her side, but could do little. Robert Hurwitz, her latter-day successor at Nonesuch, acting on a suggestion from Gilbert Kalish and Sterne’s devoted friend Norma Hurlburt, issued a set of two CD’s in Tracey’s honor: one disc made up of her own performances from her abortive career as pianist, the other of material chosen by her from among the numerous significant recordings she had brought into being.

The documentation includes tributes from several friends and associates. Two months after the set was issued, its context was changed to that of a memorial. Tracey Sterne died in her Manhattan apartment on December 10, 2000; a memorial concert, organized by Kalish and Hurlburt, was held at Symphony Space on May 29, 2001, her birthday.

Anderson, William. “Culture Management.” Stereo Review, April 1980.

Davis, Peter G. “The Special Touch of Nonesuch.” The New York Times, April 22, 1979.

Idem. “Classical Records: The Sounds of Crisis.” The New York Times, January 13, 1980.

Dyer, Richard M. “Fear and Loathing in the Record World.” Boston Globe, December 22, 1979.

Goodfriend, James. “A Canticle for Nonesuch.” Stereo Review, March 1980.

Porter, Andrew. “Musical Events.” The New Yorker, January 14, 1980.

Tommasini, Anthony. “A Scene-Stealer behind the Scenes.” The New York Times, July 31, 2000.

Idem. “Teresa Sterne, 73, Pioneer in Making Classical Recordings, Dies.” The New York Times, December 12, 2000.

The Nonesuch tribute set has a substantial booklet which contains the following: Bolcom, William. “An Incalculable Debt”; Crumb, George. “The Meaning of Nonesuch”; Freed, Richard. “Dedicated Virtuosity” [a biographical sketch]; Kalish, Gilbert, “A Musical Oasis”; Hurwitz, Robert, “Tracey and Me”; Lewiston, David. “Not as a Curiosity”; Sterne, Tracey. “Acknowledgements.”

The 2-CD set, “Teresa Sterne: A Portrait,” is Nonesuch 79619-2, issued October 10, 2000.