Women’s Service in the Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces is among the few armies that conscript women under a mandatory military draft law. Women have served in the IDF since its establishment in 1948; their integration has been shaped by the perception of the IDF as a people’s army, security needs, and social processes that contribute to or undermine gender equality. At first women were allowed to serve only in the “feminine” roles of office workers, nurses, and teachers. New roles were opened to them after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, but mostly in order to free men for combat. In the Alice Miller Case in 1995, however, the High Court of Justice ruled that women had the right to equality in their military service, both formally and on the ground. Still, today women make up only about 40% of conscript soldiers and 25% of the office corps.

Introduction

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) is among the only armies in the world that conscript women into its ranks under a mandatory military draft law. As of 2021, women make up about 40% of the IDF's conscript soldiers and about 25% of the officer corps. In 2018, about 10,000 women served in the IDF in permanent service. Despite the “mandatory” nature of the draft law, the average rate of enlistment in recent years has been 58% for women, quite low compared to the average enlistment rate of men, which stands at about 75% of the total possible conscription.

Women have served in the IDF since its establishment in 1948, and the Women's Corps was founded on May 16, 1948, by women officers who had served in the British army. In 1949, women’s service was anchored in the Security Service Law of 5749/1949. The Security Service Law stipulates that anyone, male or female, who is an Israeli citizen or a permanent resident who has reached the age of 18 and who has not been exempted from service is an "army veteran," meaning he or she could be called up for conscription. At the time of its enactment, the law defined a service period of 30 months for men and eighteen months for women. The law also stipulates that women can apply for discharge from the army for religious and conscientious reasons, as well as for three additional reasons: parenting, marriage, and pregnancy.

Three main factors have shaped the integration of women into the IDF throughout the years: 1. The perception of the IDF as a people’s army; 2. Security needs; and 3. Social processes that contribute to or undermine gender equality.

Women’s Conscription as an Obvious Matter

In October 1949, approximately a year and a half after the establishment of the State of Israel, the Institute for Applied Social Research conducted a poll asking the public whether it was in favor of equal rights for women, and indeed 92% were in favor. However, opinions were divided on the question of whether women should be drafted during peacetime (in other words, whether there should be mandatory conscription for women): 52.5% were in favor and 47.5% were opposed. Israel’s leaders, including David Ben-Gurion, were unequivocal in this regard: Ben-Gurion believed that the state should both demand as much from women as from men and grant them equal rights (State of Israel, Public Opinion on Drafting Women into the Army).

Despite Ben-Gurion’s firm stance regarding gender equality, at first women were allowed to serve in the army only as office workers, nurses, and teachers—positions traditionally perceived as feminine roles. Notwithstanding this inherent discrimination, in the early days the sense of mission and the motivation of soldiers in the Women’s Corps were relatively high—as demonstrated, for example, by the poll conducted in September 1948 in the Women’s Corps Battalion 205, whose findings indicated that 93% of women soldiers reported being proud to belong to the Women’s Corps.

Whether women had served in combat roles even before the establishment of the IDF, and if so what the scope of their service was, is unclear. Researcher Lilach Rosenberg-Friedman claims that the reality was far from the myth. Although the Palmah trained women to fight, when put to the test the traditional perception of women only as supporters of war prevailed; within a month of the beginning of the War of Independence, all women fighters were transferred to the home front, and only a few who had distinct professional abilities remained in their positions (Busidan).

Indeed, after the War of Independence and against the background of the capture of women by the enemy (about a hundred women were captured, according to Rosenberg-Friedman), the Defense Service Law established three categories of roles that would not be assigned to women: professions that require physical abilities, professions in which the conditions of service are not suitable for women, and combat roles.

Thus, in practice the Women's Corps established women's service as an integral part of the Israel Defense Forces but defined a clear gender division between male and female roles: unlike men, who were assigned to combat roles, women were recruited mainly to support soldiers and to leave operational positions to men. As Karin Carmit Yefet and Shulamit Almog concluded: "The IDF first generation is an army of men as servants of the people, and of women as servants of men” (Yefet and Almog).

Expanding Women’s Army Service

The view according to which women belonged on the home front and men on the front lines also prevailed after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, a time of pronounced gender inequality, despite the fact that a woman, Golda Meir, was serving as prime minister at the time. During this time, women were excluded from playing a part in the three primary tasks of warfare: military defense, civil administration, and military production (Lachover). After the war, due to the need to build up its troops, the army adopted a new and expanded policy regarding women’s placement in military roles, enabling women to be trained for roles that, until then, had been open only to men. The opening of these new roles was based on the view that drafting women would free men from positions on the home front, enabling them to participate in combat, and so most of the training effort was directed at positions such as instructors, drivers, aircraft mechanics, and communication jobs.

