Lore Segal

A respected and honored writer in a variety of genres, Lore Segal is beginning to get the wider recognition that she deserves. Much of her work is informed by her experiences as a refugee from Nazi-occupied Austria, one of the first children sent to England as part of the Kindertransport. The title of her first book, Other People’s Houses, indicates her sense of never fully being at home. In fictional works such as Her First American, Shakespeare’s Kitchen, and Half the Kingdom, as well as many pieces of non-fiction, Segal showed both wit and wisdom in bringing readers into her unique worldview. Hers was a long and fruitful career, demonstrated perhaps most clearly in the collection The Journal I Did Not Keep, published as she turned ninety.

Biography

Lore Segal was born on March 9, 1928, in Vienna, the only child of solidly middle-class parents; her father, Ignatz Groszmann, was chief accountant at a bank, while her mother, Franzi (Stern), was a homemaker. Her life changed dramatically, however, shortly after Hitler’s annexation of Austria, when she was one of a group of 500 Jewish schoolchildren quickly sent to England. For the next thirteen years she lived in several countries and with many different families—earning a B.A. from Bedford College, London, along the way—before finally achieving her independence and settling in New York. In 1961, Lore Groszmann married David Segal, an editor; they had two children, Beatrice and Jacob, before David’s sudden death in 1970. In addition to her writing career, Segal held teaching appointments at Columbia University, Princeton University, Bennington College, Sarah Lawrence College, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Ohio State University, from which she retired in 1995. She was an active writer into her nineties.

Literary Career

Segal’s experiences as a refugee formed the basis of her first significant publication, the novelistic autobiography Other People’s Houses (1964). Here she detailed her movements from Austria to England and eventually to the United States. This storyline was picked up in her third book, the autobiographical novel Her First American (1985), in which the naïve Holocaust refugee Ilka Weissnix is acclimated to American life by an alcoholic Black intellectual (based on Segal’s own relationship with the scholar Horace Cayton, Jr.). Through Ilka, Segal presents a compelling picture of the innocent newcomer who gradually loses her innocence the more she learns about her adopted country. Making use of a narrator with this kind of oblique relationship to America allowed Segal to comment incisively on both the country’s successes and its failures. Ilka returns (under a slightly different name, and now as a teacher at a think tank in Connecticut) as a key figure in many of the stories that make up Segal’s collection Shakespeare’s Kitchen (2007); the book was very well-received and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Segal’s novel, Half the Kingdom (2013), featuring many of the same characters from the think tank, including Ilka, is a meditation on aging and memory loss.

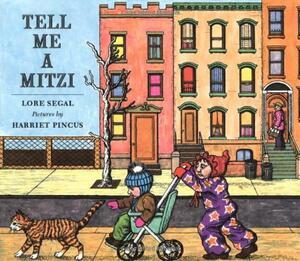

One of Segal’s primary interests was in storytelling itself, as seen in her translations and children’s books. Segal translated books of the Bible, which she saw as adventure stories, as well as fairy tales from the Brothers Grimm (in a volume featuring illustrations by Maurice Sendak). Her books for children were in a contemporary fairy-tale mode; her award-winning Tell Me a Mitzi (1970) features stories she had told her own children, all of which begin, “Once upon a time there was a Mitzi.” Segal’s second novel for adults, Lucinella (1976), also includes folk-tale and mythical elements in its satirical description of the members of a writer’s retreat (based on her time at the Yaddo institute). Indeed, a wry sort of humor is a hallmark of all of Segal’s writings.

Reception

Segal won numerous awards and fellowships during her long career, including having three stories included in O. Henry Prize volumes and being named a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2006, and her work has been increasing in popular and critical attention. Her First American, for example, which was well-reviewed upon its first appearance but failed to find much of an audience at the time, was republished in 2004 with a foreword by cultural critic Stanley Crouch. Seven of the stories that made up the Pulitzer-nominated Shakespeare’s Kitchen had originally appeared to wide readership and appreciation in The New Yorker. The publication of a career retrospective in 2019, The Journal I Did Not Keep: New and Selected Writing, prompted profiles in The Paris Review and Vanity Fair, among others. Segal’s work has been analyzed in a variety of academic periodicals, often in connection with her personal history in the Holocaust but in other contexts as well. Fellow writers such as Cynthia Ozick have also expressed their admiration for Segal’s work.

Lore Segal died on October 7, 2024.

Selected Works by Lore Segal

For Adults

The Journal I Did Not Keep: New and Selected Writing (2019).

Half the Kingdom (2013).

Shakespeare's Kitchen (2007).

Her First American (1985).

Lucinella (1976).

Other People’s Houses (1964).

For Children

More Mole Stories and Little Gopher, Too (2005).

Why Mole Shouted: And Other Stories (2004).

Morris the Artist (2003).

The Story of Mrs. Lovewright and Purrless Her Cat (1985).

The Story of Old Mrs. Brubeck and How She Looked for Trouble and Where She

Tell Me a Trudy (1977).

All the Way Home (1973).

Tell Me a Mitzi (1970).

Translations

The Story of King Saul and King David (1991).

The Book of Adam to Moses (1987).

The Juniper Tree and Other Tales from Grimm (1973).

Berger, Alan L. “Jewish Identity and Jewish Destiny, the Holocaust in Refugee Writing: Lore Segal and Karen Gershon.” Studies in American Jewish Literature 11 (1992): 82–95.

Boddy, Kasia. "Weissnex: Lore Segal and Her First American." In Narratives of Encounters in the North Atlantic Triangle, edited by Waldemar Zacharasiewicz and David Staines, pp. 309-323. Vienna: Verlag der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2015.

Cavenaugh, Philip. “The Present Is a Foreign Country: Lore Segal’s Fiction.” Contemporary Literature 34 (1993): 475–511.

Earnest, Cathy. “A Conversation.” Another Chicago Magazine 20 (1989): 153–167.

Franco, Dean J. “Recognition and Effacement in Lore Segal’s Her First American.” Race, Rights and Recognition: Jewish-American Literature Since 1969. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012.

Hadar, David. “The Ungrateful Child Refugee: The Anti-Sensationalism of Lore Segal’s Other People’s Houses.” A/B: Auto/Biography Studies 32 (2017): 667-672.

McCarthy, Kyle. “The Impossible Life of Lore Segal.” The Paris Review June 25, 2019. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/06/25/the-impossible-life-of-l…

Ong, Han. “Lore Segal.” Bomb 99 (2007): 80-86. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/lore-segal/

Tabor, Mary L. “A Conversation with Lore Segal.” The Missouri Review 30.4 (2007): 53-63.

Weir, Keziah. “Lore Segal Is Still Making Edits Even 50 Years Later.” Vanity Fair, June 21, 2019. https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2019/06/lore-segal-journal-i-did-not-k…;