Mirali Sharon

Mirali Sharon belongs to the first generation of native Israeli choreographers who sought to create contemporary dance with a uniquely Israeli character. She collaborated with her fellow artists in the music, literary, architectural and plastic arts to choreograph dances with a vibrant Israeli quality shining through contemporary influences.

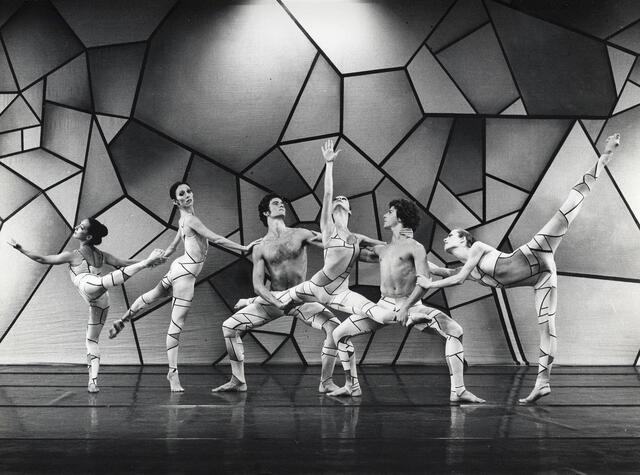

Courtesy of Mirali Sharon, Tel Aviv

Mirali Sharon was one of Israel’s most important choreographers in the 1970s and 1980s. Her work is characterized by organic integration of music, costume, and décor, with dance being the outcome of the composer-designer-scenarist-choreographer composite as one fertile, creative team. She danced with Gertrud Kraus’ Israel Ballet (1951) and Noa Eshkol’s Chamber Dance Groupe (1954). After studying in the United States with Merce Cunningham and Alvin Nikolais, she returned to Israel, bringing with her new ideas of avant-garde post-modern dance and creating several works for Batsheva and Bat-Dor dance companies. Known first as a choreographer for mainstream companies, she later shifted towards the Independent choreographers and founded her own company in 1983.

“All her work is characterized by organic integration of music, costume and décor, with the dance being the outcome of an approach to the composer-designer-scenarist-choreographer composite perceived as one fertile, creative team. Another feature of her work is the decidedly vibrant Israeli quality shining through a tissue of otherwise contemporary influences.” (“New Directions in Dance,” Ariel, 1976)

Mirali Sharon, whose work has been performed in Israel and at prestigious festivals abroad, is one of Israel’s major choreographers of the 1970s and 1980s. She belongs to the first generation of native Israeli choreographers who sought to create contemporary dance with an Israeli character, collaborating with contemporary Israeli artists in music, literature, architecture, and the plastic arts.

Family & Dance on the Kibbutz

Sharon was born on October 11, 1931, on Kibbutz En-Harod, the daughter of two of the kibbutz’s founders. Her father, Eliezer Ben-Ezra (1902–1955), was a university graduate and a musician who immigrated to Palestine from Russia in 1920. A man of great enterprise, he established the insurance fund of the agricultural settlements and also initiated an air company for spraying insecticides. In 1923 he married Sara (née Chen, b. Russia 1900, d. 1974), also a university graduate, who had immigrated from Kharkov (Ukraine) in the same year he did and whose work in agriculture on the kibbutz included managing the orchards. In addition to Mirali, the couple had two other daughters: Nira (Chen), a musician, born in 1924, and Noa (Chaikin), who was born in 1926 and died in 2002.

From childhood on, Sharon participated through choreographing and dancing in all the dance events that were customary on the kibbutz at the time, as part of the festival pageants that sought to give new expression to Jewish holidays. Sharon grew up on the prevalent belief that Israelis would be restricted if they did not create a culture and language of movement for themselves. She was connected to the movement for creating Israeli folk dances, choreographed by Rivka Sturman, like herself a member of Kibbutz Ein-Harod. Sharon was a member of the folk-dance delegation to the Jewish Youth Festival in Prague in 1947 and in Budapest in 1950.

