Lea Nikel

Lea Nikel was an important Israeli artist who began painting in the 1950s. Born in Ukraine, she immigrated to Palestine in 1920. During her stay in Paris in the 1950s, she exhibited in Israel and earned praise from critics. Her paintings were considered daring, as she utilized paint, collage, scratching, and areas of bare canvas. Her expressive abstraction, spontaneity, and strong coloring were different from the style of her teachers from the New Horizons group. She belonged to no art group or movement and over the years did not change her distinctive style. Although Nikel claimed she was born a feminist, she opposed the distinction between men and women artists and insisted that she should be judged as an “artist,” with no gender associations.

Lea Nikel, one of the central pillars of Israeli painting, had more than fifty years of magnificent creativity to her credit. She belonged to no art group or movement and over the years did not change her distinctive style, even when new styles became fashionable. Nikel believed that the painter’s homeland is her/his studio, the place where she/he creates. She did not attach any importance to locality or identity as an Israeli. Nikel traveled extensively all over the world and lived and created in Paris, New York, and Rome. In Israel she lived in Tel Aviv, Safed, and Ashdod and later, with her husband, Sam Leiman, in Cooperative smallholder's village in Erez Israel combining some of the features of both cooperative and private farming.Moshav Kidron. Although Nikel said that she was born a feminist, she opposed the distinction between men and women artists and insisted that she should be judged as an “artist,” with no gender associations. She also argued that an artist’s personal biography should be separated from her work, since it was not relevant to the value of her art.

Early Life and Family

Born in Zhitomir in the Ukraine, Lea Nikel immigrated to Palestine in 1920. She grew up mainly in Tel Aviv and at the age of sixteen began studying painting with Haim Gliksberg, one of the founders of the Painters and Sculptors Association in Tel Aviv, who encouraged her to go on painting. During the 1940s she married and gave birth to her daughter Ziva. These were difficult years in her life, due to financial problems and tension in her marriage, and therefore she did not paint at all. It was only after she separated from her husband that she enrolled (in 1946) in The Studio, established by Yehezkel Streichman and Avigdor Stematsky, and studied there for two years. Streichman and Stematsky were among the founders of the New Horizons group, together with Yosef Zaritsky, who was its leading figure. The members of the group were oriented towards a universal modern art and especially towards the “Lyrical Abstract,” expressing Israeli painterly values such as the local light and color. The Studio was founded in 1945 and was active until the outbreak of the War of Independence in 1948. Many of its students later became some of the best of Israel’s artists. Since most of the teachers and those who critiqued the students’ works were members of New Horizons, the group’s ideas greatly influenced the development of Israeli art.

Nikel knew the members of New Horizons well and studied with some of them at The Studio. She was also well acquainted with the painters who early in 1951 established The Group of Ten. Nonetheless, Nikel never associated herself with either of these groups, but developed a painting style of her own. In an interview she explained that in contrast to the members of New Horizons, who always painted nature, she absorbed impressions and experiences from nature but processed them into a painterly language of her own.

1950s Paris Period

Nikel left for Paris in 1950 and stayed there until 1961. Paris before and after World War II was an important art center, a place of pilgrimage for artists from all over the world, including Israel. Her original plan had been to go there for a short period, to study paintings at first hand, not from reproductions. In addition, in Israel she had felt stifled and enclosed. Nikel had to leave her daughter behind in Israel, and the decision to choose between art and motherhood was a difficult one for her. But her desire to go out into the world and to expose herself to international art proved stronger than her motherly feelings and she left her daughter with relatives in A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz Kefar Ruppin.

As she told it, she was very much influenced by the art scene in Paris, by the exhibitions she visited and by the cultural diversity that characterized postwar Paris. She enrolled in the Académie des Beaux Arts, but did not continue studying there. She later said that she learned more from the painters—from the daring of Picasso, who had no fear of the canvas and painted in whatever way occurred to him, from the intensive use of color by Matisse, and from the sensitive brushstrokes of Bonnard. She also said that although she had already decided to choose art as her profession while still studying at The Studio, it was only in Paris that she began relating to herself as a professional artist: “There I learnt discipline in work as an artist.” During her first years there she painted portraits, still lifes, and landscapes seen through a window. She was much influenced by the School of Paris, one of whose members was Pinchas Kremegne, whom she had met soon after her arrival in Paris. She painted in his studio and through him also became acquainted with other members of the group—especially the foreign artists, and primarily those of Russian-Jewish origin.

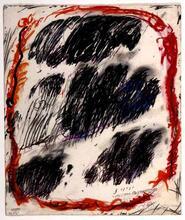

1954 was a turning point in her artistic development. Many styles that were flourishing in Paris at the time influenced her: Tachisme, Art Brut, the New Realism, Informal Art, and Concrete Art. She was especially influenced by the French painters Jean Fautrier (1898–1964), Georges Mathieu (b. 1921), and Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), as well as by American artists who were exhibiting in Paris at the time and whose works she was able to see, such as Mark Tobey (1890–1976), Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), Arshile Gorky (1904–1948), and Hans Hofmann (1880–1966). The American painters had begun exhibiting in Paris in the late 1940s and were in contact with their French colleagues. The connection was created through the French artist Mathieu, who was an Action Painter. In the wake of these influences Nikel began doing Non-Objective paintings, in the style of Abstract Expressionism and of Tachisme. (Tachisme, characterized by a spontaneity built on random stains and unpremeditated splashes of paint, is the European version of American “Action Painting.”)

