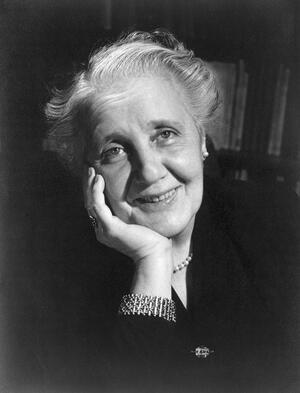

Melanie Klein

Child psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, c. 1952. This file comes from Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom. Refer to Wellcome blog post (archive).

Born in Vienna in 1882 into an assimilated Jewish family, Melanie Klein was pioneer in the field of child psychoanalysis. Her early life was marked by tragedy, including the deaths of her father and two of her siblings. In 1903, she married Arthur Klein, a chemical engineer, and they had three children. They moved to Budapest in 1910, where Klein, entered into analysis with Sándor Ferenczi, a colleague of Sigmund Freud, who encouraged her to become a child analyst. Separating from her husband, she moved to Berlin in 1921 and entered analysis with Karl Abraham. She left Berlin for London in 1926 where she achieved success and recognition, although the arrival of Anna Freud in 1939 challenged her position. Klein died in London in 1960.

Melanie Klein made an original and significant contribution to twentieth-century psychoanalysis through a collection of papers published between 1921 and 1963. She was a pioneer of child psychoanalysis, the inventor of the “play technique” that enables children to express themselves through the use of toys, the founder of the British “object relations” school of psychoanalysis that understands psyche as developing in relation to external objects, and an early theoretician of emotions and their significance in human development. She was the first analyst to focus on the role of the mother in the early development of the infant and a reformer of the psychoanalysis of individuals with psychotic and borderline conditions.

Family and Childhood

A photograph of Melanie Klein in 1890. Klein would go on to be a pioneer in child psychology. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Klein was born on March 30, 1882, in Vienna, the fourth and youngest child of Moriz Reizes (1828–1900), a doctor from Lemberg, Galicia, and his wife, Libussa Deutsch Reizes (1852–1914), a well-educated woman from a Slovakian Jewish family twenty-four years his junior. Moriz Reizes came from an orthodox Jewish background, and in keeping with his parents’ wishes, initially devoted his life to Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmudic study. He later rebelled and trained to be a doctor, choosing science over religion in a move that was to influence his daughter. She aspired to study medicine with a specialty in psychiatry and adopted her father’s preference for scientific rationality over religious dogma. Thus, in her first published work, Klein argued that parents should explain worldly realities, including those of sexual reproduction, to the young child rather than use religious coercion as a method of discipline.

Moriz Reizes’s parents deeply disapproved of his career move, which they regarded as a betrayal of his religious roots. When he was sitting for his medical exams, his mother prayed for him to fail. This painful start to his professional life was followed by further disappointments. He struggled to make his way as a doctor, serving as a medical consultant in a music hall, and was forced to take on dental work to supplement his income. Libussa was obliged to keep a shop where she sold plants and reptiles to help with the family’s economic difficulties. The stress experienced by the family compounded a tragic bereavement in 1886. Melanie was four years old when her eight-year-old sister Sidonie died from scrofula, a form of tuberculosis. The experience of loss and mourning re-surfaced in Klein’s life several times and became a central theme in her theory of development.

Klein’s feelings about Judaism were ambivalent. In her autobiography, she expressed admiration for her father’s independent streak and disdain for the Yiddish-speaking members of her family. Religion did not play a significant role in her family life, though she recalled celebrating A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover and the Day of Atonement and feeling marginalized as a Jew in Catholic Vienna. After her marriage, she and her husband converted to Christianity, joining the Unitarian Church because they felt more comfortable with its rejection of the dogma of the Holy Trinity, and had all of their children baptized. Although Klein proclaimed to have no religious beliefs, she affirmed her Jewish origins and felt, like Sigmund Freud, that her strength to pursue her scientific work in the face of opposition derived in part from her minority status as a Jew.

Marriage and Children

In 1900, when Klein was eighteen, her father died of pneumonia. Two years later, her 25-year-old brother Emanuel, to whom she was especially close, died from heart failure, throwing the family into further sadness and hardship. Rather than realizing her wish for medical training, she settled for the more realistic option of marriage. In 1903, a year after her brother’s death, she married Arthur Klein, a second cousin on her mother’s side, a chemical engineer with whom she had three children, Melitta [Schmideberg] in 1904, Hans in 1907, and Erich [Eric Clyne] in 1914.

