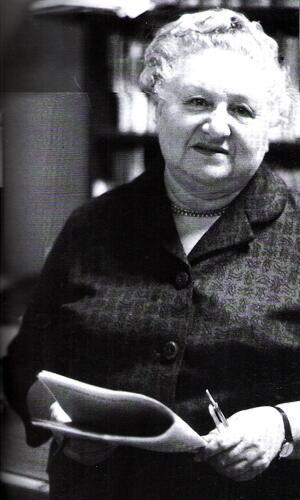

Fanny Klenerman

Fanny Klenerman, born in Belarus in 1897, immigrated to South Africa as a child. Throughout her life, she was deeply involved in political and labor activism. She was a member first of the Labour Party, then the Communist Party of South Africa, and later the Workers Party of South Africa. In 1925, she founded the South African Women's Workers' Union, and she later worked with other unions. In 1931, she took over her husband’s bookshop and renamed it the Vanguard Bookshop. A hub for radical political thought and literature in Johannesburg, the bookshop became famous for introducing banned works like James Joyce's Ulysses and for fostering anti-apartheid activism, though Klenerman faced financial struggles that eventually led to the shop's closure in 1974.

A lifelong rebel, a trade unionist, and a Trotskyite, Fanny Klenerman is chiefly associated with the Vanguard bookshop, an icon in left-wing circles in Johannesburg, South Africa, during the period 1931 to 1974.

Childhood and Education

Born in 1897 in Lutzin in the Vitebsk Province in Belorus (today Ludza, Latgale Province, Latvia), Fanny Klenerman immigrated to South Africa at the age of four or five, together with her mother and older brother. They joined her father, who had originally immigrated to Johannesburg in the late 1890s. After the South African war (1899-1902), her father moved the family to Kimberley in the Northern Cape, where he had opened a men’s clothing store. Self-educated and an accomplished Hebrew scholar, her father lost his religion but not his Jewish identity. Although the family never belonged to a synagogue, Fanny’s mother insisted that they attend services on the High Holidays (New Year and the Day of Atonement), so that the children should not “grow up to be savages” (Klenerman manuscript). The family supported Jewish organizations but were not Zionists.

Klenerman spoke Yiddish as a child and started school in Kimberley not knowing a word of English. She soon picked it up, though, and by the age of seven or eight was an avid reader. She was first exposed to socialist ideas by her father, who imported The Clarion and other liberal and socialist newspapers from Britain. He and his friends were dedicated to socialism and to changing society, and they discussed these matters with Fanny while she was still in high school. By the age of fifteen she was an accomplished public speaker. At the University of Cape Town, where she graduated with a degree in English and History, she was a prominent speaker in the Students’ Parliament, and her interest in socialism was encouraged by reading The New Age, the New York Socialist weekly.

Political and Labor Union Involvement

After graduating, Klenerman taught at Wynberg Girls School in Cape Town but found the atmosphere “stuffy and repressive” (Berger). She returned home to Kimberley, where she was unable to find work because of her outspoken political views, expressed in letters to the local newspapers. Shortly after the Rand revolt in 1922, a strike of white mineworkers in reaction to a decrease in the price of gold and mine bosses giving jobs to lower-paid Black workers, she left to work for the Labour Party in Johannesburg, relying on her father’s connections. Within a year, she broke with the Party, objecting to its industrial colour bar, which prevented non-whites from holding certain jobs. Many years later she recalled: “Here we’ve come to a country the British stole from the Africans… They haven’t got money to go anywhere, and you’re excluding them from society and bringing them down to the level of serfs. And I said ‘I can’t take it.’”

Klenerman joined the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), the only multi-racial party at the time. She distributed Umsebenzi (The Worker) newspaper in Rooiyard in Soweto, the African suburb of Johannesburg, every Friday afternoon. When she was expelled in 1935 for being critical of CPSA policy, she joined the Workers Party of South Africa, founded that year in Cape Town by the Lenin Club and inspired by the literature of Leon Trotsky. A branch was established in Johannesburg with a small but very active membership.

After the 1922 Rand strike, with the Trade Union movement in chaos, Klenerman determined to form a union to enable women to fight for higher wages. Despite strong resistance from factory owners, in 1925 she succeeded in forming the South African Women’s Workers’ Union, which managed to get women’s wages increased but quickly split into a Sweet Makers Union and a Waitresses Union. After a few years, the Union was absorbed by a larger union.

