Lee Krasner

Despite putting her career on hold for years to aid her famous husband, Jackson Pollack, Lee Krasner achieved recognition in her own right as a gifted abstract painter. Krasner studied art at Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design. She worked a variety of jobs, creating murals and other public art. In the early 1940s, she met Pollack at her American Abstract Artists Group exhibit, and they married in 1945. She then became his business manager and they bought a farm to create a peaceful work environment. After Pollack’s death, she returned to painting, creating more emotionally expressive works. Her first retrospective was shown in 1965 at London’s Whitechapel Gallery. After her death the Museum of Modern Art did a retrospective, giving Krasner's work long-overdue respect.

This is so good, you would not know it was done by a woman. - Painter Hans Hofmann to his student Lee Krasner, in 1937

In 1951, Life magazine published a celebrated photograph of the “Irascibles,” eighteen artists who protested the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s refusal to exhibit modern art. This photograph defined the New York School of artists, a group committed to stretching the boundaries of modern art beyond cubism and surrealism. Despite the fact that Lee Krasner was a staunch supporter of the integrity of modern art, being one of two painters in New York working in completely abstract styles prior to World War II, the artist organizers of the photograph did not invite her to participate. After all, who was she but the wife of Jackson Pollock?

Early Life and Family

Fleeing antisemitism and the Russo-Japanese War, Lee Krasner’s father, Joseph Krassner, preceded his wife Anna and his five children in immigrating to the United States from Odessa in 1905. In 1908, he sent passage for his family to join him. Anna Krassner gave birth to her sixth child, Lee Krasner (born Lena Krassner but known as Lenore outside the family), on October 27, 1908, nine months after she arrived in New York and reunited with her husband. The first Krassner born on American soil, Lee Krasner would go on to forge other family firsts, female firsts, and artistic firsts.

The Krassner family lived in a traditionally observant Jewish home on Jerome Avenue in Brooklyn. They observed the laws of Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).Kashrut and spoke Yiddish among themselves. The children attended Hebrew school as a supplement to public education. As often proved the case in families of Eastern European descent, both father and mother contributed to the family income. They operated a produce store at the Blake Street Market in Brooklyn. Anna Krassner stood at the helm of the family business, directing the daily operation of the store. In her mother, Lee Krasner observed a strong female role model as a child. The elder Krassner sisters rejected their mother’s life-style, consenting to matrimony and lives as housewives in their teens. Krasner proceeded definitely in another direction—art.

Art Education

Krasner possessed the most extensive training and education of any of the New York School of artists. She began her odyssey of education in 1922. At age fourteen, she applied to Washington Irving High School in Manhattan, the only high school in New York City that permitted girls to study studio art. Admitted to the program, Krasner traveled daily the short subway ride to Manhattan that made a world of difference. In 1925, she graduated from Washington Irving, but not from Manhattan. Her education continued, via scholarship, at the Women’s Art School of Cooper Union. The training that Krasner received at Cooper Union, and later at the National Academy of Design, grounded her in technique from which she skillfully ascended into new artistic territory.

After graduation from Cooper Union, Krasner began her training at the prestigious National Academy. Students attended classes tuition-free, but promotion depended on the unanimous support of a professorial committee. Krasner’s individualist style rarely mustered support of a unanimous nature. Thus, when she applied for promotion to the academy’s life drawing class, several professors dismissed her self-portrait as a fake, believing that such an inexperienced artist could not produce a plein air self-portrait. Krasner explained her method. She used the woods behind her parents’ new home in Huntingdon, Long Island, as her setting. There, she nailed a mirror to a tree and painted what she saw. Krasner saw herself in nature.

Surrounded by trees, she stands tall in her 1930s self-portrait, with her red hair pushed behind her ears and paintbrushes held firmly in hand. She appears serious, determined. Art historian Barbara Rose comments on the self-portrait: “The defiant expression was characteristic of her tough minded attitude: She would submit to any discipline deemed necessary to achieve her goals of acquiring the techniques and skills necessary to produce great art, but she would do it in her own way and on her own terms.” The Academy of Design accepted these terms, promoting her to the life class, and onward, until she completed her studies in 1932.

Art Career

Graduating in the midst of the Depression, Krasner worked a series of jobs as a waiter, a hat decorator, and a factory worker before acquiring a job with the Works Projects Administration’s Federal Art Project in 1934. The project employed artists to teach art, illustrate textbooks, and create paintings, sculpture, mosaics, and stained glass decorations for public buildings. Krasner held various positions for the project, from illustrating a marine biology textbook to executing murals for public buildings.

In 1937, while employed by the WPA, Krasner sought to continue her artistic training by enrolling in classes with the German expressionist Hans Hofmann. Krasner held a passion for modern art, which she nourished through visits to galleries and museums. Hofmann taught her to feed herself. A virtuoso of Matissian color and Picasso-like planes, Hofmann encouraged Krasner’s move toward abstraction more than any previous teacher.

In the 1940s, Krasner left Hofmann’s studio, enriched by her experience there and ready to progress. She embarked upon a string of group exhibitions in the early 1940s with the American Abstract Artists group. Her first exhibition season culminated in an invitation from John Graham to participate in “American and French Paintings” at the McMillen Gallery in New York. The exhibit proved a watershed for both the art world and for Krasner’s personal world. For the first time in art history, such American “unknowns” as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Lee Krasner hung beside European masters. In addition, for the first time, Krasner met a sober Jackson Pollock. (Technically, Krasner and Pollock had met previously at an Artist Union loft party in 1936, when he made a drunken pass at her.)

