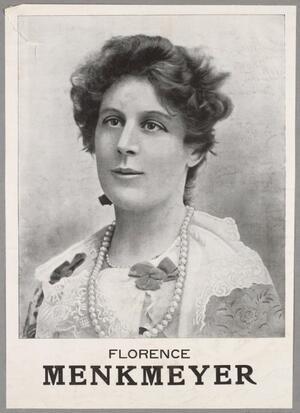

Florence Menk-Meyer

Australian pianist Florence Menk-Meyer, from Melbourne, took Europe by storm with her musicianship during her first visit there in the 1880s, before audiences in her home country were aware of her skills as a pianist, vocalist, and composer. She was a favorite of audiences overseas and in Australia for many decades afterwards, her achievements as a pianist compared to Liszt and other legendary masters. She was considered by some as the greatest female pianist of her generation worldwide, while as a vocalist she also drew extravagant praise. Yet she is hardly remembered today.

Florence Menk-Meyer was a world-renowned Australian pianist, composer, and dramatic soprano, acclaimed particularly as an interpreter of Beethoven, Chopin and Liszt. She was born around 1860 (the exact date is elusive) as Catherine Florence Meyer in the Melbourne suburb of St. Kilda to middle-class Prussian-born Jewish parents, Menk Meyer and Rebecca Fink, who had met and married in Australia. Menk Meyer, who had first emigrated to the United States, owned a prosperous general merchandise store in downtown Melbourne. He was related to the great Russian musicians Anton and Nikolai Rubinstein.

First European Tour

One of five gifted siblings, Florence showed uncommon talent as a pianist early in life, and in 1884 she set off for Europe with her older sister Milli (1856-1935), who was at that point an aspiring opera singer. Florence's intention was to perfect her keyboard technique under some of the leading continental maestros, including Anton Rubinstein in St. Petersburg, and afterwards, having showcased her talents in a series of public recitals in Australia, launch herself as a concert pianist. Her European trip exceeded all her expectations and kept her away from her homeland for five years. From the outset, she impressed her European teachers with her accomplishments as a pianist and potential as a composer. Using the stage surname Menk-Meyer in honor of her father, who had died in 1881, she was a sensation, first in Frankfurt and afterwards in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, St Petersburg and Moscow. She won extravagant praise from legends of the music world, critics, and audiences; she appeared at fashionable salons; she was fêted by high society and played for the Tsar and Tsarina. Misogynistic carping about female composers that niggled her in Vienna appears to have been the exception rather than the rule. Anton Rubinstein spoke for many when he declared that she played to perfection, and with her entire soul.

Menk-Meyer returned to Australia with Milli late in 1889, receiving a rapturous welcome and many requests to perform. Previously unknown outside her own circle, she had become a household name in Australia, owing to the very frequent reports of her overseas triumphs that were repeated in the Australian press. But fame and recognition for her kindled jealousy on the part of certain other Australian musicians, and at the end of 1890, having given a number of performances in Australia, she—and Milli—sailed for Europe again. There, further success awaited her starting in Rome.

Further Success Overseas

“It is both interesting and gratifying to note the enthusiastic reception which is accorded to [her] in places where the highest class of music is thoroughly understood, and, above all, where the musical portion of the press is not in the hands of jealous rivals,” pointedly observed Melbourne's Jewish newspaper in 1891. It quoted a glowing review of a concert she gave early in March that year at the Sala Dante in Rome, when “a numerous and brilliant assemblage” including “a large contingent of foreign notabilities” gathered to hear her. “She stands almost unrivalled as a pianiste, not only for her marvellous execution, but also for the sweetness and pathos of her play, the majesty of her touch in the forte passages, and, above all, the depth of her powers of interpretation.... Her own exquisite compositions called forth continued applause [and] gave us proof of the originality and strength of her creative faculties” (Jewish Herald, May 1891).

