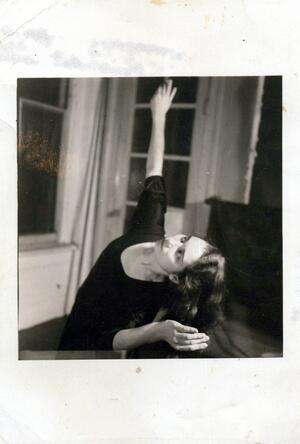

Ellida Geyra

Ellida Geyra was born in New York City. She briefly studied engineering before leaving the field to study dance at the Juilliard School under pioneering dancer/choreographer Martha Graham. While still in the United States, Geyra began dancing and choreographing, moving into film to photograph the dance group she founded. Her engineering background would become a great help in production of projects. Geyra immigrated to Israel in 1964, impacting the local dance and movement scene. She became the first woman in Israel to direct a feature film, in which she challenged the prevailing social representations. Her groundbreaking film Before Tomorrow was restored, screened, and placed back into the history of Israeli cinema as the starting point for woman’s cinema in Israel.

Childhood and Education

Ellida (Kaufman) Geyra, the first Israeli woman film director, was born on December 8, 1932, in New York City, into a religious, Zionist family. She was the only child of Binyamin Leib Kaufman, a physics and math teacher who was also a trained engineer, and Esther Kaufman, an elementary school teacher. After she graduated from high school, Ellida, encouraged by her father, began studying engineering.

After one year, Ellida left engineering to study dance at the Juilliard School under pioneering dancer/choreographer Martha Graham; she remained at the school from 1952 to 1956. While a student, she met Israeli painter and scenic designer Zvi (Tzitzi) Geyra, who worked in commercial television and Broadway theaters. They married in 1954 or 1955, and their first son, David, was born during Geyra's last year of studies.

Early Career: Dance as the Gateway to Film

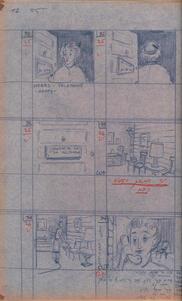

The World of Sholem Aleichem, with choreograph by Ellida Geyra, 1959.

After graduating from Juilliard, Geyra began her career as an independent dance teacher and choreographer. She choreographed for the 1959 television series The World of Sholom Aleichem, starring Zero Mostel; designed sets for Play of the Week; and established her own dance troupe. Geyra soon began to film the performances and realized (in her own words) “that onstage it is sometimes difficult to capture the little things, and make the emotions stand out” (Geyra, as quoted in Anderman). After one of the group’s performances, a Canadian producer approached her and proposed she join him in Canada and film the performance in his studio.

“I was intrigued,” Geyra remembered. “I traveled with him and he truly taught me what a camera is and how one directs. We photographed a short film I directed there. A short time afterwards Dance Film was screened on Canadian television and won an award” (quoted in Anderman). Geyra became enthusiastic at the infinite possibilities cinema offered: “A stage is a bit limiting, but in a film you can fly to the sky, jump around in time, and do whatever you want” (quoted in Anderman).

Immigration to Israel

An ardent Zionist, Geyra immigrated to Israel in 1964 with her husband and three children (David, b. 1956; Yoav, b. 1958; Amir, b.1960). She studied movement; worked as an extras coach at the Cameri Theatre and the Beit Zvi School for the Performing Arts; and worked with leading actors such as Haim Topol and Yehoram Gaon. She choreographed for plays and films, among them Nasser ad-Din and the film The Flying Matchmaker (1966, Two Kuni Lemels). She subsequently established a dance studio in her home, becoming acquainted with numerous actors who later participated in her films. At the same time, she also directed Prelude (1966), a 40-minute video-dance film set in nature and depicting a wordless love story between an older man and a younger woman, for the Israeli Film Service.

Geyra on Directing Before Tomorrow

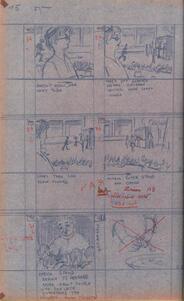

Before Tomorrow (1966), directed by Ellida Geyra.

In 1969, Ellida began directing her first full-length feature, Before Tomorrow. She later recalled,

Geva Films provided all of the services. Because the CEO’s daughter lived opposite me, we were friends of the entire family. I contacted them, and after a week or two they told me that there was financing. I am pretty OK in raising money, convincing someone that I know what I want. I was a “pusher,” I knew how to work [hard] and if I wanted to do something, I did it. Ezer Weizman and my husband were first cousins, and Tzitzi himself knew everyone. In Israel at the time, everything was run by “connections.” It was like a very small family.[…] I knew how to produce because I came from the field of engineering. I know how to get a project up and running. I had confidence (quoted in Shaer Meoded).

Before Tomorrow combines two short films: Spring (26 min.) and Fall (48 min.), each exploring love from a different viewpoint. Spring, an avant-garde film without dialogue, is an allegorical love story between two young people who dance their love, which awakens in open spaces. Fall is a drama, a love story between Mrs. Altmann, a German widow, and Mr. Ovadia, a Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi falafel seller.

In 1970, Ellida Geyra was nominated for the Kinor David Prize for Before Tomorrow; the lead actors were nominated for Actor and Actress of the Year.

The Importance of Ellida Geyra's Oeuvre

Before Tomorrow was screened at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1969 alongside Menahem Golan’s My Margo and Uri Zohar’s Fish, Football, and Girls [Our Neighborhood]. Israeli reviewers noted that it received far more applause than other Israeli films. Before Tomorrow was screened twice to full theaters and received favorable reviews from the foreign press.

