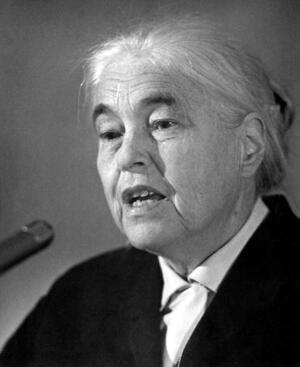

Anna Seghers

In 1928, Anna Seghers was awarded for her emerging writing talents and joined the Communist party in Germany. After the burning of the Reichstag in 1933, Seghers went into exile in France and became a leader in anti-fascist efforts. Her novels in exile analyzed the rise of fascism and brutality in Germany, including her most famous, Das siebte Kreuz (1942, The Seventh Cross), which became a bestseller and a Hollywood film starring Spencer Tracy. At the outbreak of World War II, she left Europe with her family, eventually settling in Mexico City. There she wrote her most enduring novel, Transit (1944), about the plight of refugees. Seghers returned to Berlin in 1947, received the International Stalin Peace Prize in Moscow in 1952, and remained, controversially, an icon of the GDR until her death.

Early Life

Anna Seghers, one of the most important German women writers of the twentieth century, was born Netty Reiling on November 19, 1900, in Mainz on the Rhine. On both her parents’ sides she came from Jewish families that had risen to prosperity during the nineteenth century. Her father, Isidor Reiling (1867–1940), was an antiquarian and art dealer whose store on the Flachsmarkt had national and international business connections. Her mother, Hedwig Fuld (1880–1942), belonged to a very wealthy Frankfurt family, which also dealt in art and antiquities but whose members branched out into other very successful enterprises at home and abroad. Isidor Reiling was a member of the Israelitische Religionsgemeinschaft in Mainz, the conservative branch of the Jewish community, and he and his young wife raised their daughter in the Orthodox faith. Netty, an only child, was often ill and sought solace in her vivid imagination and in books. Trips to the sea and to health spas were part of her early experience and fostered a lifelong love of travel and of the water. Besides the sea, rivers—as symbols of openness, freedom, and adventure—figure prominently in her stories and novels.

As she grew up and went to school, Netty Reiling had both Jewish and Christian friends and absorbed the Christian, mostly Catholic, atmosphere of her hometown, which was dominated by the cathedral of Mainz. Christian motifs and allusions play an important role in much of her work, and a Lutheran bible appears to be one of the most used books in her study in Adlershof near Berlin, where she lived for the last thirty years of her life and which is now a museum housing her large library. Still, as a young adult—and unlike many others at the time—she did not consider conversion an option. Instead she developed a strong interest in the existential Christianity of Sören Kierkegaard (1813–1855) as well as the writings of Martin Buber (1878–1965) and remained religious long after she had given up her father’s Orthodox faith. Only in 1932 did she and her husband officially leave the Jewish community. By then she had been a member of the German Communist Party for four years. During the rest of her life, she retained a profound respect for religion in general and in particular for her parents’ faith as well as for Christianity. She believed that Communism was to continue and complete the social mission of Judaism and Christianity.

University Studies and Writing Beginnings

Netty Reiling’s formative years coincided with World War I and the social upheavals and crises that followed. Although her own material existence was not greatly affected, she was deeply sensitive to the changes around her. Early on she became an opponent of the chauvinism prevalent on both sides of the Rhine and developed a love for France and its emancipatory traditions, which grew during her lifetime. From 1920 to 1924 she attended the University of Heidelberg, at the time still the most vibrant place of study in Germany. In her four years there she pursued many subjects, including Chinese language and culture, German, French, and Russian literature, sociology and history, ultimately obtaining a doctorate in art history. Her dissertation, on Jude und Judentum im Werke Rembrandts (Jews and Judaism in the Work of Rembrandt), showed her evolving interest in art and its relationship to social developments.