Klenerman subsequently worked for the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Unions (ICU) teaching English to Africans who had not had any education. Between 1935 and 1940, she also taught English to Africans at a night school associated with the union of Max Gordon, a fellow Trotskyite, who in 1939 had eleven unions representing 20,000 workers from the Joint Committee of African Workers. These classes ended in 1940 when Gordon was interned for opposing the war, and the committee collapsed along with his unions.

Marriage to Frank Glass

In January 1927, Klenerman married Frank Glass, a talented speaker and a journalist who was working as the Secretary of the Tailors’ Union. About a year into their marriage, Glass was obliged to resign from the Union for unknown reason, and as a result, Klenerman also resigned from her Union. With Russian Jewish immigrants streaming into South Africa, Klenerman began giving private English lessons as well as organizing classes at the Jewish Workers’ Club.

Besides his journalistic work, Glass also ran a bookshop named Frank Glass Booksellers. Klenerman was an omnivorous reader, mostly of American books on politics. She wished to establish a depot in South Africa to distribute some of the political writings from the United States. One of the publications they ordered, The New Masses (1926-1948), the principal cultural organ of the American Left from 1929 onwards, attracted growing numbers of subscribers.

Glass was appointed as a bookkeeper at the ICU. When this work came to an end, Klenerman and Glass took over a tearoom in a working-class district that soon closed down. Their financial difficulties put a strain on their marriage and Glass decided to travel to China to continue his political work. In 1941, he settled in Los Angeles. Fanny met Joe Moed, a Belgian national, who became her partner in life as well as in the bookshop

The Vanguard Bookshop

When Glass decided to travel to China, Klenerman took over Frank Glass Booksellers and renamed it the Vanguard Bookshop, after the Vanguard Press (1926-1988), an American left-wing publishing house that published an array of books on radical topics. The new bookshop opened on April 17, 1931, in Hatfield House in Eloff Street.

Klenerman acquired a reputation as a discerning bookseller. She stocked European classics, such as Chekhov, Strindberg, and Mann. Guided by magazines, such as the aforementioned New Masses, she introduced books that might otherwise never have reached South Africa. She also subscribed to a few Soviet newspapers, the English-language Moscow News, and small numbers of the Russian-language newspapers Izvestia (Star), Pravda (Truth), and Novi Mir (The New World), the latter a monthly that included literature, literary opinion, and philosophy. Klenerman introduced the books of the Left Book Club published by Victor Gollancz, a British publisher, writer and humanitarian who championed causes such as socialism and pacifism. Together with a few others, she organized a Left Book Club discussion group for several years.

One of Klenerman’s greatest triumphs was the introduction of James Joyce’s Ulysees into South Africa, despite the fact that it was widely banned. Her bookshop became well known all over Johannesburg and drew numerous customers to its one room on the second floor of Hatfield House. Writes Baruch Hirson: “This was more than a shop—it was a forum for informed political ideas, and also for the latest currents in philosophy, literature and art.”

While most of the shop’s customers were white, it employed Black shelvers, some of whom found a niche in journalism in the post-war years with journals like Drum. Another Black shelver, Todd Matshikiza, wrote the lyrics for the landmark South African musical show King Kong (1959), and Bloke Modisane wrote Blame Me on History, published in 1987 after he left South Africa. Klenerman also employed anti-Apartheid political activists who were banned but allowed to work.

As her stock grew, Klenerman’s biggest problem was premises. She moved from the Hatfield location to Warwick House at 51 Von Brandis Street (1939-1952) to Commissioner Street (1966-1974), where the shop remained until forced by the building’s owners to close down in 1974 because Klenerman could no longer pay the rent. The last shop location was on two levels, requiring many more staff. Klenerman was uncomfortable with her position, as she felt that to be a socialist and a boss was a contradiction in terms.

Conclusion

Fanny Klenerman contributed to many causes. She was a trade union organizer, founder of the South African Women Workers’ trade union. She taught English to Africans in the night schools organized by the Unions. She ran a bookshop that was unmatched in South Africa.

In 1982, at the age of 85, just a year before her death, Klenerman dictated her story on to audiotape. In 1988, the tapes and their transcription were donated to the Department of Historical Papers at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Belling, Veronica. “”More than a bookshop:: Fanny Klenerman and the Vanguard bookshop, 1931-1974.” Jewish Affairs, 72, 1 (Spring 2017): 15-22.

Berger, Iris. Threads of Solidarity: Women in South African Industry, 1900-1980. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Hirson, Baruch. “Death of a Revolutionary: Frank Glass/ Li Fu-Jen/John Lang 1901-1988,” The Searchlight South Africa, 1, 1 (September 1988): 36-39.

Klenerman manuscript, Fanny Klenerman papers, 2103, Department of Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand.