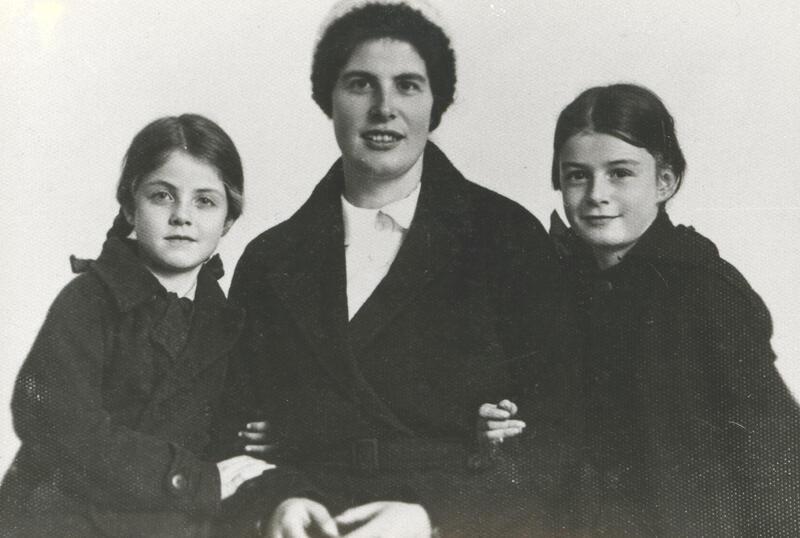

Clara Asscher Pinkhof

Clara Asscher Pinkhof left her hometown of Amsterdam for the northern province of Groningen in 1919 when she married Rabbi Abraham Asscher, whom she met through a network of children’s charity activists. In 1940 she returned to Amsterdam to fill a shortage of teachers in the Jewish schools, until she was arrested by the Nazis in May 1943 and deported to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. She was released to Palestine in July 1944 in an exchange for German nationals imprisoned there by the British, and she remained there for practically the rest of her life. After the war she released Sterrekinderen (Star Children), which depicted the lives of Jewish children during the German occupation and has since been translated into several languages.

Family

Not a great deal is known about this prominent Orthodox Jewish writer, who had a huge readership in her day. She was born in Amsterdam, the daughter of a doctor, and became a schoolteacher in the remote provincial village of Deil. In 1919 she married the Groningen Rabbi Abraham Asscher (d. 1926) and moved north from Amsterdam, where she had been briefly involved in charity work. Clara had met her husband through a network of children’s charity activists working in poor Jewish neighborhoods. As she later explained, they had been reaching out to the Lumpenproletariat community (poor and unpoliticized members of the working classes) and never came in contact with socialism.

Writing

In 1918, Pinkhof published her first book, a collection of Jewish children’s songs. Her aim was to acquaint Jewish children with the Jewish tradition, which she and her husband felt was under severe threat from assimilation.

As an Orthodox woman, Pinkof believed girls should be raised as good housewives and mothers. We find her name in the lists of those giving needlework classes to Jewish girls from deprived families. It was here that she started to tell stories, enlivening the girls’ long evenings with fantasies about traditional Jewish life, set down as Van twee Joodsche vragertjes (Two Small Jews Ask, Amsterdam 1919), and the past.

In 1926 Pinkof’s husband died, but she stayed in Groningen and earned a living as a writer. In the 1930s, she wrote stories for children and articles on charity work for newspapers and weeklies, as well as the children’s book Rozijntje van Huis (Rosi, The Little Raisin Leaves Home, Amsterdam 1934).

Imprisonment

In 1940 Pinkof returned to Amsterdam to work in the Jewish school, where there was a shortage of teachers for the newly established Jewish schools under the German occupation. She published regularly in Het Joodse Weekblad (The Jewish Weekly), a journal set up by the Jewish Council created during the German occupation, until the Nazi censorship became too much for her. She was arrested by the Nazis in May 1943 and sent to Bergen Belsen. She was transported to Palestine in July 1944 as part of an exchange for German nationals interned there by the British mandatory government.

After the war she continued her work on Sterrekinderen (Star Children), which she had begun before her deportation. She returned briefly to Amsterdam but soon went back to Israel.

The Post-War Period

Pinkhof’s motivation for writing was not simply a question of material need. She also wanted to share with a larger audience her feelings about what had happened to those she had worked with and loved. Sterrekinderen (Dutch 1946; German 1961; English 1987), her most moving book, which was translated into several languages, expressed her love for the children playing in the sun on the eve of the disaster. She portrays their poverty by describing their ragged clothes, the dirt on their bodies, their ignorance, and their joy at playing together in the street; they don’t yet know what is going to happen to them. She described crowds of star children “who did not live long and happily, whose stars were torn off by God himself and placed among the other stars in the heavens, as eternal evidence,” as she phrased it. In 1966 Danseres zonder Benen (Dancer without Legs) appeared, a book that describes her problems with raising her children, her psychological problems, and her attitude to religion.

Clara Asscher Pinkhof was a nostalgic and realistic writer, who had not read much literature written by other authors. When I interviewed her in the early 1980s, at her last home in Haifa, she told me that she did not need many books. She knew enough becauseh she had so many images in her head. She showed me a shelf of the many editions and translations of her own work. She was filled with stories, she said.

Clara Asscher Pinkhof never became a sophisticated writer, but she is still worth reading. She is at her best in Danseres zonder Benen.(Dancer without legs) As the title suggests, the theme here is loss, dealt with metaphorically. She died in 1984 in Haifa, at the age of eighty-eight.

Selected Works

Star Children. Translated by Terese Edelstein and Iner Smidt. Detroit, MI: 1987.