During her time in Heidelberg, Netty Reiling encountered Ladislaus Rádványi (1900–1978), her future husband. He was a Hungarian Jew and fellow student who had been a member of Georg Lukáçs’s “Sunday Circle” and had fled his home country after its Soviet-style government was overthrown by the Horthy regime in 1919. She married him in 1925 with her parents’ reluctant consent and followed him to Berlin. A member of the German Communist Party since 1925, he worked for the Marxistische Arbeiterschule (MASCH), an important and popular effort to bring political as well as general education to the working classes. The school drew upon the left-wing and increasingly communist intelligentsia of the Weimar Republic for its teachers, and Rádványi soon became its head. He remained a teacher all his life and was Seghers’s great love and most important advisor. The couple had two children: Pierre (b. 1926) and Ruth (b. 1928).

Seghers never practiced art history but retained a life-long interest in art, which influenced her theoretical and practical approaches to writing as well. She was a highly cultured, widely read person who especially loved Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, Kleist, Büchner and Kafka, Racine and Balzac, and was steeped in fairy tales and Jewish and Christian legends. She became serious about writing during her last year at university and in late 1924 published her first tale, “Die Toten auf der Insel Djal” (The Dead on the Island of Djal), which she subtitled “A legend from the Dutch, retold by Antje Seghers.” From then on she wrote steadily and honed her craft. Two stories from this early period, “Die Legende von der Reue des Bischofs Jehan d’Aigremont von St. Anne in Rouen” (The Legend of the Penitence of Bishop Jehan d’Aigremont of St. Anne in Rouen) and Jans muß sterben (Jans Must Die), were only recently discovered and published. Her next two publications were the story “Grubetsch” (1926) and the book-length Der Aufstand der Fischer von St. Barbara (1928, The Revolt of the Fishermen). Both appeared under the name Seghers—probably after the Dutch painter Hercules Seghers, a contemporary of Rembrandt—but originally without a first name. The author then chose Anna Seghers as her pen name and public persona and kept it for the rest of her life. The two stories with their hard-hitting, sparse language and expressive imagery won the author widespread attention: In 1928, she received the prestigious Kleist-Prize for newly emerging talents.

In that same year Seghers joined the Communist party and became a member of the BPRS, the Association of Proletarian Revolutionary Writers, which pronounced art to be a weapon in the class struggle. Seghers’s work had its roots in Expressionism. From the first it was anti-bourgeois in impulse and focused on outsiders, particularly the poor and disenfranchised. Now it became more political but did not lose its poetic qualities. Then and later it met with criticism for vagueness from the Party. This lack of real appreciation never affected Seghers’s commitment to “die Sache,” the socialist enterprise in general, and the Party in particular. To her mind, such commitment always involved sacrifice. At the same time and throughout her life she championed art and the necessary freedom of artistic expression—as much as she felt her loyalty to the Party would allow. It was a life-long balancing act that became much harder, even tragic, in later years, when she lived in the German Democratic Republic and became privately disillusioned with the path communism had taken. She always relied on her own art to show more than her public pronouncements did and repeatedly pleaded for attentive readers who would appreciate the many layers of her work.

In 1930 Seghers published a collection of stories, Auf dem Weg zur amerikanischen Botschaft (1933, On the Road to the American Embassy), in which she displayed the full range of her work and talent. Her first novel, Die Gefährten (The Companions), followed in 1932. It is an account of the international Communist movement after the Russian Revolution with emphasis on the fate of individuals and their sacrifices for the cause. Politically and stylistically it is her most avant-garde work, espousing an internationalism which had its (unacknowledged) roots in Trotsky and using techniques of writing pioneered by John Dos Passos (1896–1970) and Alfred Döblin (1878–1957).

