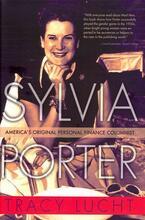

Sylvia Field Porter

Sylvia Field Porter, known for her clear writing and wise advice, was the first woman to write the financial section of a major newspaper. After her family’s ruin in the 1929 stock market crash, Porter studied economics and apprenticed at various investment counseling firms. Under the gender-neutral byline S.F. Porter, she wrote financial advice columns for various journals, breaking into the New York Evening Post in 1935 and beginning a regular column there in 1938. The Post later realized that her gender was an asset and published her full name and picture alongside her popular column that explained economic concepts in layman’s terms. For the next two decades, she would pen countless columns and co-write a number of books.

As the first woman on the financial desk of a big-city newspaper and the first woman to break into the world of writing about finance, Sylvia Field Porter, economist, columnist, and best-selling author, was a pioneer for over half a century in educating the American consumer about money matters.

Career Beginnings

Sylvia (Feldman) Porter, the only daughter and second child of Russian Jewish immigrants, was born Sylvia Feldman on June 18, 1913, in Patchogue, New York, to Louis Feldman, a physician, and Rose (Maisel) Feldman. The middle-class, cultured family moved to Brooklyn, New York, where Sylvia’s father continued to practice medicine until he died of a sudden heart attack in 1925. After trying other jobs to support the children, her energetic and resourceful mother, who decided to change the family name to Field, became a successful milliner. She also insisted that Sylvia prepare herself for a career. Sylvia attended P.S. 99, skipping the sixth grade, and graduated from James Madison High School at age sixteen. Since Cornell University would not award her a scholarship because of her young age, Sylvia enrolled at tuition-free Hunter College in Manhattan as an English and history major, while continuing to live at home.

The stock market crash in the fall of 1929 severely affected the Field family when Sylvia’s mother lost an investment of $30,000. Shocked by the family’s loss of financial security and determined to understand what had occurred, Sylvia switched her major to economics. She earned a Phi Beta Kappa key as a junior and the bachelor’s degree magna cum laude in 1932. Her involvement in the world of finance heightened in 1931 when she married bank employee Reed R. Porter. Unable to obtain work because of the Depression and because she was a woman, Porter apprenticed at a new investment counseling firm. Through this position and others on Wall Street, Porter acquired broad financial experience, augmenting her knowledge with business courses at New York University. Then, using the byline “S.F. Porter” to disguise her gender—her superiors did not want it known that she was a woman—she began to write articles for financial journals and a column for the American Banker. This enabled her to combine her love of writing with her growing expertise in investments.

Breaking into the Business

For several years, when Porter applied for jobs in person, she could not break the barriers surrounding the male-dominated business and financial world. Eventually, she obtained a free-lance position with the New York Evening Post in 1935, simply because the managing editor considered hiring a woman amusing. Readers, however, increasingly turned to Porter’s articles, since they explained economic issues and injustices in lay terms. In 1938, the Post made her its financial editor, and she began to write a daily column, “Financial Post Marks,” later changed to “S.F. Porter Says.”

When the Post realized that Porter’s gender was an asset, it changed her byline on July 15, 1942, to “Sylvia F. Porter” and added her photograph to the column. In an interview for New Women in Social Sciences, Porter reflected, “On that day I became a woman.” The revelation that S.F. Porter was a woman resulted in more requests for lectures and for columns in other magazines. While she did not neglect the experts—she founded Reporting on Governments, a weekly newsletter for the banking and securities community, in 1944—Porter had the greatest impact on her popular audience. In 1947, her column became nationally syndicated, and she began to publish comprehensive yet commonsense guidebooks on personal finance. With tax expert Jacob Kay Lasser, Sylvia Porter wrote How to Live Within Your Income (1948), Money and You (1949), and Managing Your Money (1953, 1962). From 1960 until her death in 1991, Sylvia Porter’s Income Tax Guide appeared annually.

She educated the public about investments and money management, partially by eliminating “bafflegab,” her term for the cryptic terminology of government and finance, and she devoted much of her work to consumer advocacy. In an interview in Particular Passions: Talks with Women Who Have Shaped Our Times, Porter said, “I like to think I’ve contributed in some way to the increasing willingness of the American public to take on the responsibilities of the economy.” She steered clear of involvement in politics, but consented to participate in President Gerald Ford’s economic summit in 1974 and to serve as chair of his nonpartisan Citizens Action Committee.

