Bella Lewitzky

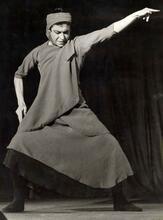

Dancer and choreographer Bella Lewitzky was as famous off stage as on, thanks to her battles for freedom of expression against the House Un-American Activities Committee and the National Endowment for the Arts. Lewitzky joined Lester Horton’s modern dance company in 1934, became his lead dancer, and helped develop his experimental technique. In 1940 she married fellow dancer Newell Taylor Reynolds, and the pair collaborated with Horton to create Dance Theater, a multi-racial troupe that performed politically progressive dances. She formed her own dance company in 1966, both choreographing and performing. She chaired the contemporary dance department at Idyllwild Arts Academy, was founding dean of the California Institute of the Arts’s School of Dance, and was a dedicated political activist throughout her life.

For more than six decades, Bella Lewitzky, a maverick in the world of modern dance, distinguished herself as a preeminent performer, choreographer, artistic director, educator, public speaker, and civic activist. With an unshakable preference for living on the American West coast, she defied norms that posited New York City as the center of American dance, maintaining the Lewitzky Dance Company in Los Angeles for over thirty years. She was also known for two highly publicized encounters with the federal government, risking professional ostracism to stand upon principle.

Early Life and Career

The second of two daughters, Bella Rebecca Lewitzky was born on January 13, 1916, to Joseph and Nina (Ossman) Lewitzky, Russian-Jewish immigrants living in a Southern California socialist utopian colony, Llano del Rio [Plain of the river]. The family relocated to San Bernardino, where Lewitzky attended high school. In 1934, when the family chicken ranch failed, she moved to Los Angeles to help her father find work. Lewitzky had always loved to dance but found ballet too restrictive. In Los Angeles, she was directed to Lester Horton, who introduced her to modern dance, and Lewitzky immediately felt at home. She collaborated with Horton for fifteen years, first as his pupil, but soon as his stellar protégé who could embody his wildly imaginative movement ideas.

On June 22, 1940, Lewitzky married Newell Taylor Reynolds, a Horton dancer who had recently graduated from the University of Chicago. During World War II, he served in the navy and eventually became an architect. He remained Lewitzky’s offstage partner, collaborating frequently as a set designer.

Dance Theater and Accusation of Communism

Returning to Los Angeles in 1946, Lewitzky and Reynolds, together with Horton and William Bowne, cofounded Dance Theater, a unique interracial institution, housing both a dance school and theater. They created dances critical of religious fanaticism, bigotry, the violent antisemitism of Nazi Germany, and the abuse of women. Notable examples are The Beloved (1948) and Warsaw Ghetto (1949). However, Lewitzky and Horton continued to disagree on the artistic mission and financial management of the company, including his decisions to create work for night clubs. Bowne resigned from Dance Theater in 1949. In 1950, when it became clear that Lewitzky had also begun to develop a diverging teaching methodology, the partnership with Horton ended.

In 1951, Lewitzky was anonymously accused of being a member of the Communist Party and was subpoenaed to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). An “uncooperative” witness, refusing on constitutional grounds to answer invasive questions, Lewitzky responded afterward to reporters with an often-quoted sound bite, “I am a dancer, not a singer.” From 1951 to 1965, Lewitzky taught modern dance in her school, Dance Associates, throughout Southern California, and at the University of Judaism. When her daughter, Nora, was born in 1955, she took a hiatus from performance.

Lewitzky Dance Company

At age fifty, Lewitzky formed the Lewitzky Dance Company, and in 1971 the company made its first cross-country tour into national prominence, with Lewitzky lauded by New York critics for an ageless and brilliant technique and a passionate performance style, particularly in her solo On the Brink of Time (1969).

The Lewitzky Dance Company achieved international status, touring thirty weeks each year, appearing in forty-three states and nineteen countries. It was one of three companies selected for the short-lived but highly successful IMPACT (Interdisciplinary Model Program in the Arts for Children and Teachers) artists in the schools program funded in the early years of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) (1970–1972). Lewitzky’s daughter, Nora Reynolds, first performed with the company in the premiere of Kinaesonata (1970) and was a member of the company from 1973 to 1978.