Exile in France

When Hitler came to power in January 1933 Seghers did not immediately flee the country. However, after the burning of the Reichstag in February, she was briefly arrested and upon her release left immediately for Switzerland. Like so many other exiles, she then went on to France, where she and her family settled on the outskirts of Paris, in Bellevue. She became very active in building the Volksfront (Popular Front), an anti-fascist coalition that transcended party lines, although Moscow and the Communists played a leading role in it. Seghers was one of the organizers of the International Congress for the Defense of Culture, which was held in Paris in 1935 and brought together writers and intellectuals from thirty-eight countries. For her the years of exile in France were most productive. Besides her anti-fascist speeches, essays, and activities, which insisted on the existence of “the other Germany” and reclaimed its roots in the culture and traditions which the Nazis misappropriated, she wrote many novels and stories and produced some of her best work. She also critically reflected on what had enabled Hitler to come to power so easily.

In the major literary debates of the late thirties, the so-called “Expressionismus-Debatten” which were in fact discussions on realism, Seghers, like Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956), Ernst Bloch (1885–1977), and Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), defended modernist approaches to art and an open attitude towards different styles of writing against the conservative prescriptions coming from the Soviet Union and Georg Lukács (1885–1971), the Marxist critic. Her own fiction, however, never again returned to the experimental style of Die Gefährten. Rather, it turned to a more traditional form of the modern novel, advocated by Lukács, which was rooted in the great masters of the nineteenth century, Tolstoy and Balzac. Yet she never really adhered to the norms of “Socialist Realism” as they were being defined, even if critics tried to make her later work fit that category.

Seghers’s first novel to appear in exile was Der Kopflohn (1933, A Price on His Head), with the subtitle Roman aus einem deutschen Dorf im Spätsommer 1932 (Novel from a German Village in the Late Summer of 1932). It is a striking study of the rise of fascism and the brutality it causes among some of the farming population in Germany. One of Seghers’s themes here and elsewhere is the longing of young people without prospects for a sense of purpose and self-worth. Another is the fate of women under such circumstances.

After the 1934 Civil War in Austria, Seghers traveled through this country to research the events. They stirred anti-fascists everywhere because Austrian Social Democrats and communists had actually fought together against Dollfuß’s clerical-fascist regime, and had done so side by side. They had lost, but in Seghers’s presentations—a story, “Der letzte Weg des Koloman Wallisch” (Koloman Wallisch’s Last Road) and a novel, Der Weg durch den Februar (1935, The Path through February)—the defeat, as always, contains the promise of strengthened resolve and future, eventually successful, struggles. Her next novel, Die Rettung (1937, The Rescue), focused on Germany and the plight of the industrial working class at the end of the Weimar Republic.

Seghers’s last novel to be completed in French exile would become her most famous, Das siebte Kreuz (1942, The Seventh Cross). It offers a striking panorama of Germany under Hitler, specifically of her beloved Rhine region around Mainz, its Nazis, opportunists, and quiet, decent people. Despite pervasive fear, the latter manage to help one of seven fugitives from an early concentration camp to escape to freedom. Although Seghers worked intensively on her novel during the time of “Kristallnacht,” when her parents in Mainz, with whom she had stayed in close contact, were directly affected, she did not give special consideration to the worsening plight of Jews. This “blind spot” had to do with communist ideology in general and her own wish to speak for all those “other Germans” who did not make racial and ethnic distinctions. The novel and its success abroad as well as among Germans was predicated on its vision of the power of ordinary human beings to resist even the strongest, most fearful pressures, to retain their decency and to eventually prevail. It was possible and necessary to stand up against fascism. This plea fell upon increasingly difficult times—for Seghers, for Europe, and for the world. Publication—in English translation in the United States—had to wait until 1942, but then resulted in a bestseller and a Hollywood film with Spencer Tracy in the lead role.

