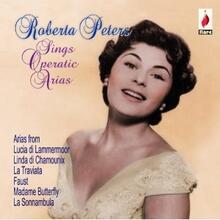

Erica Morini

Violinist Erica Morini (1904–1995) on board a ship.

Photograph of Erica Morini, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Erica Morini made her violin debut at age five, playing for Emperor Franz Joseph’s birthday party. First taught by her father, she went on to study in master classes at the Vienna Conservatory at age eight. She gave her first orchestral concert in Vienna in 1916 and debuted at Carnegie Hall in 1921 to great acclaim. Morini married in 1932 and settled in New York in 1938 but visited Vienna in 1949 to give concerts after the war. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s she toured the world, adding concerts to her overbooked schedule to accommodate her throngs of fans. Morini retired in 1976, the same year the city of New York honored her with a lifetime achievement award.

Early Life

According to official records, violinist Erica Morini was born in Vienna on January 5, 1904, although the year of her birth was sometimes cited as 1908—apparently in an effort to stress her precocity. Her father, Oiser (Oskar) Morini, was the proprietor of a music school in Vienna’s Second District. A student of both Jakob Grün and Joseph Joachim, he was a well-regarded and experienced musician and teacher. His wife Malka (née Weissman), who like him was a native of Chernovtsy (Czernowitz), was a trained pianist and worked as a piano teacher. Several of their children—the exact number of whom is not known—were also active in the arts. One daughter, Alice, was a pianist; another, Stella, a violinist; Haydee was a dancer. A son, Frank, was an art dealer who, during Erica’s later years, was always available to her backstage. Albert Morini, born in 1902, a pianist and later a manger, who went into exile in 1938, may have been another son.

Morini received her first musical training from her father. Her parents became aware of her musical talent even before she started taking violin lessons. As a little girl Erica listened to the lessons her father gave, and if a student played a wrong note, she immediately sang the correct note or pressed the appropriate key on the piano. During ballet lessons, people noticed her phenomenal ear and her extraordinary rhythmic soundness. She maintained her enthusiasm for dance her whole life.

Training and Early Career

At the age of five, Morini played for Emperor Franz Joseph at a surprise party for the emperor, at which she played behind a screen. Dumbstruck by the child’s unbelievable talent, the emperor offered to give her whatever she wanted. Little Morini wished for a doll with eyes that opened and shut, which, naturally, she received.

Morini apparently began her formal institutional instruction on the violin when she was accepted into the master class of Otakar Ševčik at the Vienna Conservatory at age eight, “as one of the first female students.” The youngest student who had ever passed the entrance examination, she passed the final examination when she was only eight. Morini supplemented her studies with private lessons from Jakob Grün and, after his death, from his student Rosa Hochmann, who had studied all three Bruch concertos with the composer. Morini liked to refer to this authority when asked about her interpretation. She took private lessons with Alma Rose and with Adolf Busch. Her studies with Ševčik informed her playing, especially his unique method of teaching left-hand technique, which was an important complement to the Grün and Joachim method for the right hand that her father had passed on to her. “When it comes to my training as a violinist, I am a mixture. … My right, bowing arm is Joachim, my left hand Ševčik.”

During the period of her training with Ševčik she took part in the competition for the state prize, emerging from the public performance as the clear winner. The prize money was nonetheless withheld from her, as she reported in an interview for Who Is Who in Music. “Before I was able to collect it, however, it was pointed out that the wording of the terms of the award specified its being given ‘to the man who …’ and for this reason the Prize Committee felt itself obliged to withhold the bestowal.”

In 1916 Morini gave her first orchestral concert in Vienna. Josef Krips, who was three years older than she, was in the audience: “She was a very young thing, I can still see her with the blue bow in her hair. She interpreted the A-Major Violin Concerto of Mozart wonderfully. … I remember in the second movement she was suddenly playing all alone. The orchestra had taken a break, so to speak. She refused to be deterred and just kept playing. After about ten seconds, the orchestra found its place again.” Arthur Nikisch heard the young girl and invited her to Berlin, where she appeared two years later under Wilhelm Furtwängler. She described her concert under Nikisch with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in 1919 as “the most important experience of my life. I was the only child who had been allowed to play there.” After this concert, Nikisch expressed his profound admiration: “This is not a Wunderkind, it is a wonder—and a child.” This catchy comment was quoted again and again in concert reviews.

On January 5, 1921, her sixteenth birthday, Morini embarked on her first trip to America accompanied by her father and her sister Alice. She had been engaged for sixty concerts in North and South America. Her American debut took place on January 26, 1921, in New York’s Carnegie Hall under Artur Bodanzky. According to the Neues Wiener Tagblatt, Morini received “unheard-of fees.” The image of the Wunderkind was obviously consciously cultivated, and clothing selected with this in mind. A photograph from this period shows a dark-haired girl with large dark eyes. A big white bow holds her hair back from her temples, and a lace collar emphasizes the childlike appearance.

Later Career

After her critically acclaimed concert debut in Carnegie Hall, Morini was presented with the Guadagnini violin of the American violinist Maud Powell, who had died the previous year. Powell had specified in her will that the violin was to go to the “next great female violinist.” Another honor she received, from the Society of Music in Madrid, was the embroidered handkerchief that Sarasate wore in his breast pocket when he appeared in concert and which he had left, in his will, to the best interpreter of his Spanish Dances.

In 1932, Morini married Felice Siracusano, a manager, art dealer and music lover from Messina, Italy. The marriage remained childless. She was of the opinion that family and an artistic career were incompatible.