Despite success at international festivals, however, the film was screened only a few times in Israel and was largely forgotten as time passed. This deliberate erasure of Geyra's film was part of a consistent framework of ignoring early films directed by women from the 1970s and 1980s. Film scholar Israela Shaer Meoded argues that films by women directors were excluded from the Israeli canon due to the films’ engagement with woman’s passion and sexuality, given that for decades the male narrative framed writing about Israeli cinema. An understanding of Israeli film as a male medium prevailed. In addition, the engagement with the issue of ethnicity in Israel made Before Tomorrow a groundbreaking film

In the film, even while Mrs. Altmann and Mr. Ovadia fall in love, the gaps between them in terms of social status and cultural spheres remain, and their relationship encounters a lack of empathy from their immediate environment. Altmann’s acquaintances stare at her wordlessly, as if scolding her for spending time with a “lower-class” man. Their gazes reflect the social climate in Israel during the decades when Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahim were marginalized as a group, politically, economically, and culturally; they were conceptualized as a “temporary problem to be addressed” (Motzafi-Haller 2001, 700) and their history was conceptualized as “redemption of the East by the West,” as noted by Israeli scholars such as Shohat, who focused on the image of the Mizrahim.

In contrast, the Zionist movement from its inception presented Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazim as western liberal democrats and Israel as a modern western society. Israeli cinema conserved these values of the Ashkenazi establishment without challenging them.

Geyra acted against this logic to create a realistic comedy-drama exploring the attempt to become more intimate, with all of its pitfalls and challenges. In the film’s final sequence, after an outing with Mr. Ovadia, Mrs. Altmann goes to her window and calls out to him as he walks away. Cinematic time is stopped in sequential shots: people stop what they are doing to observe her from below, neighbors go out to their balconies. Mrs. Altmann, whose borders have been breached, ignores them and charmingly asks Mr. Ovadia to come up for coffee.

In her film, Geyra delineates female passion as having been made possible by the political connection between two binary opposites in society and in Israeli cinema—Mizrahi and Ashkenazi. Thus, the first Israeli film directed by a woman marks the moment of desire as political, as Geyra creates a cinematic space for her protagonist to realize her desire and bring it to fruition.

Geyra's film was innovative in terms of genre, as well. Engaging with Israeli ethnic disparities was, in those years, almost exclusively the domain of commercial “bourekas movies” [from the word for phyllo-dough baked pastries], popular comedic films of the 1960s and 1970s with ethnic exaggerations. Geyra, by contrast, displaced it onto modern independent Israeli art cinema, which had already begun to disconnect itself from current social issues by the 1960s and 1970s. Geyra liberated both the “Yekke” [German] female protagonist and the Mizrahi male protagonist from their lack of representation in modern Israeli cinema and from their ridiculous representation in Israeli commercial cinema of those years. She strove to plant a new image of the man-woman connection in a field of distinctly readable fixed imagery

Even critical film theorists, film scholars, and reviewers who had written much about the representation of Mizrahim in “bourekas movies” (e.g., Shohat, Gertz, Yosef, Ben-Shaul) ignored this aspect of Geyra's film. Her viewpoint and the cinematic and cultural solution she proposed in her film for East-West relations were unusual and foreign to the logic of Israeli cinema. However, despite its local and international critical success, the film was largely forgotten in the history of Israeli film.

Later Career

During the 1970s, Geyra and her husband produced the series “An Evening with…” for Israeli Television, and Geyra directed documentaries commissioned by the Zionist Movement, Ministry of Information, Tel Hashomer Medical Center, and more.

In the early 1980s, after a personal crisis following a painful divorce, Geyra gradually left the field of cinema and returned to teaching dance and initiating projects such as founding the dance department for Omanut La’am, a government institution bringing culture to the geographic and social periphery. She also served as artistic director of the Gvanim dance group and manager of Matan, an organization identifying disadvantaged youth talented in the arts and helping them advance. She was among the founders of the Gvanim Shades in Dance Festival and of the Israeli Dance Library.

Belated Recognition of Before Tomorrow

The doctoral dissertation by Israela Shaer Meoded, The Unknown Cinema: On Early Women's Cinema in Israel (1969-1983), rediscovered Geyra's film and conceptualized and named it as the point when women’s cinema began in Israel.

In 2013, Shaer-Meoded initiated the film’s restoration (financed by the Geyra family), as well as screenings at the International Women’s Film Festival in Israel and at most of the country’s cinematheques. The screening was covered by Israeli television and the local press, granting Ellida Geyra belated and long-overdue recognition by the establishment.

Ellida Geyra passed away on May 10, 2017.

Anderman, Nirit. “Where did the first woman director of Israeli cinema disappear to?” Haaretz, Octover 21, 2013. [Hebrew]

Motzafi-Haller, Pnina. “Scholarship, Identity, and Power: Mizrahi Women in Israel.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 26.3 (2001) 697-734.

Shaer-Meoded, Israela. “The Unknown Cinema: On early women’s cinema in Israel, 1969-1983.” Unpublished Master’s Degree Thesis, Tel Aviv University, 2016.

Shenhav, Yehuda. The Jewish-Arabs: National feeling, religion, and ethnicity. Tel Aviv:Am Oved, 2004. [Hebrew]

Shohat, Ella. Israeli Cinema: History and Ideology. Tel Aviv: Breirot, 1991. [Hebrew]

Yosef, Raz. “Ethnicity, trauma, and ethical responsibility: Mizrahi women in the new Israeli cinema.” Mikan, 13 (2013): 106-123. [Hebrew]