Besides her anti-fascist novels, which began an ambitious project of recording the social, mostly working-class, history of Germany in the twentieth century, and was to be continued in later years, Seghers nurtured what was at the root of her creativity—her love and skill for storytelling. Throughout her life, and especially at difficult junctures in it, she produced a variety of stories and “mythic tales,” which constitute an important and perhaps the most intriguing part of her work. In the 1930s, as the trials and purges in Moscow frightened and divided Communists, Seghers wrote some of her most beautiful and enigmatic tales: “Die schönsten Sagen vom Räuber Woynok” (1938, The Most Beautiful Legends about the Robber Woynok), “Sagen von Artemis” (1938, Legends about Artemis), and “Die drei Bäume” (written 1940, The Three Trees). Her most “direct” comment on the events in Moscow was her radio play of 1937 about a famous mistrial in history, Der Prozeß der Jeanne d’Arc zu Rouen 1431 (The Trial of Jeanne d’Arc in Rouen). It carefully followed existing records and thus depended on the listener/reader for interpretation, an approach that served it well at the time and again in 1952, at the height of another show-trial—that of Rudolf Slánský (1901–1952) and his mostly Jewish co-defendants in Prague—when it was performed on stage by Brecht’s Berlin Ensemble. Neither in the 1930s nor early 1950s did Seghers speak openly against the Soviet purges, nor did she voice her disappointment when Hitler and Stalin concluded their “pact” in 1939. Although she later defended Stalin’s wily move—in her story “Die Kastanien” (1950, The Chestnuts)—at the time she was deeply disappointed and disoriented. The outbreak of World War II, Hitler’s rapid advances, his occupation of the northern part of France, and the installation of the Vichy government in the south threatened her and her family’s existence and forced her to flee once more, first to the south of France, which was quickly becoming a trap. She had two young children, was destitute, and her husband was in a French concentration camp. Then, with the help of comrades, friends, and the League of American Writers she managed to leave Europe via Marseille.

Exile in Mexico

After a long and perilous journey via Martinique, the Dominican Republic, and various small Caribbean harbors, Seghers and her family landed in New York on June 16, 1941, only to be denied even temporary entry, although that had been the family’s hope. They had to move on and went south to Mexico, which took in fugitives from the defeated Spanish Republic and included European Communists who had been supportive of the Republican cause, as had Seghers. A large and active exile community sprang up in Mexico City in which Communists played a leading if also controversial and divisive role. Seghers quickly assumed an important place in the exile communities’ cultural activities and took on the co-presidency of the Heinrich Heine Club, named after the famous German-Jewish poet and exile whom she had loved and admired since her youth.

It was during her Mexican exile, especially towards the end of the war and in its immediate aftermath, when knowledge about the extent of the Holocaust and discussion about Germany’s post-war fate became wide-spread, that Seghers began to pay more attention to her own Jewish heritage, particularly in her only ostensibly autobiographical story “Der Ausflug der toten Mädchen” (written in 1943/1944, published in 1946, The Excursion of the Dead Girls) and in “Post ins gelobte Land” (written in 1945, published in 1946, Mail to the Promised Land). When Seghers wrote these stories, which are among her best, she knew of the fate of her parents: Her father had died in 1940, after having been driven from his home and two days after he and his brother had been forced to “sell” the family business and property. Her mother, for whom a last-minute visa to Mexico had come too late, was deported on March 20, 1942, to the Piaski ghetto near Lublin in Poland without further record of life or death. Still, these stories—and Seghers’s essays from the time—do not advocate blanket condemnation of the Germans and Germany but plead for a new beginning which would create an egalitarian, socially just society where racism would finally be eradicated.

During her flight from Europe, Seghers began work on a novel that may be her best and most enduring: Transit (first published in English—Transit—and Spanish—Visado de tránsito—in 1944). Using mythic and literary allusions as well as closely observed details from her own and her friends’ experiences, the author presents the desperate plight of people who cannot stay where they are and have no place to go.

