Hanna Krall

Hanna Krall is one of the most important Polish-Jewish writers and reporters. A Holocaust survivor, she has devoted most of her works to the vicissitudes of other survivors, rescuers, and perpetrators. She combines stories about the Holocaust itself with descriptions of Jewish life in Poland before the destruction. A large number of her informants are “children of the Holocaust,” now adults, who often do not know how they survived or who their parents were. Over the years, Krall developed a unique style characterized by brief, restrained narrative, with a focus on dialogues and monologues of the people about whom she writes, and very little authorial comment. Krall has been internationally recognized and her works have been translated into fourteen languages and adapted for theater and cinema.

Early Life and Education

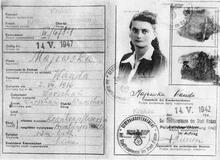

Hanna Krall was born on May 20, 1935 (some sources say 1937), in Warsaw into an assimilated Jewish family. Her parents were Salomon and Felicja Jadwiga (Reichold) Krall. Her father and other relatives perished during the Holocaust, while she and her mother survived with the help of several Christian Poles, moving between the village of Krasnogliny, the city of Warsaw, the little town of Ryki, the Albertine cloister in Życzyn, and other places. By her own account, some 45 people contributed to her survival: “I was handed from one person to another—from Mrs. Pułaska to Mrs. Pomorska, from Mrs. Pomorska to Mrs. Podhorska, from Mrs. Podhorska to Mrs. Jadach. Dr. Tadeusz Stępniewski paid for my expenses from the Polish Resistance funds” (“Gra o moje życie,” My Life at Stake). After the war, she was placed in an orphanage for Jewish children because her mother needed lengthy medical treatment.

In 1955, Krall graduated from the School of Journalism at the University of Warsaw and for a number of years worked as a journalist for major Polish newspapers, including the Warsaw daily Życie Warszawy (1955–1966) and the relatively liberal weekly Polityka (1966–1981). As the latter’s foreign press correspondent, she lived in the Soviet Union from 1966 to 1969; her experiences during that period resulted in three published volumes of journalism. After the introduction of martial law in Poland in 1981, she worked as a freelance writer, contributing periodically to the liberal Catholic weekly Tygodnik Powszechny, and later, after the demise of the Communist regime in Poland in 1989, to the major daily Gazeta Wyborcza, where she worked until 1992 contributing articles and training young reporters. From 1982 to 1987, she also worked for the “Tor” film studio where she collaborated with, among others, the eminent Polish film director Krzysztof Kieślowski. Beginning in 1992, she devoted all her time to writing. She has been married since 1959 to journalist Jerzy Szperkowicz (b. 1933). They have one daughter, Katarzyna.

Reporter and Writer

Krall’s career was launched by her interview with Dr. Marek Edelman (1919-2009), one of the few surviving leaders of the Jewish Fighting Organization in the Warsaw Ghetto. First published in the Wroclaw monthly Odra (1976), it appeared a year later in book form under the title Zdążyć przed Panem Bogiem (first published in English as Shielding the Flame and later as To Outwit God). The work, which focuses on the days of the liquidation of the ghetto, is shocking in its conscious de-heroization of the Jewish revolt, but it simultaneously pays tribute to those who perished in the uprising and reveals their stamina and sacrifice. The book was adapted for the stage and appeared in English under yet another title, To Steal a March on God.

The interview with Edelman was the beginning of a new stage in Krall’s work, to which she has remained faithful ever since. In the books that followed, such as Taniec na cudzym weselu (A Dance at Somebody Else’s Wedding) and Dowody na istnienie (Proofs of Existence), she combines stories about the Holocaust with descriptions of Jewish life in Poland before its destruction, recreating minute details of that existence. In this manner, the stories of destruction become even more real and devastating. A large number of her subjects are “children of the Holocaust,” in their late fifties and sixties in her stories, who often do not know how they survived, who their parents and grandparents were, or what happened to them. Some labored for many years to glean information about their past. Others discovered their origins later in life, while some preferred not to dwell on the past at all. Krall, whose goal is to save these people from oblivion, frequently refers to them as the co-authors of her stories.

As she has mentioned in a number of interviews and on public occasions, Krall fears that a purely historical and statistical approach to the Holocaust focusing on mass murders, deportations, descriptions of death camps, gas chambers, and other atrocities, may arouse only terror and a sense of horror in modern readers rather than evoke compassion, thus possibly even having the reverse effect of what she seeks: causing readers to avoid the topic in the future. Real empathy, according to Krall, is better evoked by recalling individual fates and concentrating on feelings and emotions. In her stories, she writes not only about survivors, but also about their rescuers, informers, and indifferent witnesses, as well as perpetrators.