Nevertheless, some far-reaching measures were taken during those years regarding women’s military service, such as lifting the restrictions that had previously existed on women’s presence in combat areas, particularly outside Israel’s borders (1982) and removing the section of the Defense Service Law that listed the positions and roles closed to women (1987).

From the day the IDF was established until the 1990s, then, commitment to women’s equality was expressed mainly in the mandatory military draft for women and the anchoring of their conscription in law. But regarding integrating them into units and the scope of positions open to them, the needs of the hour along with gender stereotypes regarding “feminine” roles dictated the reality on the ground.

The Turning Point: The Alice Miller Case

For the most part, the IDF’s approach to women’s service can be divided into two periods: before the Alice Miller case (1995)—or more precisely, before the Defense Service Law was amended in 2000 following the High Court of Justice’s ruling on the case—and afterward. The significant difference between these two periods does not lie in the number of units opened to women—a process that was accelerated once the ruling was issued—nor in the percentage of women who enlisted, which actually decreased. Rather, what changed was the motivation for integrating women into army units and the principle underlying women’s integration into the IDF and utilizing their potential to the maximum.

Alice Miller submitted her petition to the High Court of Justice when the army rejected her as a candidate for the pilots’ course because of her gender. The High Court of Justice ruled that women had the right to equality in their military service, both formally and on the ground, and that the army’s policy of barring them from service as pilots was unacceptable. This ruling had a profound effect on the units the IDF ordered opened to women, including those that until then had been an exclusively male monopoly. But the turning point created by the ruling was not just a matter of procedure. For all practical purposes, the court’s ruling ordered the IDF to integrate women into its ranks not only as a function of defense and security needs, but also based on the commitment to the principle of equality. This historic ruling sought to make clear to the state that the principle of equality was not being upheld as long as the phrase "defense requirements” was cited; the principle of equality must, for the most part, take precedence. As Justice Tova Strasberg-Cohen wrote: “In the conflict between the value of equality and the value of national security and military needs, national security may be regarded as of higher-priority, notwithstanding the importance of equality. But national security is not a magic word; it does not take precedence in every case and under all circumstances, nor is it of equal weight for all levels of security and for every security threat” (Miller vs. Minister of Defense).

From the Ruling on the Miller Case to the Present Day

On January 1, 2000, following the High Court of Justice’s ruling on Alice Miller’s petition, the Defense Service Law was amended to state that every woman, just as every man, had the right to serve in any position in the army unless the inherent nature of the position required otherwise. The first new position to be opened to women was that of air force pilot. This was followed, gradually, by fourteen other positions, such as naval officer, combat soldier in the Border Police (Mishmar Hagvul), anti-aircraft combat soldier, soldier in the Caracal combat unit, and combat soldiers in the Combat Rescue, Evacuation, and Airborne Medicine Unit.

Combat Positions Opened to Women, by Year

| Year | Position |

|---|---|

| 1995 | Pilots. |

| 1996 | Combat soldiers in the Border Police. |

| 1997 | Combat soldiers in anti-aircraft units; naval officers. |

| 2000 | Combat soldiers in the Caracal unit (the first mixed-gender combat unit); combat soldiers in the Combat Rescue, Evacuation, and Airborne Medicine Unit; combat soldiers in the Artillery Corps. |

| 2001 | Parachuting instructors. |

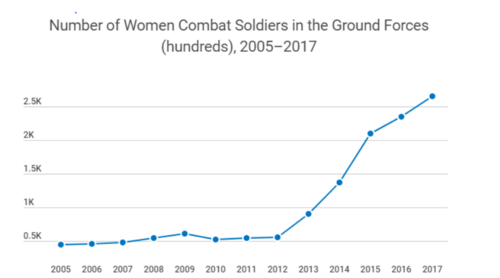

The first mixed-gender infantry unit, the Caracal Battalion, was established in 2004. Since then, the percentage of military roles open to women has increased steadily. In the 1980s, 55% of the positions in the IDF were open to women; in 1995 73%; and since 2012, around 86% of the IDF’s units have been open to women (Moshe). In addition, according to IDF statistics, the number of women combat soldiers in the infantry increased by 350% between 2013 and 2017, and the total number of women combat soldiers has increased sevenfold since 2005, as per the graph below (IDF Spokesperson’s Unit).

