Jezebel: Bible

Jezebel was a Phoenician royal whose identity and name have come to signify a power-hungry, violent, and whorish woman. A follower of Baal, she promises to kill the prophet Elijah, who flees when hearing her plan. She also manipulates many powerful men around her in a story about land ownership, leading to the death of several men. Jezebel is ultimately murdered by palace officials, and she is referenced consistently in biblical texts as the epitome of an evil, non-believing female. However, her narrative shows that she wielded significant power and was one of few women to do so in the Bible, and resentment of her can be at least partially attributed to the general scriptural dislike of powerful women.

Genealogy and Position of Power

Jezebel was the daughter of Ethbaal, king of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre, and wife of Ahab, king of Israel (1 Kgs 16:31), in the mid-ninth century BCE. She was undoubtedly the chief wife of Ahab and co-ruler with him. It is implied that she was the mother of Ahab’s son and successor Ahaziah (1 Kgs 22:53) and alternately implied and stated that she was mother of the next king, Jehoram (2 Kgs 3:2, 13; 9:22). Ahab had other unnamed wives as well and many unnamed sons (1 Kgs 20:3, 5, 7; 2 Kings 10). Hence, whether Jezebel had other children or, specifically, was Athaliah’s mother is unclear.

The extent of Jezebel’s power is evidenced by the necessity for Jehu, the founder of the next royal dynasty in Israel, to murder her before his rule can be established (2 Kgs 9:30–37)—even though her royal husband and sons are by now dead. The biblical text insists that she is evil through and through.

Jezebel is the enemy of YHWH’s prophets: she “killed the prophets of the Lord” (1 Kgs 18:13). On the other hand, there are “the four hundred fifty prophets of Baal and the four hundred prophets of Asherah, who eat at Jezebel’s table” (v. 19). Elijah kills Jezebel’s prophets on Mount Carmel (chap. 18). As a result, she swears that she will kill him (19:3). He takes her threat seriously and flees to the south, beyond the Israelite territory. His fleeing indicates Jezebel’s power in the realm.

Story of Naboth and Death

Another indication of her power is the story of Naboth (1 Kings 21). Ahab wishes to buy Naboth’s vineyard, which is adjacent to the royal complex in Jezreel. Naboth refuses to give or sell it, claiming its status as nontransferable ancestral land. Ahab is depressed by this but cannot do anything. Jezebel, who sees the matter as a test case of monarchic power (v. 7), finds a way: she writes to the elders and dignitaries of Jezreel, asking them to bring two false witnesses to claim that Naboth has cursed the king and God. Such behavior signifies treason; Naboth is stoned to death, and his property reverts to the king.

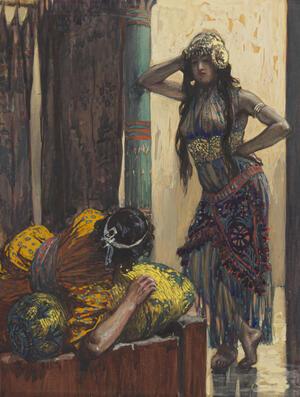

Although the letter is ostensibly signed with the king’s seal (v. 8), the report comes back to Jezebel (v. 14). She tells Ahab that he can inherit Naboth’s land, and he does so. Elijah protests to Ahab, “Thus says the Lord: Have you killed, and also taken possession?” (v. 19); he prophesies that Ahab’s male descendants will die prematurely, his dynasty will perish, and that the “dogs shall eat Jezebel within the bounds of Jezreel” (v. 23). Ahab dies a brave soldier’s death in Samaria (1 Kings 22); his son and Jezebel’s, Ahaziah, succeeds to the throne for two years and then dies. His brother Jehoram succeeds him and is killed by Jehu, the new contender for the throne (2 Kings 9). Jezebel is killed by Jehu as well (2 Kgs 9:31–37): as she regally awaits Jehu and her doom in the Jezreel palace, some palace officials drop her through the lattice window. By the time Jehu has finished eating and orders that she be buried “for she is a king’s daughter” (2 Kgs 9:34), the dogs have already eaten most of her carcass—in keeping with Elijah’s prophecy.