Leaving the Kibbutz

At the beginning of the 1950s Sharon left the kibbutz and joined the Israel Ballet Theatre founded by Gertrud Kraus, where she danced in Talley Beatty’s “Fire in the Hills” (1952). At the same time, she studied with Tehilla Rössler, one of the important teachers of expressionist dance (Ausdruckstanz), who was renowned for her method. She developed a special connection with Noa Eshkol, who invented the Eshkol-Wachman dance notation system. She was also a dancer in the Movement Quartet.

In 1953 Mirali married Uzi Sharon (b. 1928), a physicist specializing in laser technologies and missiles, who developed a medical laser for general surgery that bears his name (Sharplan). Their daughter Maya (Wolf) was born in 1969.

Dance Career Develops

Soon after leaving Ein-Harod, Sharon opened her own dance studio and directed movement for performances by the Ohel Theater (1954), for Lorca’s Yerma at the Cameri Theatre (1957), and for the Theater Quartet, Nissim Nativ’s Actors’ Studio, army groups, and festivals on agricultural settlements.

In 1958 Sharon traveled to the United States. Unlike most Israeli women dancers, who went there to study with Martha Graham or at Juilliard, Sharon searched for tools to create her own language of movement and therefore studied with Alwin Nikolais, Murray Louis, and Merce Cunningham. The Israeli Consulate in New York sent her solo performance on tour throughout the United States and Canada. She returned to Israel in 1960 and in 1963 she again went to the United States, where she appeared in the dance companies of Nikolais and Murray Louis. In 1967, she founded her own company, receiving excellent reviews.

Reputation spreads

Sharon returned to Israel in 1970, bringing with her the new ideas of avant-garde post-modern dance, but she discovered that Israel’s leading companies had no appropriate framework for her experimental work. Neither the Batsheva nor the Bat-Dor companies found her daringly anti-establishment ideas acceptable and Israel had no “fringe” dance until 1977. Ultimately, however, the Batsheva and Bat-Dor companies, which normally doubted the capabilities of Israeli choreographers who had not been members, allowed Sharon to work with them because of the favorable reviews she had earned abroad. For Batsheva, she choreographed Transitions (1971), a duet with an arch that served as a bridge around which a human conflict and union occurs, and Lyric Episodes (1972), to music commissioned from Zvi Avni, using Uzi Sharon’s set consisting of four colorful panels, opening like the pages of a book. Following the Yom Kippur War Sharon made Taltala (“Shaking,” 1973), about the blow to the Israeli self-confidence, and Monodrama (1975), a monologue by a woman in various emotional states.

In 1978, Paul Sanasardo was named artistic director of Batsheva. He canceled the company’s previous contracts and did not agree to renew rehearsals on a piece Sharon was in the midst of choreographing. With Batsheva now closed to her, Sharon began to choreograph for Bat-Dor. For Bat-Dor, she choreographed Prisme (1976), He and She (1976), Leda (1978), Hymn to Jerusalem (1978), The Dreamer (1979), and Opus 5 (1981), known for their contemporary look. Prism (1976) was an ensemble dance to music by Marc Kopytman, an immigrant from the then USSR, and with a set by David Sharir. The dance was in seven segments dealing with human conditions passing through various prisms, each evoking memories. Sharon’s Anthem for Jerusalem was created in 1980 for Bat-Dor. The music was from Mordecai Seter’s Jerusalem Symphony, set and costumes by Sharir. The dance dealt with both the keening over the destruction of Jerusalem and the joy at its redemption.

In 1977, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat made his historic visit to Jerusalem and in 1979 a peace treaty was signed between Israel and Egypt. In that same optimistic year, an international convention on the subject of dance in the bible took place. The brainchild of Giora Manor, the week-long convention was part of the Israel Festival. To honor the event, Bat-Dor mounted the world premiere of Sharon’s Master of Dreams, based on the story of Joseph and his brothers that fit perfectly with the renewal of relationships with Egypt.

Jeanette Ordman, the Artistic Director of Bat-Dor, was the inspiration for He and She (1976) to music by Zvi Avni and set by Sharir. It was based on Coppelia, the 1870 ballet by Saint Léon. Ordman danced the mechanical doll and Yehuda Maor the clockmaker. This is a dance with a mad humor about a kind of clockmaker-wizard who animates the doll – until the doll turns on her maker. The dance was a hit, and one of Ordman’s favorites.

