Dame Miriam Rothschild

Inheriting her love for natural history from her father, Dame Miriam Rothschild was a renowned British scientist who published over 300 scientific papers throughout her lifetime. She was the first woman to serve on the Committee for Conservation of the National Trust and the first woman to become a trustee of the British Museum of Natural History. She served in presidential and committee member capacities for a large number of scientific societies pertaining to zoology, entomology, marine biology, and wildlife conservation. In 1985 she was made a Fellow of the Royal Society and credited for her groundbreaking work in the histology, morphology, and taxonomy of fleas. In 2000 she was made a Dame of the British Empire for services to Nature Conservation and Biochemical Research.

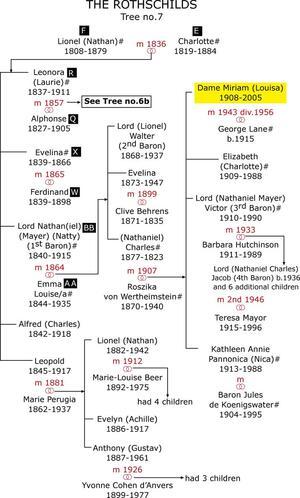

Born on August 5, 1908 in Ashton, Northamptonshire, Miriam Louisa Rothschild was the first child of the Honorable (Nathaniel) Charles Rothschild (1877–1923) and Roszika von Werthemstein (1870–1940). Dame Miriam was a world authority on fleas, a pioneer of the organic movement, and an ardent campaigner for the protection of animals and wildlife conservation.

Family History

At her home in Ashton Wold, a drawing of Dame Miriam’s ancestor, Nathan Mayer Rothschild—founder of the English branch of the banking dynasty—hung discreetly on one wall, while above the fireplace there was an oil painting of her glamorous mother, a champion lawn tennis player in Hungary whose family were the first Jewish family in Europe to be ennobled.

Dame Miriam’s father, Charles Rothschild, was the second son of Nathaniel Mayer, the first Lord Rothschild (1840–1915) and Emma Louisa von Rothschild (1844–1935). He worked in the family’s banking business and was a dedicated naturalist in his spare time, renowned for having identified the rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopsis) that carried bubonic plague. He met his future wife, the daughter of Captain Alfred von Wertheimstein, on a butterfly-collecting trip to Transylvania. Dame Miriam’s earliest memories were of a visit to her mother’s family in Hungary (in an area since annexed by Romania) when she first discovered her own entomological leanings. “One of my great joys was catching ladybirds and I asked my father how it was that one ladybird had more spots than another. I also remember that I could tell a comma butterfly from a small tortoiseshell butterfly, both of which look very much alike even now if I look at them.”

At the outbreak of World War I, the family returned to England and stayed with Dame Miriam’s grandfather, the first Lord Rothschild, at his home in Tring, before moving to Arundel House in Kensington Palace Gardens in London. Stretching from Bayswater Road to Kensington High Street, Kensington Palace Gardens is one of the most prestigious private roads in the world. Arundel House is now the Romanian embassy.

Early Life

Dame Miriam had two sisters and a brother: Elizabeth Charlotte (1909–1988), (Nathaniel Mayer) Victor (1910–1990) and Kathleen Annie Pannonica (1913–1988). Pannonica, better known as Nica, married Baron Jules de Koenigswarter and became a devoted patron of the New York jazz scene. Elizabeth, nicknamed “Liberty” by Dame Miriam, won an art scholarship to the Paris Conservatoire but was later diagnosed as a schizophrenic and lived with a household of caregivers. Eventually, she came to stay with Dame Miriam in Ashton Wold until her death at the age of 78, inspiring Dame Miriam to create the Schizophrenia Research Fund, dedicated to promoting the understanding, treatment, and cure of schizophrenia and other mental illnesses.

Charles Rothschild’s tragic death in 1923 was a terrible shock to fifteen-year old Miriam. “For two years after his death I completely gave up natural history. I thought it was a cruel and terrible thing to catch all these wonderful butterflies and stick a pin through them. Then, when my brother went to Harrow which was a public school, he came home one holiday and said to me: ‘I’ve got a holiday task of dissecting a frog. Will you help me?’ We killed this luckless frog by chloroforming it. We made the dissection and I was so thrilled with what I found—the blood system which you could see without any trouble because it was near the surface of the inside skin of the frog—I went straight back into zoology with a pair of scissors in my hand.”