Further engagements in Italy and Switzerland ensued, and in the spring of 1892 Menk-Meyer dazzled in Paris. A little later she was in London, and soon afterwards she toured Holland and Scandinavia. Early in 1893 she triumphed with what was regarded as one of the best concerts of Berlin's winter season. In the spring of 1894, she gave a successful series of recitals in Brussels and then made her debut in Antwerp before a capacity audience. In May she concluded a tour of Holland, where—having been coached in Berlin by the renowned soprano Mathilde Mallinger—she sang Wagnerian opera as well as thrilling audiences with her own operatic works. Later in the 1890s she returned to Australia and New Zealand and enjoyed a successful career in the concert hall, on the radio, and in private recitals. In 1904 she turned down the offer of a teaching position at the Milan Conservatorium.

Slender, graceful, effervescent, and stylish, she was generally perceived as far younger than her actual years, even when she was over 40. Certain male music critics could not resist praising, in addition to her musical gifts, what they regarded as her rare physical beauty. She was described by a Parisian critic early in her career as another Liszt, a compliment widely repeated. Assessments of her playing often spoke of her “genius.” Her own compositions drew general high praise. As a lyric soprano she charmed critics and audiences alike with her sweet, clear, powerful voice.

Later Career

In 1912 Menk-Meyer and Milli, who had become a popular lecturer on the topography and socio-economic conditions of Egypt and the Holy Land, arrived in Jerusalem. There, Florence gave a concert in aid of impoverished Jews. The following year she arrived back in Australia with glowing newspaper reviews in French, Turkish, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic, memories of touring in Switzerland, and a successful season in Paris and of a meeting there with Zionist leader Max Nordau—an enthusiastic admirer of her musicianship—plus an invitation to be soloist at a new theater on the Champs Elysées.

The First World War checked Menk-Meyer’s European travels, and by the time it was over she was nearing 60. She continued to perform, in private recitals, on stage, and occasionally on the radio. Visits to Europe lessened, the Australian state of Queensland seemingly having become the sisters' most frequent destination outside Melbourne.

Milli died in 1935. In 1944 a feature article about Florence in a periodical devoted to music and musicians began: “To go a-swimming almost every day throughout the year at the age of eighty-four is even more rare than to achieve a world-wide reputation as pianist, vocalist and composer of [her] calibre” (Australian Musical News, July 1, 1944).

Predeceased by all but one of her siblings, Menk-Meyer died on May 31, 1946, and her brilliant career slipped into obscurity, probably largely due to the paper shortages during and immediately after the war, which precluded obituaries in the newspapers, and to the fact that so many people who remembered her at the height of her fame were dead too. Her name lives on only in a music prize at the University of Melbourne apparently endowed in 1975 by her sole married sibling's childless widow.

Argus (Melbourne), October 19, 1889; November 12, 1889.

Australian Musical News, July 1, 1944.

Australian Star, May 3, 1890.

Ballarat Star, February 27, 1890.

The Bulletin (Sydney), November 30, 1889; August 13, 1903.

Cootamundra Herald, October 7, 1908.

Daily Chronicle (London), January 31, 1888.

Daily Mail (Brisbane), October 22, 1924.

Dundee Evening Telegraph, January 31, 1888.

Hebrew Standard (Sydney), June 24, 1927.

Herald (Melbourne), October 10, 1931.

The Leader (Melbourne), September 30, 1905.

Lorgnette (Melbourne), October 26, 1889.

Illustrated Sydney News, May 10, 1890; June 7, 1890.

Jewish Chronicle (London), July 1, 1892.

Jewish Herald (Melbourne), February 8, 1888; October 25, 1889; November 21, 1889; January 19, 1890; May 23, 1890; May 20, 1892; August 12, 1892; September 21, 1892; October 5, 1892; February 8, 1895.

Queanbeyan Age, March 12, 1908.

Queensland Figaro, October 2, 1902.

Sydney Mail, March 18, 1908.

Sydney Morning Herald, August 20, 1903.

Table Talk (Melbourne), September 18, 1894; October 22, 1894.

Tasmania News, January 3, 1905.

Weekly Times (Melbourne), September 13, 1913.

West Gippsland Gazette, April 14, 1908.

Rubinstein, Hilary L. ‘“The Greatest Living Female Pianist’: Florence Menk-Meyer (1860–1946), A Forgotten Australian Virtuoso.” Australian Jewish Historical Society Journal, vol. 24, part 3 (2019): 437-67.