The Mirali Sharon Company (1983-1986)

Known first as a choreographer for mainstream companies, Sharon later began to shift towards the Independent choreographers. In 1980, a delegation from the Pompidou Center in Paris came to Israel to watch performances by both large companies and independent ones, in order to engage dances for Israel Week at the noted avant-garde center. The delegation invited both Batsheva and the Kibbutz Dance Company and asked Sharon to prepare an evening of her own works. She assembled a group of dancers and created a new dance, Phoenix (1980), to a musical collage by Yossi Mar-Haim. The dance was inspired by the legend that the phoenix (or firebird’s) nest is consumed by fire every 1000 years, but the bird is resurrected. The dance, Sharon says, like the legend, is based on the idea of recurrence. Sharon explained: “Life grows from death. A new cycle rises from the ashes, life cycles of adventure and new experience.” Her success in Paris convinced Sharon that it was time to form her own company and join the Independents. Sharon formed her own company in 1983; in the same year she made Hymns to Jerusalem, which she described as an anthem to life. The dance was set to the music of Steve Reich, based on several chapters of Psalms. Other dances she created for her company were Reflexion (1983), La Folie (1984), and Tehillot (1985).

In addition to performing in Israel, Sharon’s company appeared in the United States, in Canada, and at the Pompidou Center in Paris. Dancers of the first rank, including Rina Schenfeld, Ohad Naharin, Shelly Shir, Nira Paz, Yair Vardi, David Dvir, and the late David Rappaport appeared in her works. For most of her works she commissioned leading Israeli avant-garde composers, including Zvi Avni, Joseph Tal, Mark Kopitman, Mordechai Seter, and Yossi Mar Haim. David Sharir, Uzi Sharon, Yigal Tumarkin, and Buki Schwartz created sets for her work.

According to Sharon, “I created and created. There were invitations for additional shows. It did seem as though the whole world was open to me and I could realize my life’s dream, but I received financial support only once, and little enough of it. … that heroic experience could not continue without support.” (cited in Eshel, Dance is a Unique Entity of Life) The company folded after only three years, and Sharon devoted her time to public activity in the field of dance.

Sharon also created movement for Habimah and other theater companies, as well as for the Israel Opera. Between 1980 and 1985 she represented Israel in the Conseil International de la Danse (CIDD). Sharon was many years a committee member of the Cultural Authority and lectured and trained teachers. In 2002 she received an award for lifetime achievement from the Israel Ministry of Science, Culture and Sport. She died after long illness in 2017 and was survived by her daughter Maya, born in 1969.

A conversation with Mirali Sharon, 2018 (Hebrew)

Doudai, Naomi. “New Direction in Dance.” Ariel, March 1976.

Dunning, Jennifer. “Mirali Sharon Troupe in US Debut.” New York Times, October 17, 1983.

Eshel, Ruth. Dancing with the Dream: The Beginning of Artistic Dance in Israel, 1920–1964. Tel Aviv: Sifriyat Hapoalim and the Dance Library of Israel, 1991. (Hebrew with English summary.) Available at https://www.israeldance-diaries.co.il/en/about/books/.

Eshel, Ruth. “Dance Conversation - Mirali Sharon.” Academic channel (University of Haifa), film, 56 minutes, 2001.

Eshel, Ruth. “Dance is a Unique Entity of Life.” Mahol Akhshav (Dance Today) 12, April 2005, pp: 20-26.

Eshel, Ruth, Dance Spreads its Wings: Israeli Concert Dance in Israel 1920-2000. Tel Aviv: Israeldance-Diaries.co.il, 2016, pp. 216-218, 231-232, 354-356.

Gluck, Rena and Lana, Iris. “A Conversation with Mirali Sharon,: Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3z3UCmSrJm4. Acceessed 242 August 2018.

Kisselgoff, Anna. “Dance by Batsheva.” The New York Times, May 12, 1972.