Dame Miriam and her brother Victor were the only brother and sister to have both been made Fellows of the Royal Society, “but of course my brother got into the Royal Society long before I did. Chiefly, I think it was prejudice against women because, except for the fact that I hadn’t been to a public school like my brother—I was educated, or uneducated, at home—I think I was always a rather better zoologist than he was.”

As a child, Dame Miriam spent her summer months in Ashton Wold. “We never went to school, and so my sisters and I used to have to sit at a wooden desk, and were taught by an elderly governess. I was hideously bored by the lessons and the easiest way to get away from the old governess was by playing tennis tournaments in the summer and going hunting in the winter.” Dame Miriam was vehemently opposed to fox hunting. “It’s a cruel, unnecessary sport and very bad for children who learn violence and disagreeable habits from hunting. There’s only one reason you could put forward ‘in favor’ of hunting, which is that if there was no hunting, the fox would have been virtually exterminated because people would have been allowed to shoot them.”

Young Adulthood & Marriage

A member of the British branch of the international Rothschild family, marine biologist and zoologist Miriam Rothschild was a world expert on fleas, a pioneer of the organic movement and a passionate environmentalist. She is shown here with her three children (L to R), Charlotte, Charles and Johanna.

Courtesy of Miriam Rothschild

From 1928 to 1933 Dame Miriam took evening classes in zoology at Chelsea Polytechnic and developed an interest in marine biology. She then moved to Plymouth where she cultivated chicken food made from seaweed rather than grain. At the beginning of World War II Dame Miriam was drafted into the Enigma decryption project at Bletchley Park where she spent two years decoding German wireless messages.

Ashton Wold was turned into a hospital for wounded soldiers. One of those wounded soldiers was a handsome water polo champion, Captain George Lanyi (b.1915), a non-practicing Hungarian Jew whose name had been changed to Lane for security reasons. Captain Lane had injured his arm in a parachute jump and met Miriam while he was recovering at Ashton Wold.

They married in August 1943. Four of their children reached adulthood; three died in infancy. Dame Miriam’s marriage to George was dissolved in 1957, but the certificates George won for his champion dairy cows at Ashton Wold still hang in the guest lavatory, while Dame Miriam remained good friends with George and his second wife, Elizabeth (b.1938), whom he married in 1963.

Professional Associations, Honorary Degrees, & Awards

Dame Miriam, who did not eat meat or wear leather, was a passionate advocate for animal rights. She fought hard to introduce anesthesia before castration of cattle and tried to set up a system of travelling slaughterhouses. Her father started the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves and Dame Miriam served on their chief committee for 30 years. Her list of other professional associations was extensive. She was the first woman to serve on the Committee for Conservation of the National Trust and she was also the first woman to become a trustee of the British Museum of Natural History (1967–1975). She became the President of the Society for the Study of Insects, vice-president of Fauna and Flora International, and served on committees for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Zoological and Entomological Research Council, the Marine Biological Association, the Royal Entomological Society, the Systematics Association, the Society for Promotion of Nature Reserves, the Zoological Society of London and the Linnean Society of London. From 1938 to 1941 she was editor of Novitates Zoological, the official publication of Tring Museum, and she also served on the publications committees of the Zoological Society of London and the Marine Biological Association.

Despite lack of formal academic credentials, Dame Miriam was awarded many honors for her scientific research and served as visiting professor of Biology at the Royal Free Hospital in London. She was an Honorary Fellow of St. Hugh’s College, Oxford. Her honorary degrees included a D.Sc. from Oxford University (1968), Gottenburg (1983), Hull (1984), Northwestern (Chicago) (1986), Leicester (1987), Open University (1989), Essex (1998), and Cambridge (1999). She was also an honorary fellow of the Biology Society, the Royal Entomological Society, and the American Society of Parasitology. In 1985 she was made a Fellow of the Royal Society. In her citation from the Royal Society, Dame Miriam was credited for her work in the histology, morphology, and taxonomy of fleas, for having made many distinguished advances in scientific knowledge, and for having been the first to establish that the reproductive cycle of rabbit fleas is under the direct control of the hormones of their host.

She became a CBE (Commander of the British Empire) in 1982, and in 2000 she was made a DBE (Dame of the British Empire) for services to Nature Conservation and Biochemical Research. She also received a Defence Medal from the British Government for her work at Bletchley Park, a Floral Medal from the Lynn Society (1968), the Wigglesworth Gold Medal from the Royal Entomological Society (1982), a Silver Medal from the International Society of Chemical Ecology (1989), a Mendel Award from the Czech Science Academy (1993) and a number of gold medals from the Royal Horticultural Society for fruit and vegetable cultivation and for wildflower cultivation.