After leaving Vienna for Budapest in September 1937, Erica Morini left Europe in 1938 together with her husband and settled in New York, where Morini, as a world-famous musician, belonged to the artistic elite and found herself in a privileged position; nor did she suffer any financial strains. The new place of residence that she had involuntarily chosen did not hamper her international career.

In 1949 Morini returned to her native city of Vienna for the first time in twelve years. She was deeply moved by the return to her birthplace: “I wept with excitement as I walked the streets of Vienna.” On October 3 and 8 Morini gave concerts in the Großer Saal of the Musikverein. She performed a solo concert with Otto Schulhof at the piano and an orchestral concert with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra under Rudolf Moralt. The critics were unanimous in their mention of her silken tone and musical vitality.

From the 1950s on only a few scattered mentions of her concert activities are to be found. In 1951, at the Casals Festival in Perpignan, she performed Mozart’s A-Major Concerto under Pablo Casals; in 1959, she appeared at the Salzburg Festival under George Szell. Strenuous tours to South America, Australia and the Far East followed. In 1968 she was invited to Israel to give twelve concerts. Her success was so overwhelming that she was forced to add two more.

In 1970 Josef Krips invited Morini to play in San Francisco. A letter from Morini to the conductor, dated January 20, 1970, confirms that the collaboration was harmonious. “Dear Kripschen, I believe this is my first real ‘fan’ letter, but I must tell you how much I enjoyed the concerts with you and how happy you have made me.” The list of conductors under whom Morini performed is impressive. Along with Krips they included Leonard Bernstein, Ference Fricsay, Wilhelm Furtwangler, Erich Kleiber, Otto Klemperer, Willem Mengelberg, Igor Stravinsky, George Szell and Bruno Walter. Her accompanists included Rudolf Firkusny, Leon Pommers and Ignaz Friedman. Many of Morini’s partners became mentors and friends. One of them was the violinist Bronislav Hubermann, who had played Bach’s D-Minor Violin Concerto for two violins with her in Budapest and Vienna. After a rehearsal he is said to have cried in admiration: “She played that so beautifully, that I have hard time [sic] to play it like she does.” Jascha Heifetz, another of her admirers, was especially fascinated by her staccato technique. He asked her to initiate him into the secret of this technique. His request embarrassed her, for although she had mastered staccato playing, she did not know how to convey it. From this experience she drew a lesson—it was necessary to pay individual attention to each of her students. It is no coincidence that Heifetz became her model.

Her repertoire was built around the well-known solo concertos of the romantic period, but also included less frequently played works—for example, all of the violin concertos of Ludwig Spohr, which she advised every violinist to learn. Works from the twentieth century, on the other hand, seldom appeared on her concert program.

Later Life

Morini gave her farewell concert in 1976, after withdrawing from concert life years before. It is thought that she never again touched her violin. She had repeatedly complained of disappointment that due to the narrow-mindedness and prejudice of many managers, women had a much more difficult time achieving success.

Along with the Guadagnini violin, Morini also played a Davidoff. The instrument, a Stradivarius from the year 1727, was named for a Russian cellist. Morini’s father had purchased it for her in Paris in 1924. Shortly before her death, as she lay in the hospital at the age of ninety-one, the instrument (as well as paintings, letters, and her scores, complete with fingerings and other valuable notes) were stolen from her apartment on New York’s Fifth Avenue. Morini was suffering from heart disease and in order not to excite her, the break-in was kept a secret. To this day, the theft has not been solved. Morini’s wish had been to divide the profit from the sale of the valuable instrument among three Jewish charitable organizations.

Four months after her death, Erica Morini was described in the journal The Strad as the “most bewitching woman violinist of this century.” Despite her phenomenal concert reviews and numerous prizes and awards—she received honorary doctorates from Smith College, Massachusetts, in 1955, and from the New England Conservatory of Music, Boston, in 1963, while the City of New York honored her lifetime achievement with a gold medal in 1976—and despite the respect in which she was held, Morini was soon forgotten.

CD booklet, Morini in Concert with Francescatto, Pommers and Waldmann. Arbiter CD 128.

Die Presse. October 8, 1949.

“Erika Morini spielt wieder in Wien.” Wiener Kurier, October 3, 1949.

Letter from Erica Morini to Margaret Campbell. In Campbell, Margaret. Die großen Geiger. Eine Geschichte des Violinspiels von Antonio Vivaldi bis Pinchas Zuckerman. Königstein: 1982.

Krips, Josef. Ohne Liebe kann man keine Musik machen. Erinnerungen. Vienna: 1994.

Martens, Frederick Herman. String Mastery: Talks with Master Violinists, Viola Players and Violoncellists; Comprising Interviews with Casals, Huberman, Macmillen, Erica Morini, Svečenski, the Members of the Flonzaley Quartet and Others. FA Stokes, 1923.

Neue Deutsche Biographie. vol. 18. Berlin: 1997.

Neues Wiener Tagblatt. January 6, 1921.

Roesler, Albrecht. Große Geiger unseres Jahrhunderts. Munich: 1987.

Who Is Who in Music. Chicago: 1940.

Wiener Kurier, October 3, 1949.

Zaimont-Lang, Judith. The Musical Woman: An International Perspective. Connecticut: 1984.

![blue.jpg - still image [media] blue.jpg - still image [media]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/mediaobjects/blue.jpg?itok=RkdKmpf6)