Lewitzky created more than fifty major concert works, several commissioned by national and international arts patrons. Spaces Between (1974) demonstrates Lewitzky’s expansive embrace of space with a translucent, swinging Plexiglas set designed by Reynolds. While producing dance for the Los Angeles Olympic Arts Festival, Lewitzky premiered her acclaimed universal statement of human survival in the gripping Nos Duraturi [We who shall survive] (1984)

Fight Against National Endowment for the Arts

On June 14, 1990, Lewitzky held a press conference at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, the scene of the 1951 HUAC hearings. In signing the contract for a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, she had refused on constitutional grounds to agree to the newly legislated policy requiring grantees to pledge not to create obscenity. With her were Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley and former blacklisted peers from the film industry. Referring to the McCarthy era, she asked, “How many times must history repeat itself? We must act. Having been witness, I must act.” Supported by the People for the American Way, Lewitzky filed suit, and on January 9, 1991, Los Angeles U.S. District Judge John G. Davies ruled in her favor, eliminating the pledge.

Lewitzky was chair of the University of Southern California’s contemporary dance department at Idyllwild (1956–1972) and founding dean of the School of Dance at the California Institute for the Arts (1969–1972). An outspoken advocate for government support of the arts, she served as vice-chair of the NEA’s dance advisory panel (1974–1977).

Awards and Legacy

Lewitzky received numerous awards, including six honorary doctorates, the Dance Magazine Award (1979), the first California Governor’s Award for Lifetime Achievement (1989), the American Society of Journalists and Authors Open Book Award (1990), the University of Judaism Burning Bush Award (1991), the National Dance Association Heritage Award (1991), and the Capezio/Ballet Makers Dance Foundation Award (1999). Lewitzky was also awarded the 1996 National Medal of Arts by then-President Clinton. The American Dance Festival premiere of Greening (1976) was the last group dance choreographed by Lewitzky in which she included herself. After that, she began a transition from the stage. With consistently strong performances, she quietly retired at age sixty-two.

Lewitzky remained dedicated to the art of dance, eloquently creating expressive human motion with exquisitely trained dancers. A champion of freedom of expression, she symbolized courage in her stand for constitutional rights in the public arena and courts.

On the occasion of Lewitzky’s eightieth birthday, she announced that 1996–1997 would be the Lewitzky Dance Company’s final season, concluding where the Company had first performed in 1966, at California State University, Los Angeles. At the company’s final performance in May 1997, Lewitzky cautioned her audience, “the arts are under threat more than ever before… What legacy I have left here will die unless you become responsible for keeping it alive.”

Lewitzky and Reynolds first retired to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to be near their daughter and two grandsons. In 1999, Lewitzky’s lower right leg was amputated due to long term arterial disease which had contributed to the end of her performing career in 1978. Returning to Southern California in 2001, she and her husband settled quietly into an assisted care facility in Pasadena. On July 16, 2004, at the age of eighty-eight, Bella Lewitzky died from complications due to a stroke. Lewitzky’s husband and daughter, Newell Taylor Reynolds and Nora Reynolds Daniel hosted a memorial celebration and remembrance of the life of Bella Lewitzky on December 18, 2004, at the Music Center in Los Angeles, where, in 1976, hers had been the first modern dance company to perform.

Lewitzky authorized three former company members to reconstruct dances from her repertory: Nora Reynolds Daniel, Walter Kennedy (Lewitzky rehearsal director 1990–1997), and John Pennington.

Bradburn, D. “Lewitzky makes rare appearance in NYC.” Dance Magazine 68, no. 10 (1994): 16-17.

Feliciano, R., and P. Ben-Itzak. "National arts medal to Bella." Dance Magazine 71, no. 3 (1997): 32-32.

Johnson, Lorin. “Degrees of Separation: Lester Horton’s: Le Sacre du printemps at The Hollywood Bowl.” Experiment 20, no. 1 (2014): 48-85.

Harrington, Heather. “The Reach of Bella Lewitzky.” Dance Education in Practice 6, no. 2 (2020): 13-18.

Moore, Elvi. “Bella Lewitzky: A legend turned real.” Dance Chronicle 2, no. 1 (1978): 1-78.

O'Neil, Robert M. “Artists, grants and rights: the NEA controversy revisited.” NYL Sch. J. Hum. Rts. 9 (1991): 85.