Nonetheless, despite her tendency to Tachisme, Nikel attached importance to building a composition and creating a connection between its various components. In the introduction to the catalog Paintings 1963–1973 for her 1973 exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum (Helena Rubinstein Pavilion), the museum’s director, Dr. Haim Gamzu, wrote: “Many of her paintings start with a point, the point begins to move and creates a line, the line begins to curve and becomes an arc or a bend that the paintbrush fills with color, transforming it into a stain that at first glance appears to be placed on the canvas contrary to any congruity, in almost glaring contrast to its neighbor, and yet, wondrously, the confusion of colors does not turn into a clash, but concludes in harmonious perceptions in perfect balance.”

Already during her early years in Paris Nikel participated in group exhibitions, but her first solo exhibition was held in 1954 at the Chemerinsky Gallery in Tel Aviv, where she exhibited works from her early period in Paris and several new abstract paintings. Three years later, in 1957, she exhibited in the Netherlands and in the same year also in Paris, at the Colette Allendy Gallery. Nikel did not come to the opening because of a brain hemorrhage that affected her sight. It took her an entire year to recover from this event and to regain her sight. By 1959 she had recovered almost completely and her paintings from that period are characterized by their colorfulness, with scratchings and slashings on the paintings and on the monotype prints.

Artwork in 1960s and 70s

In 1961 Nikel returned to Israel and participated in an exhibition at the Bezalel National Museum and at the old Tel Aviv Museum in Dizengoff House, curated by Yona Fischer. In 1964, together with Arie Aroch and Ygael Tumarkin, she represented Israel at the Venice Biennale. But she soon left Israel again and in the years 1963–1964 lived in New York. In 1967, after the Six Day War, she moved to Rome, where she began painting on large canvases. She said that this happened due to congenial physical conditions, mainly because of the large studio that was placed at her disposal, but we cannot ignore the influence of the large canvases of the Abstract Expressionist painters of the New York School, who had influenced her in Paris in the 1950s and then again during her stay in New York in the 1960s. She said: “There’s a big difference in large-scale work. The body movements are entirely different. You raise your arm differently, you feel everything differently in your body.”

It is important to emphasize that although Nikel was aware of the changes occurring in the art field in the world and absorbed them, this influence did not always find expression in her paintings, and even when it did, it was not immediate but was sometimes apparent only later. For example, according to her, her monochrome and minimalistic paintings do not always belong to the period when other painters painted in a similar style. For this reason she was not always in fashion and was not always perceived as a relevant painter. In 1973 Nikel exhibited at the Tel Aviv Museum, in the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion. The exhibition earned her general appreciation as a painter of indisputable importance, yet at the same time the mainstream began to ignore her paintings, which did not fit in with the development of Conceptual Art that was dominant at the time in Israel. As a result, Nikel felt rejected and took some time out, not exhibiting in Israel again until the late 1970s. In 1973, after the The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur War, she returned to New York and stayed there for about four years, exhibiting all over the United States.

In New York Nikel began painting in water-based acrylic and using letters in script and in words—which points to the influence of Conceptual Art but also to an earlier influence, that of Pop Art. Concurrently, inspired by the Genji Tales—a Japanese saga written in the tenth century by a lady of the Emperor’s court—she painted a series of eight works on square formats with a tendency to the monochrome and a less congested picture plane. In other paintings, which are minimalist in style, Nikel connected herself with the philosophy and spirit of Zen Buddhism, through the rapid stain, the scribbled line and the vitality of her works, as well as through the incessant conflicts—for the continuous question-and-answer method is one of Zen Buddhism’s ways to attaining inner illumination.

Late Career and Legacy

Nikel continued to be a prolific artist, exhibiting frequently in galleries and museums. In 1995 a retrospective of her work was held at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and in the same year she was awarded the Israel Prize. In 2001 she exhibited works on paper at The Open Museum at the Industrial Park in Omer. At this exhibition she presented works done in different materials, such as oils on paper, watercolors, oil chalks, acrylic and collage. Encompassing fifty years of art creation, these works reflect the development of her artistic language into an abstract one. Through them we can also see the connection, in both ideas and styles, to the automatism of Joan Miró (1893–1983) and Paul Klee (1879–1940) and to the scribbles of Jean Dubuffet. In May 2002, she showed at the Sommer Contemporary Art Gallery, Tel Aviv, which generally exhibits young contemporary artists. In a further solo show mounted in July 2005 at the same venue, some of the works incorporated pieces of cloth taken from Nikel’s summer dresses.

Continuing to work to the very last, Nikel died of cancer on September 10, 2005.

Ahronson, Meir, ed. Lea Nikel Works on Paper. Ramat Gan: 1987.

Fischer, Yona. Lea Nikel: Book. Tel Aviv: 1992.

Gamzu, Haim. Lea Nikel: Oil Paintings 1963–1973. Tel Aviv: 1973.

Givon, Noemi, ed. Lea Nikel. Tel Aviv: 1990.

Heller, Sorin. Lea Nikel. Omer: 2001.

Forish, Orly. “Lea Nikel.” Seminar paper, including interview with the artist, Kidron Village, 1987, supervised by Prof. Gila Ballas (now in Beit Ziffer).

Sugata, Mutoko. “Lea Nikel.” Seminar paper, including interview with the artist, Kidron Village, 2001, supervised by Dr. Ruth Markus, Tel Aviv University, 2002 (now in Beit Ziffer).

Sgan-Cohen, Michael, ed. Lea Nikel. Tel Aviv: 1995.

Tadmor, Gavriel. Lea Nikel. Haifa: 1966.

Zalmona, Yigal. Lea Nikel. Jerusalem: 1985.

Idem. Lea Nikel: New Works. Tel Aviv: 2002.