Krall often focuses on the paradoxical vicissitudes of her characters. Sublokatorka (published in English as Subtenant), is her only novel, first published in Paris in 1985 because of strict censorship in Poland at the time. This is similar to the situation with her novella Okna (Windows), first published in London in 1987 and then reprinted in Warsaw in the same year by an underground press. Krall ironically contrasts the tragic disparity between the Polish and Jewish experience under the German occupation through the symbolic “brightness,” the deaths of Polish resistance fighters, stereotypically perceived as “heroic,” and “darkness,” the equally stereotypical “passive” fate of the Jews in the ghetto.

Themes and Style

Krall’s style is characterized by brief, restrained narrative, with a focus on dialogues and monologues of the people she writes about, and very little authorial comment. Some of her stories resulted from her travels and the people she met on the way, as well as the contacts she established through the network of Jewish survivors and their Christian rescuers; others resulted from her reading of historical works. For example, one of her stories in the volume Tam już nie ma żadnej rzeki (There Is No River There Anymore) was inspired by Christopher Browning’s study Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, about the infamous unit of “ordinary” Germans who massacred tens of thousands of Jews.

In one of her most interesting and meticulously documented works, Wyjątkowo długa linia (An Exceptionally Long Line), Krall is like a detective investigating the fates of people living over the centuries in an almost 500-year-old house in Lublin’s Old Town. Among them was Franciszka Arnsztajnowa, an assimilated Polish-Jewish poet who perished during the Holocaust. The title itself refers to a statement by her friend, the Polish modernist poet Józef Czechowicz who, while parting with her for the last time, claims that nothing will happen to him because he has an exceptionally long lifeline. A few days later, he is killed during bombing of Lublin by Germans in September 1939.

A number of Krall’s stories show how the long silence over Jews in Poland led to the acculturation of survivors who do not even know the basic principles of Jewish tradition and custom, such as the kindling of Sabbath candles or keeping a kosher home. This is even more dramatic among those who discovered their origin as adults, and only then tried to explore their roots by browsing through archival materials, searching for long-lost relatives and developing an interest in Judaism.

Krall might be accused of repeating certain patterns and narrative strategies, as well as overusing a restrained manner of presentation with little authorial comment, but this is her consciously and carefully crafted voice, selected to describe the tragedy of the Holocaust via multiple voices of survivors and witnesses. She compared her approach to putting together a broken jug.

Critics note that her growing use of the fairy tale convention makes some of her stories read like documentary fables. This is apparent both in her creation of the setting (a wood near a shtetl, snow-covered mountains, an old abandoned building) and in her focus on the spiritual and miraculous in the lives of her characters. In her later stories, she often searches for divine intervention and interprets some unbelievable events that befell her protagonists by the presence of the “Grand Scriptwriter,” as she calls him, who creates and controls human fates. The question “Where was God at the time of the Holocaust?” permeates the narrative, but the answer cannot be given.

Compared with other Polish Jewish writers who survived the Holocaust as children (e.g., Henryk Grynberg or Michał Głowiński), Krall avoids writing directly about her war own experience and addresses it only indirectly, referring sometimes to “a little girl with big black eyes.”

Adaptations and Translations

A number of Krall’s works were adapted for theater and cinema. The most notable adaptations were the film by Jan Jakub Kolski titled Daleko od okna (Keep Away from the Window, 2000) on the basis of her story Ta z Hamburga (The Woman from Hamburg). The English version of the story was included in the collection The Woman from Hamburg and Other True Stories, and Dybuk (Dybbuk), the theatrical play by Krzysztof Warlikowski, premiered in 2003, which juxtaposed one of her stories with S. Ansky’s famous drama.

Krall’s work has been highly valued in Poland, receiving many awards such as the underground Solidarity prize and the prize of the Polish PEN Club. In 1998, she received the Award of the Culture Foundation given to outstanding artists and scholars for major achievements and in 2014 the Gloria Artis Gold Medal. In 2017, a monumental edition of her collected works (a volume of more than 1200 pages) was published by Wydawnictwo Literackie (Literary Publishers), a prestigious publishing house in Kraków.

Translated into fourteen languages, her works appear to have gained most recognition in Germany and Sweden. Her limited or lukewarm reception in the United States (only four books published in English) may be due to a general lack of interest in Polish literature or a very different perception of the Holocaust. Last but not least, her elliptic style is very difficult to translate.

Selected Works

Krall, Hanna. “Gra o moje życie.” (My Life at Stake) Polityka 16 (1968): 9. Later included in Bartoszewski, Władysław and Zofia Lewinówna. Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej: Polacy z pomocą Żydom 1939–1945 (He Is from My Home Country: Poles Helping Jews 1939–1945). Kraków: Znak, 1969, p. 411.