At the time of her flight Seghers had had little interest in Mexico. And in her six years there her gaze remained fixed on Europe and her expected return, no matter that apart from a serious accident they were good years, and she and her husband became citizens in 1946. Yet with time, and especially in retrospect, she came to love the country, its people, and its culture, particularly the painters and great muralists of the period. Some of them, including the most famous, Diego Rivera, she came to know personally.

While still in Mexico Seghers also set herself the goal of becoming a mediator between cultures and introducing Germans who had been shut off from the non-fascist world to the art and thought of others. After her return she focused on Latin America and wrote about Mexico in essays and fiction, e.g. in Crisanta. Mexikanische Novelle (1955, Crisanta, Mexican Novella). While Seghers always believed that the fight against oppression would have to go on irrespective of its toll on individual lives, and originally thought that the Soviet Revolution was indeed the “completion” of the French, her disappointment in post-World War II developments, including the ravages of Stalinism, made her increasingly concerned about the price of revolution as well as its betrayal and corruption. She was particularly intrigued by Toussaint-L’Ouverture (c. 1744–1803), the black slave who freed Haiti and ran it wisely until he was captured by Napoleon and deported to Europe where he died in prison. He is the subject of an essay and figures prominently in one of the two Caribbean Tales she wrote soon after her return to Europe, “Die Hochzeit von Haiti” (1948, A Wedding in Haiti), the other being “Wiedereinführung der Sklaverei in Guadeloupe” (1948, The Reinstatement of Slavery in Guadeloupe). The major character in “Die Hochzeit” is a Jewish merchant whose portrayal has earned Seghers the criticism of perpetuating negative Jewish stereotypes—in line with the widespread antisemitism and concomitant denial of Jewish roots among Communists in the Soviet bloc. Yet the story presents him as a faithful helper and scribe for Toussaint and a hero in his own unassuming way. In 1960 Seghers added a third story to her Caribbean Tales, “Das Licht auf dem Galgen. Eine karibische Geschichte aus der Zeit der Französischen Revolution” (The Light on the Gallows: A Caribbean Tale from the Time of the French Revolution). She again chose a Jew, a historical figure, as one of the main characters. This time the criticism was that Seghers did not give her hero any Jewish characteristics whatsoever. In general, critics have charged that Seghers, like other Communists, “denied her Jewish identity.” In fact she did not stress her Jewish origins but neither did she hide or reject them. She had left her faith and given her children a secular education, but ethically and imaginatively was deeply rooted in Jewish traditions and lore. Through her stories she indirectly stressed her Jewish comrades’ contributions to “the cause.” Even if she talked little about it in public, the Holocaust and her mother’s fate in it shaped her post-war vision. It made her cling even more desperately to socialism in which she saw the one chance to create a Germany and a world which would not allow the past horrors to recur.

Later Life in East Germany

Seghers returned to Europe in 1947, reaching Berlin via the United States, Sweden and France—alone. Her children were already studying in Paris, and her husband had remained in Mexico as a professor at the National University. Their original plan, which quickly proved unworkable, had been to lead a “bi-continental” existence. After her return Seghers’s commitment to help build a different Germany remained strong, but her discontent with life in Berlin grew with the heating up of the Cold War and the growing division of the country and city. Despite having been awarded the prestigious Büchner-Prize in 1947, a recognition which represented all of Germany, she did not feel “at home.” Her disappointment and sense of isolation at the time found expression in another of her intriguing mythic tales, “Das Argonautenschiff. Sagen von Jason” (1949, The Ship of the Argonauts. Legends of Jason). In the first years after her return Seghers spent much of her time outside Germany, especially in France, and became very engaged in the international, Soviet-backed peace movement of the time. At its meetings she renewed or formed many friendships with writers and intellectuals from other countries. Even when the German Democratic Republic, which became her country but never the home she longed for, closed in around her she continued to travel a great deal—and paid the price.