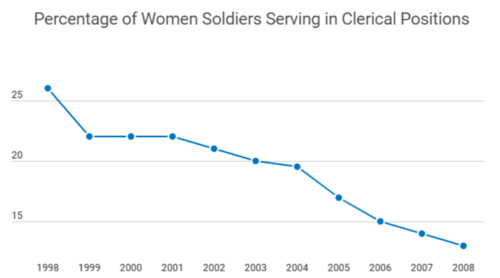

Concomitant with the increase in the percentage of women serving as combat soldiers, IDF officials report a decline in the percentage of women serving in clerical positions (IDF Spokesperson’s Unit).

Alongside the expansion of roles open to women, the IDF has taken measures to change its overall approach to women’s military service. As a reflection of this change, the Women’s Corps was dismantled in 2001 and the position of Advisor to the Chief of Staff on Women’s Affairs was established in its place (the title was later changed to the Advisor on Gender Affairs). The position was established to reflect the view that there should be no specific gender-based treatment of women’s affairs; rather, that women soldiers—just like their male counterparts—should be subordinate to their commanding officers in every way, except when it came to dealing with characteristics unique to women. The unit’s role includes promoting equal opportunities for women in the IDF. Army officials saw this act as a significant milestone in shaping the approach to women’s integration in the army.

In September 2007, the committee charged with defining women’s service in the IDF over the next decade, headed by Maj. Gen. (res.) Yehuda Segev, published its report. The committee established the principle of “the right person in the right place,” according to which “the abilities of men and women will be utilized to the fullest extent possible in service in an identical manner, according to objective criteria reflecting the army’s needs, and the energy, abilities, and personal traits of the conscripts, and not their gender.” The committee also stated: “No positions or units shall be categorically closed to women or to men” (Segev Report).

Following the committee's work, the IDF adopted a new strategic plan in 2010 to promote equal opportunities. This strategy was formulated after staff work conducted at the Yohalan unit (an adviser to the Chief of Staff on Women’s Affairs, later renamed the Adviser to the Chief of Staff on Gender Affairs) during 2009 indicated the need for a comprehensive systemic plan to address gender gaps, taking into account structural and cultural aspects. The goals of the plan formulated included, among other things, updating the Security Service Law in accordance with the IDF's vision, promoting gender awareness in the IDF, integrating the value of gender equality into the framework of "human dignity" in the IDF spirit, and empowering women.

Even though most of the Segev Committee’s recommendations were never adopted, since the ruling on the Alice Miller case commitment to gender equality has been a main motivation underlying the integration of women in the IDF. This holds true despite the fact that all agree that the decision to open more units to women also stemmed from the army’s need for highly motivated recruits. Evidence of this commitment may be found in the statement of Chief of Staff Gabi Ashkenazi in 2009, when he mandated that the IDF, as a people’s army, give high priority to striving for and implementing gender equality: "As the People's Army, which is a formative factor in the national ethos of the State of Israel, the IDF is committed, ethically, publicly and socially, to be the flag bearer in the field of women's integration [...] This is a moral obligation apart from the organizational need: Maintain the IDF as a strong, winning professional organization."

In his statement, Chief of Staff Ashkenazi listed three motives for integrating women on a footing equal to men into the IDF: 1) Women must serve in the army because the IDF is a people’s army; 2) As a people’s army, the IDF is committed to the principle to the integration of women; 3) Women are integrated into the IDF as part of operational requirements that are vital for keeping the army strong and professional. Despite the obvious trend toward opening up the army to women, however, today this equality is being challenged from new directions.

Defense Needs and the People’s Army: A Twist in the Plot?

In parallel to the opening of more and more units to women following the High Court of Justice’s ruling on Alice Miller’s petition, the percentage of national-religious men in the officers’ ranks of combat units has increased, as has the percentage of ultra-Orthodox conscripts (Magal). It became clear that conflict between the gender revolution in the IDF and the demands of religious male soldiers is unavoidable. For this reason, IDF officials ordered the development of regulations for joint service, with the intention being that these regulations would be anchored as standing orders. At first, in 2002, this order, known as the Proper Integration Ordinance, set rules for separate living quarters and modesty restrictions, while also stipulating the rights of the religious soldiers, such as refraining from certain activities requiring being with women in close quarters. With the increase over time in the number of women’s complaints that this order was being interpreted in an offensive manner and was leading to discrimination against and exclusion of women soldiers, the order was suspended. After many revisions, and while still arousing a public uproar of rare magnitude, the order was updated and its final version issued in December 2017 as the Joint Service Ordinance. Its opening statement reads, in part, as follows:

