Fania Mindell

Feminist activist Fania Mindell immigrated to the United States in 1906. She ran a curio shop in Washington Square called Little Russia and eventually became a costume and set designer as well as translator for Broadway. At the same time, she became involved with Margaret Sanger and her sister, Ethel Byrne, and the trio co-founded the Brownsville Clinic in Brooklyn, offering information and contraceptives. Soon after, the clinic was raided, and all three women were arrested and charged with distributing obscene material. They were found guilty and fined, but the attention they garnered helped make contraception a national discussion and further the cause of women’s rights in America. In 1929, Mindell married historian Ralph Edmund LeClercq Roeder, a fellow theater-lover, and the couple became world travelers.

Early Life and Personal Details

Born in Minsk, Russia, on December 15, 1894, Fania Esiah Mindell emigrated to Brooklyn, New York, in 1906 with her family, and later moved to Chicago. She became a United States citizen in 1919. Mindell was a feminist activist, social worker, Broadway set and costume designer, consummate translator, and world-traveler. Alongside her contemporaries and her husband, historian and activist Ralph Edmund LeClercq Roeder, she spent most of her life pursuing leftist social activism and participating in and supporting the arts. Mindell’s true passion, however, was social activism and the advancement of feminist and progressive causes.

Activism and the Brownsville Birth Control Clinic

When leading birth control activist Margaret Sanger, together with her sister Ethel Byrne and Fania Mindell, opened the Brownsville Birth Control Clinic in 1916, birth control was illegal in the United States; indeed, it was not legalized nationwide in the United States until 1965, and then only for married couples. The landmark 1965 ruling was due in large part to the relentless efforts of the co-founders of the Brownsville Clinic fifty years earlier.

As an early leader in Chicago’s fight for birth control and other progressive causes, Fania Mindell, became acquainted with Margaret Sanger and Ethel Byrne in 1916. She helped make the arrangements for Sanger to lecture to stockyard women in Chicago, including rallying an audience of 1500 workers. Sanger described Mindell as among the idealists who “threw themselves into the fight for the oppressed as an aftermath of their own sufferings and repressions in Russia. She had a devoted and self-sacrificing nature which made her work, slave, toil for the love of doing it” (Sanger 197).

Sanger had recently returned to the United States after studying birth control clinics in Holland, and she was eager to share her knowledge and provide instruction about birth control practices to women in America. After their initial meeting in Chicago, Mindell, who was also enthusiastic about the cause, followed Sanger and took this fight to New York. Alongside Sanger, 22-year-old Mindell worked diligently in a campaign of civil disobedience in an effort to legalize and create access to birth control.

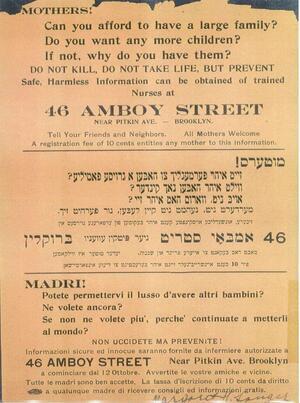

Sanger, Byrne, and Mindell aimed to open a birth control clinic in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, one of the borough’s poorest neighborhoods and one with a large immigrant population. To spread the word, they went door-to-door delivering handbills with information about the clinic. Mindell translated the handbill into Yiddish to better serve the large number of Jewish women in the neighborhood; other handbills were printed in English and Italian. The Brownsville clinic opened its doors to women of every race and creed on October 16, 1916; more than 100 women were served on opening day.

At the clinic, Mindell served several roles. Alongside Elizabeth Stuyvesant, she administered the clinic’s storefront, assisted with client intake and extensive record-keeping, and spearheaded communication efforts, facilitated by her fluency in three languages. Jewish mothers came to the clinic in droves, and Mindell’s primary role was interpreter for the Yiddish-speaking clientele. She was also responsible for reading information to women as they waited to be seen.

Ten days after the Brownsville clinic opened, New York vice squad members entered the building, locked and guarded the doors, and seized medical records for the clinic’s 464 patients. They also forced the women in the waiting room to line up and provide their names and addresses. The police arrested Sanger and Mindell on site; the two were taken to the local station house with a crowd of Brownsville mothers and patients trailing behind the police wagon in anger. They were arraigned and released on $500 bail after spending one night in jail.

Soon after, Ethel Byrne was arrested as well; she was tried on January 4, 1917, and found guilty of violating the statutory prohibition on providing information on birth control. Jewish women attended the trials, and many were subpoenaed in Byrne’s trial. The prosecution accused her of antisemitism, suggesting that she was trying to prevent the birth of Jewish babies, but many Jewish women protested and appeared on her behalf. She was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment in the Blackwell Island workhouse.

Sanger’s and Mindell’s trials began on January 29, 1917. Mindell was charged with selling Sanger’s birth control pamphlet, “What Every Girl Should Know” and was found guilty on obscenity charges and fined $50. Like her sister, Sanger was tried and sentenced for breaking the Comstock Laws, which “prohibited the distribution of birth control literature and other articles of ‘immoral use’” (Johnson 122). Sanger was sentenced to 30 days in a Queens workhouse.

In an April 1918 issue of The Birth Control Review, Sanger elaborated on the ordeal and offered thanks to women of New York who supported their efforts. She explained, “Day after day they came to the court and waited patiently for the case to begin. Other duties were put aside while they stood beside us in the fight for birth control, for woman’s right of ownership and dominion over her own body. All together, the year’s work can well be considered one of the greatest educational efforts of this generation” (Sanger 3-4).