Soon after the founding of the two German states in 1949 Seghers was subjected to massive pressure from the new government of the GDR and its leader, Walter Ulbricht, to move to East Berlin, give up her Mexican passport and become a citizen of their state. At a time when Communists who like herself had returned from Western exile were investigated and persecuted, she had little choice but to comply, unless she wanted to relinquish her past social and political commitments and “flee” to West Germany. Seghers was lured and rewarded: In 1952 she received the International Stalin Peace Prize in Moscow, her husband was given a professorship at Humboldt University in Berlin and finally joined her, and she was made president of the GDR Writers’ Union, an office which she held until 1978. Throughout her tenure—she would have liked to step down earlier—she was a voice of reason and moderation against the recurring attacks on artistic expression and individual writers, but could make little substantive difference. She supported younger talents, most notably Christa Wolf (b. 1929). However, at crucial junctures such as the Workers’ Uprising in 1953, the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961, the Prague Spring of 1968 and the expulsion of the Jewish poet Wolf Biermann in 1976, she supported her party by either publicly defending or not publicly opposing its actions. Behind the scenes she was more outspoken in literary and cultural matters, but out of a sense of loyalty and discipline did not protest openly when the party used her, the “great name”, as was frequently the case.

Despite their repression, the 1950s still seemed a period of hope in which Seghers worked hard to put her talent at the service of the Party’s demands for writing about the newly emerging society. It did not come easy because as a returned exile she was—and, despite efforts to belong, remained—essentially an outsider. When she did deal with post-war and GDR reality, she wrote more soberly and critically than the East would have liked and the West gave her credit for. There is however no question that her works affirmed the ideas of socialist “Aufbau” (construction) which were being promoted in the GDR. And they presented West Germany as returning to the old social structures which had aided and abetted Fascism. Yet Seghers stressed values such as mutual trust, solidarity, community and tolerance as essential to the creation of a new society and subtly indicated that they were also in short supply on her side. Her novels Die Entscheidung (1959, The Decision) and Das Vertrauen (1968, Trust) in particular represent a major and to her exhausting effort to show what she wanted to see. They cover the period between 1947 and 1953 and end with the Workers’ Uprising, in which she has the Russian tanks stop outside her fictive steel plant: Workers themselves protect the plant against disgruntled colleagues and agitators, and the Party and Soviet Army leadership trust that they will do so. It was Seghers’s dream that the GDR would develop a truly socialist working class and a Party which could and would have faith in the people and did not need the Soviets to protect it.

Seghers’ faith in the righteousness of her own side received a heavy blow when Khrushchev exposed Stalin’s crimes in 1956, but she saw no alternative to socialism in the West. Thereafter, serious illnesses—with the first big episode at the end of 1955—marred her life and became more frequent from 1968 onwards. In part they may have been a consequence of an accident in Mexico, in part they were reactions to disillusionment and the pressures which she and others put upon her to uphold a semblance of hope.

Besides travel, including such far away places as Brazil and Armenia, writing continued to be her solace. While the novel project turned more and more into a self-imposed duty and was halted after the second volume—at some point Seghers had thought to take events to 1956—she returned to story telling with renewed vigor and allowed herself to range far from contemporary GDR reality in time, locale and subject matter. When she, albeit rarely, wrote about an East German setting, as in the story “Das Duell” (The Duel), she dealt with the early years. Yet disappointment in the current situation was ever present as was the wish to go beyond it. Her most direct attempt to treat the subversion of justice in the Soviet bloc was Der gerechte Richter, on which she worked between 1956 and 1964, but which she never published during her lifetime. The story appeared only in 1990 after Walter Janka, a former fellow exile and her publisher, had accused her of silence during his show trial in 1957 and caused a belated debate on Seghers’s lack of opposition to the abuses of the system. In more indirect ways, however, many of her stories and cycles of stories conceived and written after 1957 reflect her ambivalence between a utopian vision she was not prepared to relinquish completely because without it the world would be unbearable, and the suffering she saw everywhere, no matter what the historical or mythical setting. She desperately wanted to communicate hope and believed in the power of art and especially of story telling to uplift human beings. Between 1965, when her collection of tales Die Kraft der Schwachen (The Power of the Weak) appeared, and 1980, when her last darkly melancholy stories Drei Frauen aus Haiti (Three Women from Haiti) were published, Seghers produced a body of work which contains much that is fascinating reading. Many of these stories—such as Das wirkliche Blau. Eine Geschichte aus Mexiko (Benito’s Blue, 1967), Die Überfahrt. Eine Liebesgeschichte (The Crossing. A Love Story, 1971), or the collection Sonderbare Begegnungen (Strange Encounters, 1973)—invite multiple interpretations. In their time they also provided new directions for GDR literature to follow, such as an interest in Romanticism and the fantastic.

