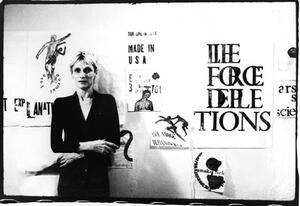

Nancy Spero

Rejecting postwar trends towards Pop art and abstract impressionism, figurative artist Nancy Spero earned a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1949 and spent a year studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In 1951 she married fellow artist Leon Golub. Spero created the Codex Artaud, scrolls blending text with images from Egyptian, Roman, and Celtic sources. Dedicating herself to the ideals of women as both artists and protagonists in art, she co-founded the AIR (Artists in Residence) Gallery in 1972, the first cooperative gallery of women artists. In 1995, Spiro and Golub were jointly awarded the Hiroshima Art Prize. Spero also created a mosaic for the Lincoln Center subway station called “Artemis, Acrobats, Divas, and Dancers.”

Nancy Spero was a figurative artist concerned with difference and the representation of the body. Her art, she told us, “speculates on a sense of possibility and comments upon immediate events, political, sexual and otherwise.”

Early Life and Family

Nancy Spero was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on August 24, 1926 to parents who were both born in the United States—Henry Spero (1898–1979, Cleveland) and Sadie Susselman (1903–1989, Scranton, Pennsylvania). Her father had a business buying and selling printing presses and her mother helped with the business later in her life. She had one sister, Carol Newman (b. 1928). Spero attended the University of Colorado, Boulder (1944–1945), received a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (1949), and studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and Atelier André L’Hote in Paris (1949–1950). In 1951, she married the visual artist Leon Golub (b. 1922-2004) and returned to Chicago. From 1959 to 1964, Spero and Golub lived in Paris. They had three sons: Stephen (b. 1953), Philip (b. 1954), and Paul (b. 1961).

Spero’s rejection of the dominant post-war movements of formalist Abstraction and Pop art, as promoted in the New York art world, stemmed from her formative years in Chicago where she was trained in the figurative tradition, her interest in the Art Brut championed by Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) whom she heard speak at the Art Institute, and her fascination with the ethnographic objects in The Field Museum, especially totems from Alaska and objects from New Guinea and the New Hebrides.

Artistic Work in the 1960s and 1970s

During the 1960s Spero’s art was in transition: she painted the oil series The Paris Black Paintings: Lovers, Prostitutes, Mothers and Children, Monsters (1959–1966); did small-scale gouache drawings and paintings for the Vietnam War Series (1966–1970); and used collage, cut-outs and text on paper (The Artaud Paintings, 1969–1970). She had a longstanding interest in the contrast of body types, the juxtaposition of images past and present, and varied historical references from different cultures.

In the 1970s, Spero often incorporated language into her work, using a variety of sources. Codex Artaud, a series of some 33 different scrolls produced from 1971–1972, represents Spero’s very first use of text as well as image. Codex Artaud quotes Egyptian, Roman, and Celtic images; it contains imaginary mirror portraits of Leonardo da Vinci along with images signifying Spero’s earlier work; the Artaud texts, typed in the original French and arranged to resemble concrete poetry, date from the early 1920s through 1948, articulating the poet’s extreme physical and mental anguish. The image of the tongue—body part and symbolic system—that Spero extracts from Artaud’s writings becomes the focus of the Codex Artaud.

After Antonin Artaud (1896–1948), Spero wanted to investigate the palpable realities of torture and pain (Torture of Women, 1974–1976) and to address explicitly the women’s issues in which she was involved. She joined WAR (Women Artists in Revolution), a radical group of women artists who split off from AWC (Art Workers Coalition), and co-founded AIR (Artists in Residence, Inc.), the first cooperative gallery of women artists in the United States, with five other female artists, Barbara Zucker, Dottie Attie (b. 1938), Susan Williams, Mary Grigoriadis, and Maude Boltz. AIR Gallery opened in New York City in September 1972 with a group show of its founding members.

Later Career, Awards, and Legacy

Throughout the 1980s, Spero continued her commitment to the woman as protagonist in her artwork: she exhibited To The Revolution (1981–1983), Sky Goddess (1986), Fleeing Woman/Irradiated (1986), and Sheela and the Dildo Dancer (1987). To The Revolution, after dance by Isadora Duncan, was the cover art for Shifting Scenes: Interviews on Women, Writing and Politics in Post-68 France, edited by Alice A. Jardine and Anne M. Menke (Columbia UP, 1991).

In 1993 Spero, among a number of artists, was invited to make an installation for the opening of the renovated Jewish Museum in New York. Spero’s The Ballad of Marie Sanders/Voices: Jewish Women in Time, a text and image installation of a Brecht poem, a poem by the Nobel Prize-winning Jewish poet, Nelly Sachs, “That the Persecuted May Not Become the Persecutors,” and a phrase from “Death Camp,” by the contemporary Jewish poet Irene Klepfisz, interspersed with fragmented photo-images documenting Jewish women in history.

In 1994, the MIT List Visual Arts Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, organized an exhibition called Leon Golub and Nancy Spero: War and Memory, which traveled to the American Center in Paris. And in 1995, Nancy Spero and Leon Golub were jointly awarded the third Hiroshima Art Prize and retrospective exhibition.

Nancy Spero’s work is found in the permanent collections of museums throughout the world, including The Museum of Modern Art (New York), The Tate Gallery (London), and Uffizi Gallery (Florence). “Artemis, Acrobats, Divas, and Dancers,” a permanent mosaic commissioned by Arts for Transit, is at the 66th Street/Lincoln Center Subway Station, New York City.

A.I.R. Gallery (http://www.airnyc.org/history.cfm); Bird, Jon, Jo Anna Isaak, and Sylvère Lotringer. Nancy Spero. London: 1996

Blocker, Jane. What the body cost: desire, history, and performance. U of Minnesota Press, 2004..

De Julio, Maryann. “Nancy Spero’s Codex Artaud.” Dalhousie French Studies 39/40 (1997): 137–140.

Lyon, Christopher. Nancy Spero: the work. New York: Prestel, 2010.

National Foundation for Jewish Culture (http://www.jewishculture.org/docs/awards-arts-spero.html).

Robins, Corinne. "Nancy Spero:“Political” Artist of Poetry and the Nightmare." Feminist Art Journal 4, no. 1 (1975): 19-23.

Spero, Nancy, Jon Bird, Jo Anna Isaak, and Sylvère Lotringer. "Nancy Spero." ICA, 1987.

Spero, Nancy, and Deborah Frizzell. "Nancy Spero’s War Maypole/Take No Prisoners." Cultural Politics 5, no. 1 (2009): 118-132.

Turner, Jane, ed. The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 29. New York: 1996.

Withers, Josephine. "Nancy Spero's American-born Sheela-na-Gig." Feminist Studies 17, no. 1 (1991): 51.