Relationship with Pollock

Krasner and Pollock maintained a roller-coaster relationship that began with their involvement in “American and French Paintings” and continued for fourteen years until Pollock’s death in 1956. They shared an intense passion for, and commitment to, art. They also maintained a lifelong mutual respect for each other’s work. However, that is where their similarities end. A fiercely independent and determined woman, Krasner served as the rock that held Pollock, a troubled alcoholic, afloat.

On October 25, 1945, the couple married at the Marble Collegiate Church on Fifth Avenue in New York.

By this time, Krasner had ceased to affiliate herself with Judaism. However, she retained an interest in spirituality throughout her life, which manifests itself in her art. Directly after their marriage, despite abject poverty, Krasner and Pollock purchased a farm in East Hampton at Krasner’s request. She sought to create a safe, serene environment for Pollock in the country where, she felt, he would be less tempted by the urban bars and parties that invite drunkenness. Thus began a period in her life when Krasner’s work and her very being succumbed to the all-encompassing task of managing Jackson Pollock, emotionally and financially. As his friend and companion, Krasner filled Pollock’s life with friends and activities in an attempt to divert him from drinking. As his business manager, Krasner promoted Pollock’s work ceaselessly. She organized meetings with dealers, dinners with critics, and sales to galleries. In the 1950s, as Pollock’s artistic reputation grew, so did his emotional problems. Exhausted by his antics and horrified by his recent public pursuit of adulterous affairs, Krasner decided to travel to Europe in the summer of 1956. For the first time since their marriage, Krasner and Pollock were separated. While she was gone, Pollock, driving drunk, crashed his automobile in the front yard of their farm and died on August 11, 1956.

Later Paintings and Legacy

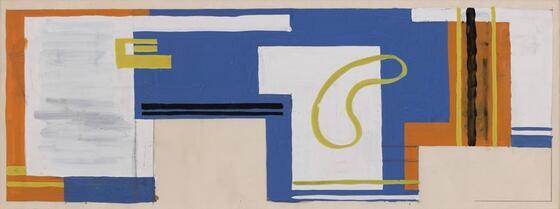

After Pollock’s death, Krasner reclaimed her own life force—painting. As Barbara Rose attests, a Krasner painting defies compartmentalization. Like nature, its essence, color, and rhythm prove organic. Her early work, pre-1956, challenges the perceived physical and mental boundaries of a canvas, using vehicles as varied as mosaic, collage, and image painting. The Little Image series emerged from this period. Several of these allover abstract pattern paintings include calligraphic elements that resemble Hebrew. Krasner recalls painting these images from right to left, just as she was taught to read Hebrew as a little girl. Post-1956, Krasner’s work grew in size and scope. From floral abstractions to turbulent expressions of rage, Krasner’s later canvases breathe color and emotion. In 1965, Krasner received her first retrospective in London at the Whitechapel Gallery.

Following an extended illness, Lee Krasner died on June 20, 1984, at age seventy-six. The first New York retrospective of her work opened at the Museum of Modern Art six months after her death—a long overdue tribute to a pioneer of American abstract art.

Baro, Gene. Lee Krasner: Collages and Works on Paper 1933–1974 (1975).

Campbell, Lawrence. “Of Lilith and Lettuce.” Art News 67 (March 1968): 42+.

Cummings, Paul. A Dictionary of Contemporary American Artists. 2d ed. (1972).

Freed, Hermine Benheim. “Lee Krasner: East Hampton Studio.” Video interview with Lee Krasner [1973?]. Oral History Collection, Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, East Hampton, N.Y..

Friedman, B.H. Jackson Pollock: Energy Made Visible (1972).

Friedman, Sanford. A Haunted Woman (1968).

Gabor, Andrea. Einstein’s Wife: Work and Marriage in the Lives of Five Great Twentieth-Century Women (1995).

Glaser, Bruce. “Jackson Pollock: An Interview with Lee Krasner.” Arts Magazine 41 (April 1967): 36–39.

Guggenheim, Peggy. Confessions of an Art Addict (1960).

Harrison, Helen A. “Artists Find a Special Light on Lee Krasner.” NYTimes, February 15, 1981, 17.

Hobbs, Robert. Lee Krasner (1993).

Howard, Richard. Lee Krasner: Paintings 1959–1962 (1979).

Janis, Sidney. Abstract and Surrealist Art in America (1944).

Kramer, Hilton. “Lee Krasner’s Art—A Harvest of Rhythms.” NYTimes, November 22, 1973, C50.

Naifeh, Steven, and Gregory White Smith. Jackson Pollock: An American Saga (1989).

Nemser, Cindy. “A Conversation with Lee Krasner.” Arts Magazine 47 (April 1973): 43–48.

Obituary. NYTimes, June 21, 1984.

Robertson, Bryan, and B.H. Friedman. Lee Krasner: Paintings, Drawings, and Collages (1965).

Rose, Barbara. Krasner/Pollock: A Working Relationship (1981), and Lee Krasner: A Retrospective (1983), and The Long View. Film (1978) .

Slater, Elinor, and Robert Slater. “Lee Krasner.” Great Jewish Women (1994).

Taylor, Robert. “Lee Krasner: Artist in Her Own Right.” Boston Globe, May 18, 1990, 1.

WWWIA 8.