Na wschód of Arbatu (East of Arbat). Warsaw: Iskry, 1972.

Syberia, kraj możliwości (Siberia, a Land with Potential) (with Zygmunt Szeliga and Maciej Ilowiecki). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, 1974.

Dojrzałość dostępna dla wszystkich (Maturity Accessible for Everyone). Warsaw: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1977.

Zdążyć przed Panem Bogiem (lit. Make It before God). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1977 (first published in English as Shielding the Flame: An Intimate Conversation with Dr. Marek Edelman, the Last Surviving Leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, trans. by Joanna Stasinska and Lawrence Wechsler. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1986; then as To Outwit God in The Subtenant; To Outwit God, trans. by Jaroslaw Anders. Evanston. Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 1992; and for the third time as To Steal a March on God, trans. by Jadwiga Kosicka, London, New York: Routledge, 1996.

Sześć odcieni bieli (Six Shades of White). Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1978.

Sublokatorka (Subtenant). Paris: Libella, 1985 (published in English as The Subtenant in The Subtenant; To Outwit God, trans. by Jaroslaw Anders. Evanston. Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 1992.

Okna (Windows). London: Aneks, 1987.

Hipnoza (Hypnosis). Warsaw: Alfa, 1989.

Trudności ze wstawaniem (Difficulties in Getting Up). Warsaw: Alfa, 1990.

Taniec na cudzym weselu (A Dance at Somebody Else’s Wedding). Warsaw: Polska Oficyna Wydawnicza BGW, 1993.

Co się stało z naszą bajką (What Happened to Our Fairy Tale). Warsaw: Twój Styl, 1994.

Dowody na istnienie (Proofs of Existence). Poznań: Wydawnictwo a5, 1995.

Tam już nie ma żadnej rzeki (There Is No River There Anymore). Kraków: a5, 1998.

To ty jesteś Daniel (Thou Art Daniel). Kraków: a5, 2001.

Wyjątkowo długa linia (An Exceptionally Long Line). Kraków: a5, 2004.

Spokojne niedzielne popołudnie (A Quiet Sunday Afternoon). Kraków: a5, 2004.

The Woman from Hamburg and Other True Stories. Trans. by Madeline G. Levine. New York: Other Press 2005.

Król kier znów na wylocie (The King of Hearts Is Ready to Leave Again). Warsaw: Świat Książki, 2006 (published in English as Chasing the King of Hearts, trans. Philip Boehm, London: Peirene Press, 2013).

Różowe strusie pióra (Pink Ostrich Feathers). Warsaw: Świat Książki, 2009.

Biała Maria (Maria White). Warsaw: Świat Książki, 2011.

Sześć odcieni bieli i inne historie (Six Shades of White and Other Stories). Warsaw: Dowody na Istnienie Wydawnictwo, cop., 2015.

Fantom bólu: Reportaże wszystkie (The Phantom of Pain: Collected Works). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2017.

Pola i inne rzeczy teatralne (Pola and Other Theatrical Things). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2017.

Synapsy Marii H. (Synapses of Maria H.). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2020.

Antczak, Jacek. Reporterka: Rozmowy z Hanną Krall (The Reporter: Conversations with Hanna Krall). Warsaw, Agora, 2015.

Backer, Paul. Review of To Steal a March on God by Hanna Krall. Slavic and East European Journal 4 (1997): 710–712.

Breysach, Barbara. “Hanna Krall’s Early Autobiographical Writing in the Context of Polish-Jewish Relations,” Yearbook for European Jewish Literature Studies 1. Berlin: De Gruyer, 2014.

Dawidowicz, Lucy S. “The Curious Case of Marek Edelman.” Commentary 3 (March 1987): 66–69.

“Hanny Krall dowiadywanie się świata” (Hanna Krall Is Learning about the World). An interview with Katarzyna Janowska and Witold Bereś, Kontrapunkt, Magazyn Kulturalny Tygodnika Powszechnego (April 28, 1996): i-iii.

Kot, Wiesław. Hanna Krall. Poznań: Dom Wydawniczy Rebis, 2000.

Polonsky, Antony, and Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska. Contemporary Jewish Writing in Poland: An Anthology. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

Tochman, Wojciech. Krall. Warsaw: Fundacja Instytutu Reportażu 2015.

Wróbel, Józef. Tematy żydowskie w prozie polskiej 1939–1987 (Jewish Themes in Polish Prose: 1939–1987). Kraków: Tow. Autorów i Wydawców Prac Naukowych "Universitas," 1991.