During the last years of her life Seghers felt more and more imprisoned by her body’s and her country’s failures. Yet she soldiered on to her death, which came in 1983. An impressive state funeral showed once more that she had allowed herself to be used as an icon for the government’s pretended union of intellectual and political life. Her reputation today suffers from this role and the political choices that led to it. It should not be forgotten, however, that her times and her circumstances were extraordinarily difficult ones and that her work at its best deals with them in ways that have earned her an important place in German literature. Her combination of social commitment and mythic vision are as rare as her style, which is harsh yet poetic.

SELECTED WORKS BY ANNA SEGHERS

Werkausgabe. Edited by Bernhard Spies. Berlin: Aufbau Verlag, 2000.

Gesammelte Werke in Einzelausgaben, 14 vols. Berlin, Weimar: Aufbau Verlag, 1977–1980.

Erzählungen, with afterword by Sonja Hilzinger. Berlin: Aufbau Taschenbuch Verlag, 1994.

Hier im Volk der kalten Herzen. Briefwechsel 1947. Edited by Christel Berger. Berlin: 2000.

There are no translations of the collected works into any language. Much has been translated into Russian, where there exists a selected works edition. Yet some of Seghers’s novels and tales, especially The Seventh Cross, have been translated into many languages, the most recent English language edition being The Seventh Cross, translated by James A. Galston, with a foreword by Kurt Vonnegut and an afterword by Dorothy Rosenberg. New York: 1987. There are also English translations of Revolt of the Fishermen of Santa Barbara and A Price on His Head (most recently in: Two Novelettes. Berlin: 1962), Transit, translated by James A. Galston. Boston: 1944; and Transit Visa, translated by James A. Galston. London: 1945; as well as of various stories, most notably “The Excursion of the Dead Girls” and Benito’s Blue and Nine Other Stories. Berlin: 1973.

Brenner, Michael. “We are the Unhappy Few”: Return and Disillusionment Among German-Jewish Intellectuals.” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies (April 2014): 1-11.

Fehervary, Helen. “Anna Seghers’s response to the Holocaust.” American Imago Vol. 74, no. 3 (Fall 2017): 383-390.

Fehervary, Helen. Anna Seghers. The Mythic Dimension. Ann Arbor, Michigan: 2001.

Hilzinger, Sonja. Anna Seghers. Leipzig: 2000. Seghers, Anna. Eine Biographie. 1947–1983. Berlin: 2003, which includes a comprehensive bibliographical overview.

also: Anna Seghers mit Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten. Reinbek: 4th ed. 2001.

Wagner, Frank, and Ruth Radvanyi, eds., with an essay by Christa Wolf. Eine Biographie in Bildern. Berlin, Weimar: 1994.

Wallace, Ian. ed. Anna Seghers in Perspective. Amsterdam, Atlanta: 1998.

Zehl Romero, Christiane. Anna Seghers. Eine Biographie 1900–1947. Berlin: 2000.

![Fink, Ida - still image [media] Fink, Ida - still image [media]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/mediaobjects/Fink-Ida.jpg?itok=dcqYYaRT)