The purpose of the joint service policy is to meet the operational goal of the IDF and maintain unity in the military environment. It is based upon the fact that the IDF is the army of a Jewish and democratic state—and on the view of the IDF as a people’s army according to which soldiers of all types, religions, and ethnic groups serve in the IDF. The policy was established based on an official, egalitarian, and tolerant view, which is anchored in the values of human dignity and the spirit of the IDF”

The profound debate on the ordinance, which evolved into a fight between the religious Zionist community and women’s rights organizations, was conducted simultaneously along two tracks: a formal track with IDF officials, and a second track that took the form of a large-scale, bitter public campaign. The uproar about the ordinance and the way it was handled in the army raises many questions. Of particular interest is the fact that the campaign, led primarily by the national-religious sector, cited both factors—the model of the people’s army and defense needs, which had been the primary motivations for integrating women into the IDF when the state was established—as fundamental reasons to oppose the integration of women into various units. Time and again, the religious officials justified their opposition to the integration of women into operational units by stating that such integration, influenced as it was by radical feminist agendas, violated the principle of a people’s army and jeopardized the operational capabilities of the IDF and the defense of the state. The ordinance has been approved, however, and has been implemented in the various units in the IDF (Shafran-Gittelman).

Religious Women’s Service in the IDF

Another issue related to the issue of joint service in the IDF is the significant increase in recent years in the number of religious women who choose to serve in the army. According to the Security Service Law, religious women are exempt from service in the IDF. Indeed, most of them have traditionally applied for national service instead. In recent years, however, there has been a significant increase both in the number of religious women who choose military service and in the religious diversity of the schools from which religious women enlist. In June 2019, it was reported that the IDF estimates that within five years the number of the religious women serving in the various units in the IDF would double.

Although the issue of joint service is officially concerned with the welfare of male religious soldiers and the need to allow them respectful service in accordance with their The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic limitations, it seems that the fact that more and more religious women are violating the rabbinical directive not to enlist in the army is the core of the rabbis' opposition of the expansion of women's service in the IDF.

Even though the Joint Service Order does not address the question of women’s service in the IDF and the expansion of the units open to them, in both the public debate and the IDF’s discussions the question of joint service is linked with the fundamental issue of women’s service in various units, and mainly in combat ones.

Women's Service in Combat Units in the IDF

In September 2017 the IDF began a unique pilot program for training and integrating women as combatants in the Armored Corps. Although in June 2018 the Chief Armored Corps officer and Chief of Staff Gadi Izenkot crowned the pilot a success, the new Chief of Staff, Aviv Kochavi, decided not to place the women graduates of this endeavor as combatants in the corps and not to train more women for these positions. According to the IDF Spokesman, the decision was made due to manpower and infrastructure considerations, although no specific considerations were given. Opinions vary, however, as to the pilot program’s degree of success, and the pressure exerted by religious figures who oppose the integration of women in combat units raised suspicions that irrelevant considerations influenced the decision-making process.

In accordance with those suspicions, following the freeze on the pilot program, two women designated for service in the Armored Corps, as well as two female soldiers who completed the program, filed a petition to the Supreme Court, demanding the IDF integrate women into the Armored Corps as combatants, as planned and in light of the success of the pilot program. Another petition was submitted to the court by four women who demanded that they be allowed to be examined on "Patrol Day" for the special patrol units. To this was added the petition of H., who was expelled from a pilot course, demanding to be allowed to be examined for the same units that were offered to male soldiers who were expelled from the pilot course at the same stage as she was. Recently, another petition was submitted by a female soldier who was expelled from Seafarers course, demanding to be allowed to be examined for a special combat unit (DUVDEVAN).

As a backdrop to these petitions, on August 13, 2020, it was reported that Chief of Staff Aviv Kochavi had ordered the establishment of a team led by the commander the Ground Forces Command, Major General Yoel Strick, to examine the integration of women in combat units, including elite and infantry units.

As of 2021, according to data published by the IDF, in the last six years the number of women serving in combat infantry units has ballooned by 160%. The same report indicates that women now account for 18% of combat soldiers. However, the “assault echelon” has remained open to men only. As a result, despite the significant changes resulting from the expansion of women’s service in various units, gender remains a criterion for screening the assignments of military personnel. That seems to be the real question the IDF will have to face with regard to women's service: will it continue to assign its soldiers on the basis of gender, thereby erecting an insurmountable barrier to women’s admission to some units, or will it follow the trend in other democracies, opt for substantive equality, and assign its personnel only on the basis of professional standards?