Legacy and Accolades

Over the next two decades, Porter issued several books to assist the American consumer in navigating the maze of available financial choices. Sylvia Porter’s Money Book: How to Earn It, Spend It, Save It, Invest It, Borrow It, and Use It to Better Your Life was a 1,105-page handbook based partially on a quarter century of her columns. It promptly made the best-seller list of the New York Times in 1975 and sold more than a million copies. Sylvia Porter’s New Money Book for the Eighties: How to Beat the High Cost of Living—And Use Your Earnings, Credit, Savings, and Investments to Better Your Life was also a best-seller. Previously, economists and financial advisers had assumed that money was handled by men, so women didn’t need to know the ins and outs of money management (some even thought money was too complicated for women to grasp). Sylvia Porter was the first to say (actually, shout) that women had a responsibility to understand—and to enjoy—money. In 1978, after more than three decades with the Post, Porter’s five-times-a-week column moved to the New York Daily News. Through the Field Newspaper Syndicate, it appeared in 450 newspapers and reached 40 million readers around the world.

Her accolades included numerous honorary doctorates and awards. Sylvia Field Porter was a trailblazer as a female journalist and economist in the traditionally male-dominated field of finance. For more than five decades, financiers and laypersons alike utilized Porter’s counsel in making business and money decisions, earning her the designation of one of America’s most influential women.

Sylvia and Reed Porter divorced in 1941. She married G. Sumner Collins in 1943. Collins died in 1977. They had one daughter, Cris Sarah Del Cuore, a classical pianist and music teacher, now of Norway, Maine. Porter also had a stepson, Sumner C. Collins, of Medical Lake, Washington. On January 2, 1979, Sylvia Porter married James F. Fox, a public relations executive. She died of emphysema on June 5, 1991, in Pound Ridge, New York, survived by her husband, daughter, two grandchildren, stepson, and brother, Dr. John Feldman, a California physician.

Selected Works

How to Get More for Your Money (1961)

How to Live Within Your Income, with Jacob Kay Lasser (1948)

How to Make Money in Government Bonds (1939)

If War Comes to the American Home, How to Prepare for the Inevitable Adjustment (1941)

Love and Money (1985)

Managing Your Money, with Jacob Kay Lasser (1953. Revised 1962)

Money and You, with Jacob Kay Lasser (1949)

The Nazi Chemical Trust in the United States (1942)

Sylvia Porter’s A Home of Your Own (1989)

Sylvia Porter’s Financial Almanac for 1983 (1982)

Sylvia Porter’s Guide to Your Health Care: How You Can Have the Best Health Care for Less (1990)

Sylvia Porter’s ... Income Tax Book (1981–. Annual)

Sylvia Porter’s Income Tax Guide (1960–1991. Annual)

Sylvia Porter’s Money Book: How to Earn It, Spend It, Save It, Invest It, Borrow It, and Use It to Better Your Life (1975)

Sylvia Porter’s New Money Book for the Eighties: How to Beat the High Cost of Living—And Use Your Earnings, Credit, Savings, and Investments to Better Your Life (1979)

Sylvia Porter’s Personal Finance Magazine (1983–1989)

Sylvia Porter’s Planning Your Retirement (1991)

Sylvia Porter’s Tax Saving Tips (1988–1990. Annual)

Sylvia Porter’s Your Finances in the 1990s (1990)

Sylvia Porter’s Your Own Money: Earning It, Spending It, Saving It, Investing It, and Living on It in Your First Independent Years (1983)

Your Financial Security (1987)

American Jewish Biographies (1982).

The Annual Obituary 1991 (1991).

Bird, Caroline. Enterprising Women (1976).

Bowman, Kathleen. New Women in Social Sciences (1976).

Current Biography Yearbook (1980, 1991).

Fowler, Glen. “Sylvia F. Porter, Financial Columnist, Dies at 77.” NYTimes Biographical Service 22, no. 6 (June 1991): 571.

Gilbert, Lynne, and Gaylen Moore. Particular Passions: Talks with Women Who Have Shaped Our Times (1981).

Mooney, Louise, ed. Newsmakers: The People Behind Today’s Headlines (1991).

New York Daily News, July 24, 1979, 39.

Obituary. NYTimes, June 7, 1991, B6.

People Magazine (October 29, 1979): 35–39.

Time (November 28, 1960): 46–52.

Woman Alive! KERA-TV, WNET/13 (1972). Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College, Cambridge, Mass.