Legacy and Significance

Jezebel is characterized as totally evil in the biblical text and beyond it: in the New Testament her name is a generic catchword for a whoring, non-believing female adversary (Rev 2:20); in Judeo-Christian traditions, she is evil incarnate (see Pippin). The Bible is careful not to refer to her as queen. And yet, this is precisely what she seems to have been. Some early Jewish, albeit postbiblical, sources deconstruct the general picture: “Four women exercised government in the world: Jezebel and Athaliah from Israel, Semiramis and Vashti from the [gentile] nations” (in a Jewish A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash for the Book of Esther, Esther Rabbah). Clearly, Jezebel acted as queen even though the Bible itself refuses her the title and its attendant respect, not to mention approval.

In the biblical text, as Trible notes, Jezebel is contrasted with and juxtaposed to the prophet Elijah, to the extent that they both form the two panels of a mirrored diptych. She is a Baal supporter, he is a YHWH supporter; she is a woman, he is a man; she is a foreigner, he is a native; she has monarchic power, he has prophetic power; she threatens, he flees; finally, he wins, she is liquidated. The real conflict is not between Ahab (the king) and Elijah, but between Jezebel (the queen in actuality, if not in title) and Elijah. Ultimately the forces of YHWH win; Jezebel loses. It remains to be understood why she gets such bad press.

It seems reasonable that Jezebel, a foreign royal princess by birth, was highly educated and efficient. Also, although her son’s theophoric names have the element yah or yahu (referring to YHWH) in them, she seems to have been a patron and devotee of the Baal cult. It is not incomprehensible that, whereas Ahab devoted himself to military and foreign affairs, Jezebel acted as his deputy for internal affairs: the Naboth report comes back to her, as if the king’s seal was hers (see Avigad’s identification of a seal, “lyzbl,” as possibly Jezebel’s); she has her own “table,” that is her own economic establishment and budget; she has her own “prophets,” probably a religious establishment that she controls. All these point toward an official or semiofficial position that Jezebel held by virtue of her character, her royal origin and connections, her husband’s and later her children’s esteem, and her religious affiliation to the Baal (possibly also Asherah) cult. Perhaps she had the status of gebira “queen mother” (Ben-Barak), or of “co-regent” (Brenner).

At any rate, there is no doubt that the biblical and later accounts distort her portrait for several reasons, among which we can list her monarchic power, deemed unfit in a woman; her reported devotion to the Baal and Asherah cult and her objection to Elijah and other prophets of YHWH; her education and legal know-how (shown in the Naboth affair); and her foreign origin. Ultimately, the same passages that disclaim Jezebel as evil, “whoring,” and immoral are witness to her power and the need to curb it.

Avigad, Nahman. “The Seal of Jezebel.” Israel Exploration Journal 14 (1964): 274–276.

Ben-Barak, Zafrira. “The Status and Right of the Gebira.” Journal of Biblical Literature 110 (1991): 23–34.

Brenner, Athalya. The Israelite Woman: Social Role and Literary Type in Biblical Narrative. Sheffield, England: 1985.

Brewer-Boydston, Ginny. “Good Queen Mothers, Bad Queen Mothers: The Theological Presentation of the Queen Mother in 1 and 2 Kings.” Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 54. Washington, DC: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 2016.

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. “Jezebel, or Deuteronomy's Worst Nightmare.” In Reading the Women of the Bible, 211-214.

Kalmanofsky, Amy. “Jezebel and Ahab.” In Gender Play in the Hebrew Bible, 95-113. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Meyers, Carol, General Editor. Women in Scripture. New York: 2000.

Pippin, Tina. “Jezebel Re-Vamped.” In A Feminist Companion to Samuel and Kings, edited by Athalya Brenner, 196–206. Sheffield, England: 1994.

Seeman, Don. “The Watcher at the Window: Cultural Poetics of a Biblical Motif.” Prooftexts 24 (2004): 1-50.

References the motif of ‘the woman in the window’; biblical examples include Michal, Rahab, and the mother of Sisera.

Trible, Phyllis. “The Odd Couple: Elijah and Jezebel.” In Out of the Garden: Women Writers on the Bible, edited by Christine Büchmann and Celina Spiegel, 166–179, 340–341. New York: 1994.