The family settled in Rosenberg, a small town in Hungary, where Arthur’s father managed a bank and served as a mayor and senator. However, circumstances soon placed strains on the relationship, and the marriage was unhappy. Arthur needed to be relocated as part of his career, and the couple was obliged to move several times. During her young married life, Klein led a rootless, socially isolated existence in small, provincial places, which took its toll in the form of depression. Her marriage was also not developing into the kind of close, sustaining bond that she longed for.

Early Experience with Analysis

Things took a turn for the better in 1910 when the Kleins moved to the much more cosmopolitan Budapest, and Klein sought help for her demoralized state. Through his business dealings, Arthur met the Ferenczi family, and around 1912 Melanie entered analysis with Sándor Ferenczi (1873–1933), a lively and insightful adherent of Freud. In the year 1914, the same year that her son Erich was born, Klein’s mother died, intensifying her depression. Klein knew nothing about psychoanalysis, but the process exerted an immediate fascination on her powerful but starved intellect. She supplemented her sessions with reading, particularly Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams.

Himself interested in the potential that psychoanalysis held for the treatment of children, Ferenczi tried to promote a similar interest in his women patients, and Klein felt particularly encouraged by him. In 1919 she wrote up the events of a four-month period in the life of her five-year-old son Erich, when he became interested in the biological origins of life, and she could enlighten him along Freudian psychoanalytic concepts. Klein presented the paper to the Budapest Psychoanalytic Society as a prelude to becoming a member. Comments on the paper led her to continue her work with Erich, pursuing a more structured analysis which already drew on his use of play to interpret his mental states. This was published in 1921 as the case study of “Fritz” and launched her career as a child psychoanalyst.

Move to Berlin

Rising antisemitism and political turmoil in postwar Budapest weakened the Hungarian psychoanalytic movement and made Budapest less hospitable for Jews. Arthur left for Sweden around 1919, and Melanie and her three children went to stay with her in-laws. In 1921, Klein moved to Berlin, a center of culture and psychoanalysis, with her son Erich. She joined the Berlin Psychoanalytic Society in 1922, the same year that Anna Freud became a member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. While in Berlin, Klein entered her second psychoanalysis with Karl Abraham (1877–1925), head of the Berlin Psychoanalytical Society, who would become her mentor and protector. She began to treat children, provided them with toys, and argued that, like Freud’s dreams, children’s play was a “royal road to the unconscious.” The Berlin Society was taken aback by her work, especially as it portrayed the child in a new and unusual light.

Klein gave her child patients the same privacy and freedom that was normally granted to adults. They were seen away from their parents and encouraged to play freely without instructions or exhortations. She then interpreted the unconscious experience conveyed in the play. It was the first time that children were provided with a private space of this kind, and her little patients were able to make use of it and spontaneously reveal their inner selves. Klein discovered that given such conditions, her child-patients often expressed extreme feelings of anxiety and aggression. She concluded that young children are at the mercy of acute emotional and instinctual fluctuations and that they rely on adults for the regulation of their emotional states.

This raw picture of childhood unsettled the Berlin psychoanalysts, but Karl Abraham protected Klein’s situation by virtue of his position. However, Abraham died unexpectedly after a brief illness in 1925 shortly after Klein divorced Arthur, and her position in Berlin became difficult, with overt opposition to her work. By this stage, she had become known in London and was invited by Ernest Jones to move there in 1926.

Success and Conflict in London

In London, Klein initially found a very congenial professional climate. She developed innovative concepts based on her experience with children, and these began to assume the outlines of a new theory. At its heart was a vision of the infant as an innately social being, born with a capacity to relate by seeking and responding to human contact. The infant is able to “recognize” the mother, but this recognition is initially partial and piecemeal, centered on experiences of fulfillment or frustration at the mother’s feeding breast. The infant reacts powerfully to satisfaction and frustration, responding to worldly situations with the natural emotional equipment of love and hate.

Klein argued that the most disturbing emotion for the infant is anxiety, which is aroused by frustration and undermines security. The infant thus develops primitive defense mechanisms, which are deployed until the maturation process develops the mind’s ability to integrate different experiences of the mother and accommodate her as a more fully understood, “whole” being. Klein ultimately designated this process as a shift from a “paranoid-schizoid position” to a “depressive position.” She believed that the dual forces of love and hate continue to war in the human heart throughout development. A happy individual learns to reconcile these forces by subsuming the hated flaws and frustrating absences of the mother in an overall love for her. When the mother is internalized in the psyche as a whole “good object,” the foundation for security is laid, reconciling an imperfect mother and an imperfect world. Thus a balanced adult is able to manage worldly frustrations without becoming regularly overwhelmed by aggression and anxiety.