In time, the women’s campaign led to major changes in social policy and to the laws governing birth control and sex education around the world. The Brooklyn clinic closed, but Margaret Sanger later became the founder of the American Birth Control League, the precursor to the Planned Parenthood Federation. In recent years, Sanger’s legacy has been called into question due to her connections with the eugenics movement.

Theater

In addition to working alongside Sanger and Byrne, Mindell was also a shop proprietor, costume and set designer, and skilled translator. She opened a small boutique called “Little Russia” in Greenwich Village, which featured Russian curios and was described as a place “where the pure Russian atmosphere prevails” (Arens 26). Robert Edmund Jones, a theater scenic, lighting, and costume designer, came to Little Russia in search of objects for the set of Arthur Hopkins’s production of “Redemption.” Once acquainted with Mindell, he invited her to assist with the set and costume design for the production. Jones was impressed with both her knowledge of the theater and her ability to construct and produce an authentic setting for the Russian play. Around the same time, Mindell submitted a translation of Maxim Gorky’s “Night Lodging” to Hopkins, which he produced at the Plymouth Theatre in 1920; Mindell also produced the models and stage settings for the show. She later adapted Leonid Andreyev’s “He Who Gets Slapped.”

Marriage and Expatriation

On December 3, 1929, Mindell married historian, activist, and author Ralph Edmund LeClercq Roeder. The couple shared passions for social activism, leftist causes, the arts, and theater. They spent many years traveling in Europe and the Caribbean but favored Mexico, where they moved in the 1950s, spending their later years as expatriates in Mexico City. Some scholars speculate that Mindell and Roeder moved to Mexico City in part because of their close associations with leftist causes during the McCarthy era, as well as Fania’s brother Jacob’s arrest and prosecution under the Smith Act, a 1940 law forbidding American citizens or residents from advocating, abetting, or teaching the violent overthrow of the United States government.

Legacy

Fania Mindell died on July 18, 1969, several months before her husband. They are both buried in the Panteón Civil de Dolores Cemetery in Mexico City. Remembered foremost as Margaret Sanger’s assistant and associate in the fight for birth control education, Mindell’s role is often downplayed or excluded from this story. In recent years, however, several journalistic endeavors have both brought the figure of Mindell to the fore and attempted to rewrite the role of Jewish women in the struggle for access to birth control. Not yet a citizen and only 22 years old, Mindell played a key role in the fight for birth control education in America. Moreover, through her commitment and contributions to the cause, Mindell invited scores of Jewish immigrant women into the fold.

Anhalt, Diana. A Gathering of Fugitives: American Political Expatriates in Mexico, 1948-1965. Santa Maria, CA: Archer Books, 2001.

Arens, Egmont. The Little Book of Greenwich Village: A Handbook of Information Concerning New York's Bohemia, with Which Is Incorporated a Map and Directory. New York: Egmont Arens at the Washington Square Bookshop, 1922.

Armstrong, Heather L. “Margaret Sanger.” In Encyclopedia of Sex and Sexuality: Understanding Biology, Psychology, and Culture, 594–96. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2021.

Balter, Lawrence. “Sanger, Margaret.” In Parenthood in America: An Encyclopedia. Volume 1, A-M I, I:527–31. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2000.

Chesler, Ellen. Woman of Valor Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Cox, Vicki. Margaret Sanger. New York, NY: Chelsea House, 2014.

“Fania Mindell Arrested for Distributing Birth Control Material.” Jewish Women's Archive, October 26, 1916. https://jwa.org/thisweek/oct/26/1916/fania-mindell-arrested-for-distrib…;

Feld, Lisa Batya. “The Translators and Spies of the Reproductive Rights Movement.” Jewish Women's Archive, March 15, 2017. https://jwa.org/blog/womens-history-month-translators-and-spies-of-repr…;

Johnson, Denise R. “Birth Control Laws and Advocacy in the United States.” In Women and Leadership: History, Theories, and Case Studies, edited by George R. Goethals and Crystal L. Hoyt, 84–90. Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire, 2017.

Klapper, Melissa R. Ballots, Babies, and Banners of Peace: American Jewish Women's Activism, 1890-1940. New York University Press, 2014.

Klapper, Melissa R. “The Drama of 1916: The American Jewish Community, Birth Control, and Two Yiddish Plays.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 12, no. 4 (2013): 502–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1537781413000340.

McDonough, Yona Zeldis. “The Unsung Jewish Woman Who Helped Found Planned Parenthood.” Lilith Magazine, August 29, 2017. https://lilith.org/2017/08/the-unsung-jewish-woman-who-helped-found-pla…;

Mindell, Fania. “Machine Millinery,” International Socialist Review 16, no. 3 (1915): 173-174.

“Opposition Claims about Margaret Sanger - Plannedparenthood.org.” Planned Parenthood, April 2021. https://www.plannedparenthood.org/uploads/filer_public/cc/2e/cc2e84f2-1…;

Planned Parenthood. The Birth Control Pill: A History. Planned Parenthood Federation of America, 2015.

Sanger, Margaret. Margaret Sanger: An Autobiography. 1st ed. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1938.

Sanger, Margaret. “Clinics, Courts, and Jails.” The Birth Control Review 2, no. 3 (April 1918): 3–4.

Stewart, Nikita. “Planned Parenthood in N.Y. Disavows Margaret Sanger over Eugenics.” The New York Times, July 21, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/21/nyregion/planned-parenthood-margaret…;

Stuyvesant, Elizabeth. “The Brownsville Birth Control Clinic.” The Birth Control Review 1, no. 1 (February 1917): 6–8.

“Who is Fania Mindell?” New York Times, January 11, 1920.

Wood, Robin. “A Radical in the United States: John Cowper Powys and the ‘Red Scare.’” The Powys Journal 29 (2019): 99-121.