Milestones in Women’s Service in the IDF

1949: The Defense Service Law, making army service compulsory for women, is passed. At the time this law was passed, the duration of military service was 30 months for men and eighteen months for women. According to the law, women could ask to be released from the army on grounds of religion or conscience.

1952: Amendments made to the Defense Service Law listed 25 positions open to women. The amendments also stated that women could volunteer for additional positions.

1987: The three permanent restrictions on women’s army service enumerated in the Defense Service Law, barring women from serving in combat roles, in positions in which conditions were not appropriate for women, and in positions that required physical strength, were abolished.

1995: Alice Miller’s petition was submitted to the High Court of Justice. The court ruled that women have the right to equal opportunity, both formally and in practice, in their military service, and that the army’s policy of barring women from serving as pilots was invalid.

1998: Sheri Rahat, a combat navigator, became the first woman to graduate from the pilots’ course.

2000: An amendment was adopted in the Defense Service Law stipulating that every woman has the right, equal to that of men, to serve in any position during her army service unless the inherent nature of the position demand otherwise.

2000: Ora Peled became the first woman graduate of the naval officers’ course.

2001: The Women’s Corps was dissolved.

2004: The first Caracal Battalion was established.

2007: The Segev Committee report was published. The report established, among other things, that placement should be based on the principle of “the right person in the right place” and stated that no positions or departments shall be closed categorically to either women or men.

2011: The first woman was promoted to the rank of Major-General: Orna Barbivai, head of the Manpower Directorate.

2014: Or Ben Yehuda was appointed the first woman company commander in an infantry officers’ course.

2016: The title “Chief of Staff’s Advisor on Women’s Affairs” was changed to “Chief of Staff’s Advisor on Gender Affairs.”

2017: The Joint Service Ordinance was updated.

2018: A woman was appointed commander of a flight squadron for the first time.

2020: Chief of Staff's decision to extend pilot program integrating women in armored corps was issued.

2020: A team led by the commander of the Ground Forces Command, Major General Yoel Strick, was established to examine the integration of women in combat units, including elite and infantry units.

2020: The Supreme Court decided to allow four women to submit a petition for the IDF to allow female conscripts to serve in elite combat units. The Justices also asserted that the IDF must complete the work of the existing committee that is examining the integration of women into combat units.

Almog, Shulamit, and Karin Carmit Yefet. “Religionization, Exclusion, and the Military: ‘Zero Motivation’ in Gender Relations?” Tel Aviv University Law Review 39, 2 (2016). [Hebrew]

Busidan, Ruthi. "Dreaming and Warriors: Did Women Really Fight for the Establishment of the State?" April 19, 2018; https://kibbutz.mynet.co.il/local_news/article/m_282565. [Hebrew]

Eran-Jona, Meytal and Carmit Padan. “Women’s Combat Service in the IDF: The Stalled Revolution.” Strategic Assessment 20 (4) 2018: 92.

HCJ 4541/94 Miller vs. Minister of Defense, 49(4) P.D. 94 (1995).

Lachover, Einat. “Women in the Six Days War through the eyes of the media.” Israel 13 (2008): 38.

Magal, Yaniv. Srugim Bakane: The Story of Religious Zionists’ Integration into the Army. Tel Aviv: Yedioth Ahronoth, 2016. [Hebrew]

Moshe, Neta. “Women’s Military Service in the IDF.” Submitted to the Knesset Committee for the Advancement of the Status of Women. Jerusalem: Knesset Research and Information Center, May 2013. [Hebrew]

Report of the Committee for the Design of Women's Service in the IDF in the Coming Decade, chaired by Major General (res) Yehuda Segev). September 2007.

Shafran Gittleman, Idit. “Women's service in the IDF and the Joint Service.” 143 Paper Policy, Israel Democracy Institute, Israel, June 2020. [Hebrew]

“A Special Survey: Women’s Service in the IDF.” IDF Spokesperson’s Office, July 2009.

Tevet-Wisel, Brig. Gen. Rachel, and Lt. Col. Ariel Weiner. “Forward in spite of everything.” Ma’archot 456 (August 2014): 39. [Hebrew]

State of Israel, Institute for Applied l Social Research (October 1949). Public Opinion on Drafting Women into the Army and Equalizing Women’s Rights, Publication 10. [Hebrew]

Tevet-Wiesel, Rachel and Lt. Col. Ariel Weiner. “Forward in spite of everything.” Ma’archot 456 (August 2014): 39. [Hebrew]