Alice Lillie Seligsberg

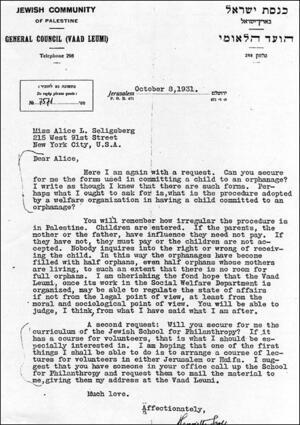

Courtesy of the Hadassah Archives at the American Jewish Historical Society.

A passionate social worker and Zionist, Alice Lillie Seligsberg devoted herself to underprivileged youth and to the Zionist movement. Although she is best known for her leadership in Hadassah, her work in social services led to historic changes in the field. She headed the Jewish Children’s Clearing Bureau for several years and established several organizations of her own, including a girls’ club on the Lower East Side. Seligsberg was also responsible for sending the first group of Hadassah nurses to Palestine. During her time in Palestine, she worked with orphaned children and victims of war. She returned to New York in 1920 and soon became the national president of Hadassah. Seligsberg was later a dedicated advisor to the Junior Hadassah Organization, spearheading several significant projects in Palestine.

Alice Lillie Seligsberg, an American Zionist, social worker, civic leader, and Hadassah president, gave herself to the orphaned and needy of her people, and influenced thousands of Jewish girls and women for more than a generation. It was in her love for Judaism, and by its extension, Zionism, that Seligsberg made her greatest contributions.

Early Life & Social Services Career

Seligsberg was born to Louis and Lillian (Wolff) Seligsberg on August 8, 1873. She had one sister and one brother, and the family lived in New York City. Among the first graduates of Barnard College, Seligsberg did graduate work at Columbia University and in Berlin, Germany. It was to poor and underprivileged children that Seligsberg gave her earliest energies. Beginning her career as a social worker and youth leader, she formed a girls’ club on the Lower East Side, where she had a great influence upon the members.

After serving as a club worker at the Hebrew Sheltering Guardian Society, Seligsberg established Fellowship House, an institution that placed poor and orphaned children in suitable homes and positions. She was its president from 1913 to 1918.

Seligsberg was responsible for many original contributions to the field of social services. For example, she recommended that the boarding-out department of the Hebrew Sheltering Guardian Society become independent of any institutional control, responsible only to the directors of the parent program. According to experts in the field, this idea completely changed the course of Jewish child care, not only in New York, but throughout the country as well. From 1922 until 1936, Seligsberg served as executive director of the Jewish Children’s Clearing Bureau, which placed children in homes and/or orphanages based on the needs of the individual child.

Jewish Life

As she grew older, Seligsberg realized that the Ethical Culture Movement, with which her family had been affiliated, did not offer her what she needed. She turned to Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan of the Society for the Advancement of Judaism for help in her return to Judaism. She began studying the Bible and the Prophets, Hebrew, and Jewish history. She also began lively correspondence with Rabbi Judah Magnes, Felix Adler, Henrietta Szold, and Jessie Sampter, among others. She discussed her philosophical ideas and perceptions about Judaism and its place in her life. According to Rose Jacobs, “She found in the wisdom of the Jewish sages and prophets something her soul had been seeking, and she identified herself completely with the Jewish community.” The culmination of this identification was in her work with Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America. In 1913, Seligsberg joined the original study group and thus began a lifelong association with Szold, Zionism, and Hadassah.

Work in Palestine

In 1917, Seligsberg helped with the organization of the first group of Hadassah nurses being sent to Palestine. By the time this group was ready to leave, in June of 1918, she was asked to take the place of E. W. Lewin-Epstein, its business administrator, who had suffered a heart attack.

After a year in Palestine, David de Sola Pool, of the American Joint Distribution Committee, asked Seligsberg to head the Orphans Committee, which was formed to aid Jewish victims of war. But her work in Palestine extended beyond her daily involvement with the Orphans Committee—she also served as a board member of the Institute for the Blind in Jerusalem. While in Palestine, Seligsberg also found time to write several articles and reports about Jewish orphans and other areas of social work in Palestine.

Return to New York

After returning to New York in 1920, Seligsberg immediately resumed her career in social work. In 1922, she was named executive director of the Jewish Children’s Clearing Board of New York, and, from 1921 to 1923, she served as the national president of Hadassah. Upon completion of her presidency, she became the Palestine advisor to the Junior Hadassah Organization, a position she held until shortly before her death. During her tenure as advisor, Junior Hadassah launched a number of significant projects in Palestine, including the revitalization of Meier Shefeyah, a Youth Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah village that housed many war orphans. In a letter to Junior Hadassah, she wrote of her vision for Hadassah and Palestine: “[W]e must say that we think of tasks not merely as medical enterprises or children’s services, but as educational projects in the highest sense for Palestine as a whole. … Our ultimate task—the Zionist hope—however, is the upbuilding of the Jewish Homeland as a socially just and creative community, creative in every domain, in science, in art, in religion, a community in which every person may develop to the utmost of his power.”

When Alice Lillie Seligsberg died on August 27, 1940, Hadassah immediately allocated $25,000 to build a memorial to her in Palestine. This memorial, dedicated by Henrietta Szold on October 15, 1940, established a clinic at the Children’s Village. The Alice L. Seligsberg Vocational High School for Girls, which later became the Seligsberg-Brandeis Community College, was also established as a lasting memorial.

AJYB, 43:364, 431–436.

EJ.

Obituary. New York Times, August 29, 1940, 19:1.

UJE.

WWIAJ(1926, 1928, 1938).