Publications & Scientific Legacy

From 1918 until her death in 2005, Dame Miriam published over 300 scientific papers. She revealed that wood pigeons with darkened plumage were suffering from tuberculosis of the adrenal glands and were a major source of avian tuberculosis among cattle. In another paper she observed that warning coloration in insects is directed against predators that hunt by sight and that insects also produce odors to protect themselves against predators that hunt by smell. In 1972 she provided the first description of the flea’s jumping mechanism.

Her first book, co-written with Theresa Clay, Fleas, Flukes, and Cuckoos; a study of bird parasites was published in 1952. Over the next 30 years Dame Miriam collaborated on a six-volume series cataloging her father’s collection of fleas—the largest such collection in existence: An illustrated catalogue of the Rothschild Collection of Fleas (Siphonaptera) in the British Museum (co-authored with G.H.E. Hopkins, Robert Traub and John F. Hadlow; Vol. I 1953, Vol. II 1956, Vol. III 1962, Vol. IV 1966, Vol. V 1971, Vol. VI 1983). Other works include a biography of her uncle Walter, Dear Lord Rothschild: birds, butterflies and history (1983), The Butterfly Gardener (with Clive Farrell, 1983), Colour Atlas of Insect Tissue: via the flea (with Yosef Schlein and Susumo Ito, 1985), Animals and Man (1986) based on her Romanes Lecture in Oxford in 1985, Butterfly Cooing Like A Dove (1991), The Rothschilds Gardens (1996).

Dame Miriam’s last book, Insect and Bird Interactions, co-edited with Professor Helmut Van Emden for the Entomological Club (2004), explores the relationships between birds, insects and modern farming methods. Her contribution was a paper about the effects of a chemical called pyrazine and how its odor stimulates the memory of day-old chicks. A paper that Dame Miriam wrote subsequently revealed that if one subjects chickens to pyrazine, they lay larger eggs.

Her father’s legacy has been profound. In 1997 she and Peter Marren co-authored Rothschild's Reserves, Time and Fragile Nature, revisiting 182 nature reserves created by Charles Rothschild 85 years earlier to see what had become of them. Regrettably more than half had been damaged or destroyed. “All my life I’ve had close connections with organisations in this country trying to conserve nature,” said Dame Miriam. “Conservation, farming and landscaping should be closely linked if we’re going to succeed. When I was chairman of the local RSNC [Royal Society for Nature Conservation], I said that I’d only be chairman until we doubled our number of members, but that when we’d doubled it, I was going to leave. Everyone thought I’d be there for a long time, but within a year our numbers had doubled. For the first time in my life, I’ve seen a rise in consciousness in the population, although it’s far too little, but it’s going in the right direction.”

Dame Miriam died at home at Ashton Wold on Thursday, January 20, 2005.

Selected Works

Animals and Man. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986.

Butterfly Cooing Like a Dove. London: Doubleday, 1991.

Colour Atlas of Insect Tissues via the Flea. Co-authored with Yosef Schlein and Susumo Ito. London: Wolfe, 1986.

Dear Lord Rothschild: Birds, Butterflies and History. London: Hutchinson, 1983.

Fleas, Flukes and Cuckoos: A Study of Bird Parasites. The New Naturalist Series. Co-authored with Theresa Clay. London: Collins, 1953.

“Gigantism and variation in Peringia ulvae Pennant 1777, caused by infection with larval trematodes.” Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 20. 537-546. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e261/9b33bc84aecf074061615d6115a527d28…

The Butterfly Gardener. Co-authored with Clive Farrell. London: Michael Joseph/Rainbird, 1983.

The Rothschild Gardens: A Family Tribute to Nature. Co-authored with Kate Garton, Lionel De Rothschild, and Andrew Lawson. London: Abrams, 1997.

Gryn, Naomi. “Dame Miriam Rothschild: Naomi Gryn meets with a most remarkable Dame.” Jewish Quarterly 51, no. 1 (2013). 53-58. http://www.naomigryn.com/index_files/Miriam%20Rothschild.pdf

Gryn, Naomi and Anthony Tucker. “Obituary: Dame Miriam Rothschild. Zoologist, naturalist, academic and eccentric who was the Queen Bee of research into parasites and their hosts.” The Guardian, January 22, 2005. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2005/jan/22/guardianobituaries.obituaries

Van Emden, Helmut F. and John Gurdon. “Dame Miriam Louisa Rothschild. 5 August 1908 – 20 January 2005.” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 52, no. 1 (2006). 315-330.