The years between 1926 through 1938 were Klein’s most productive. In 1927, she was elected a member of the British Psychoanalytic Society, and in 1932, she published her first major theoretical work, The Psycho-Analysis of Children. However, she also suffered a series of emotional setbacks. In 1933, her daughter Melitta, also a psychoanalyst, began to attack her ideas, and Klein’s Berlin lover, Chezkel Zvi Kloetzel, left for Palestine. In 1934, her son Hans died in a hiking accident in the Tatra Mountains. Klein was too devastated to attend the funeral.

Towards the 1940s, Klein’s professional situation in the British Psychoanalytic Society deteriorated. After Germany’s invasion of Austria in 1938, Freud and his daughter Anna fled Europe and came to settle in London, where Jewish refugees encountered British antisemitism and were designated enemy aliens. Tensions and hostility between Jewish refugees and those already in the United Kingdom ensued. Trained as a teacher and more didactic in her approach, Anna Freud had already developed her own brand of child psychoanalysis, which seemed more in line with Freud’s thinking than Klein’s. Both of their theories had relevance beyond child psychoanalysis and implications for psychoanalysis as a whole. In London, Anna Freud questioned the status of Klein’s ideas, and the tension between them increased.

This tension culminated in the “Extraordinary Meetings” and the “Controversial Discussions,” a series of heated exchanges between Kleinians and Freudians between 1942 and 1944. Klein and her adherents were requested to make presentations of their key ideas to the British Psychoanalytic Society in its scientific meetings, so that these could be debated. One of the painful features of this period for Klein was that her daughter joined the non-Kleinian camp in a public display of opposition. Their personal relationship was also at an end. The controversial discussions were extensive, yet no theoretical conclusions could be unanimously reached. A compromise resulted in the division of the British Psychoanalytic Society into three schools of thought: Freudian, Kleinian, and Independent.

Influence and Death

After the controversial discussions, Klein’s position stabilized, and up to the time of her death she continued to develop her ideas. She focused on the earliest months of life and also wrote her most controversial paper, in which she argued that envy is a destructive emotion, which is an inevitable feature of human development and relationships. Towards the end of her life, she tried to rekindle her Jewish faith and called for a rabbi, but then changed her mind, attributing it to a sentimental whim.

Klein died in London on September 22,1960, at the age of 78 of colon cancer and anemia; she was surrounded to the end by a small but loyal collegial group. By this time, she had influenced some of the most significant thinkers on early development including Donald Winnicott (1896–1971), John Bowlby (1907–1990), and Wilfred Bion (1897–1979). Her model of child psychoanalysis proved to be of lasting value. Her ideas on anxieties and defenses and the theoretical concepts that she developed on their basis influenced significant developments in twentieth-century psychoanalytic technique.

Selected Works

The Psycho-Analysis of Children. London: Hogarth Press, 1932.

Love, Guilt and Reparation and other works 1921-1945. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1975.

Envy and Gratitude and other works, 1946-1963. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis. 1975.

Narrative of a Child Analysis. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1961.

Bocossa, Julia, Catalina Bronstein, Claire Pajaczkowsky, eds. The New Klein—Lacan Dialogues. London: Routledge, 2015.

Britzman, Deborah. After Education: Anna Freud, Melanie Klein, and Psychoanalytic Histories of Learning. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2003.

Britzman, Deborah. Melanie Klein: Early Analysis, Play, and the Question of Freedom. London: Springer, 2016.

Grosskurth, Phyllis. Melanie Klein: Her World and her Work. New York: Aronson, 1986.

Hinshelwood, R.D. A Dictionary of Kleinian Thought. London: Free Association Books, 1989.

King, Pearl and Riccardo Steiner, eds. The Freud-Klein Controversies 1941–45. London and New York: Routledge, 1991.

Kristeva, Julia. Melanie Klein. Trans. by Ross Guberman. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

Likierman, Meira. Melanie Klein: Her Work in Context. London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2001.

Melanie Klein Trust. https://melanie-klein-trust.org.uk/

Segal, Julia. Melanie Klein, second edition. London: SAGE Publications, 2004.

Spillius, Elizabeth Bott. Melanie Klein Today. Vols. I & II, London: Routledge, 1988.