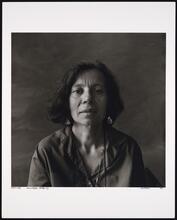

Yente Serdatsky

Proud, independent, enterprising, and contentious, Yente Serdatsky exemplifies the enormous difficulties experienced by Yiddish women writers in achieving recognition. Her long-neglected work has engaged the attention of contemporary Jewish feminist literary critics. Serdatsky's first story, “Mirl,” was published in Warsaw in 1905 in the journal Der Veg. In 1907, she immigrated to Chicago and ran a café where impoverished immigrant would-be writers could eat homemade meals. At the same time, she published stories, one-act plays, and dramatic sketches in various Yiddish periodicals, including the anarchist Fraye Arbeter Shtime, the socialist Fraye Gezelshaft, Fraynd, Di Tsukunft, and Avrom Reisin’s Dos Naye Land. Serdatsky’s fiction and dramatic works focus mainly on women like herself: European immigrants who believed in left-wing political movements.

Proud, independent, enterprising, and contentious, Yente Serdatsky exemplifies the enormous difficulties experienced by Yiddish women writers in achieving recognition. Her long-neglected work has consequently engaged the attention of contemporary Jewish feminist literary critics.

Early Life and Family

Serdatsky was born Yente Raybman on September 15, 1877, in Aleksat, near Kovne (Kaunas), c. Her scholarly father, Yehoshua, dealt in used furniture and provided his daughters with a basic Jewish education, including attendance at a Jewish girls’ school whose teachers were young men from a nearby yeshiva. At thirteen, she was apprenticed to a seamstress, then worked in a grocery store in Kovne and eventually owned her own grocery store there. She continued to read books in German, Hebrew, and Russian during those years.

In 1905, Serdatsky left her husband and three children and went to Warsaw to pursue a literary career. Her first story, “Mirl,” was published in 1905 in Der Veg [The way], a journal edited by Bal-Makhshoves. She was also encouraged by Y. L. Peretz, whose home was a gathering place for budding literary talent.

Work in America

In 1907, Serdatsky immigrated to America. At first she lived in Chicago, where, according to Moyshe Weissman, she ran a café where impoverished immigrant would-be writers could eat homemade meals. In New York, her eating place was described as a soup kitchen. At the same time, she published stories, one-act plays, and dramatic sketches in various Yiddish periodicals, including the anarchist Fraye Arbeter Shtime [Free voice of labor], the socialist Fraye Gezelshaft [Free society], Fraynd [Friend], Di Tsukunft [The future], and Avrom Reisin’s Dos Naye Land [The new land]. Her only published volume, Geklibene Shriftn [Selected works], including stories, novellas, and dramatic sketches, was published in 1913. She was on the staff of the influential Forverts and her work appeared regularly until 1922, when she quarreled over money matters with Abraham Cahan, the formidable editor of the paper. She was removed from the editorial staff and seems not to have published for over twenty-five years. Without income from her writing, she lived partly on welfare and partly from renting furnished rooms.

In 1949, Serdatsky began writing again, primarily in the Nyu Yorker Vokhnblat [New York weekly] to which she contributed some thirty stories and reminiscences of Y. L. Peretz. Shea Tenenbaum’s memoir of Serdatsky suggests that she was morbidly obsessed by Peretz throughout her career.

Legacy

Serdatsky’s fiction and dramatic works focus mainly on women like herself, immigrants who emerged from European, mainly Russian, left-wing political movements. These women, though committed to change and the future, frequently long for the traditional Jewish past they supposedly abandoned. They came to America seeking to build an ideal society together with like-minded male comrades. Instead, they face alienation and loneliness in a society that has little place for radical intellectual women. Serdatsky’s leading characters who are involved in liaisons are inevitably exploited by lovers and husbands. Nevertheless, her narratives abound in lonely women searching for love and faith. Most are doomed to disappointment. Serdatsky died on May 1, the workers’ holiday, in 1962, at age eighty-five.

Poet-critic Yankev Glatshteyn, writing shortly after Serdatsky’s death, acknowledged that her considerable talent had been largely unappreciated. He proposed an edition of her uncollected writings as a fitting memorial for Serdatsky, whom he characterized as an “angry” writer. While it conveys Serdatsky’s rage and faults her for wasting time shouting and protesting instead of quietly writing, critic Shea Tenenbaum’s memoir also portrays her commanding presence and her powerful, intense character.

Tenenbaum, Shea. Ayzik Ashmeday (1964).