Zohra El Fassia

Zohra El Fassia was a renowned singer and recording artist in mid-twentieth-century Morocco. Born to a Jewish family, El Fassia lived and worked in Morocco in the first half of the century and immigrated to Israel in the early 1960s. A definitive narrative of El Fassia remains elusive. But conversations with descendants, fellow artists, and colleagues, together with research on North African Jewish history, begin to construct the story of a woman unflinchingly guided by strong artistic conviction and a hunger for life, song, and stage. This story moves between the international recording industry in Morocco and the immigrant North African cultural world of the Israeli periphery and traces the turbulent contours of Moroccan Jewish life through twentieth-century colonialism and emigration.

Zohra El Fassia was a renowned singer and recording artist in mid-twentieth-century Morocco. Born to a Jewish family, El Fassia lived and worked in Morocco in the first half of the century and immigrated to Israel in the early 1960s, where she spent the final three decades of her life. A definitive narrative of El Fassia remains elusive. But conversations with descendants, fellow artists, and colleagues, together with research on North African Jewish history, begin to construct the story of a woman unflinchingly guided by strong artistic conviction and a hunger for life, song, and stage. This story moves between the international recording industry in Morocco and the immigrant North African cultural world of the Israeli periphery and traces the turbulent contours of Moroccan Jewish life through twentieth-century colonialism and emigration.

The Woman from Fez

Zohra El Fassia was born in 1905 (1912 according to some accounts) to Naomi and Eliyahu Hamou in the city Sefrou. It was the nearby city Fez, however, that would grant her the regional title “El Fassia” (the woman from Fez), by which she came to be widely known. El Fassia had one older sister, Simcha, though the two would maintain a longstanding and lively debate about which of the sisters was firstborn. Their father, Eliyahu, was a butcher who also sang as Synagogue cantorhazzan in the neighborhood synagogue. This is possibly where El Fassia first exercised her own singing voice, learning Hebrew liturgical poempiyyutim and by extension the North African repertoires on which their melodies were based. The young El Fassia likely attended primary school through the Alliance Israélite Universelle, the French Jewish educational system that by the start of the twentieth century had spread throughout the Maghreb with an express aim to Europeanize its Jewish residents. In her older age, El Fassia recalled that as a schoolgirl she sought to sing at every possible opportunity, so much so that her schoolteacher predicted that she would no doubt grow up to become an artist.

Both El Fassia and her sister were wed at very young ages, taken out of school either by family or by Alliance policy that banned married girls from attending. El Fassia married a man from Fez named Avraham Saadon and gave birth to her first daughter, Marcelle, likely around the age of thirteen. In the following years, she had two more children, son Sam and daughter Annette. At the same time, she was also making strides as a performer. Later in life, she recalled going out to hear and sing with touring musicians traveling through the city, then excitedly reporting on the adventures to her mother. Following the musicians’ encouragement, the young El Fassia increasingly performed at weddings and other private parties and events. At the age of eighteen, she divorced her husband and moved, either immediately or some years later, to Casablanca, the largest city in Morocco. The children stayed with their father in Fez, growing up alongside four half-siblings, their father’s children with his second wife. In Casablanca meanwhile, El Fassia began a new relationship with Mr. Tappiero, a married man who had left his wife to be with the up-and-coming singer. The pair had three daughters together, Monette (née Henriette), Solange, and Suzane, who died as a baby.

Maalema Zohra El Fassia

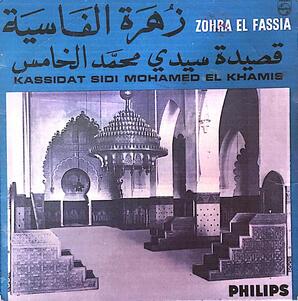

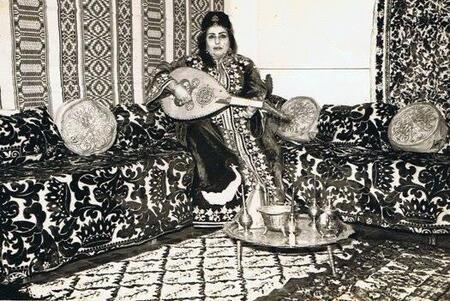

El Fassia became a star. Garnering the honorific cheikha or maalema (master), she emerged as a central figure in the recording industry that burgeoned in the colonial Maghreb in the first half of the twentieth century. She became particularly respected as a singer of malhun, or qasidas, long-form colloquial poems set to music, narrating stories of politics and history, beauty and heartbreak. Some songs were written by poets especially for her, some she wrote herself. Beginning in the 1930s, El Fassia released dozens of 78 rpm records with prominent international labels such as Pathé, Philips, and Polyphon. Among the first generations of singers to record in North Africa, she was at one point deemed “the most renowned of Moroccan female vocalists” (Mahieddine Bachetarzi, artistic director for Gramophone, quoted in Silver 2017, 61 n. 158). In this, she was part of a cohort of high-profile Jewish musicians across North Africa who attained widespread mainstream success. This was, ironically, at a time when the social fabric of Jewish life in Morocco was beginning to break apart in response to a host of social and political transformations that included Zionism and the displacement of Palestinians in the formation of the Israeli state in 1948, as well as growing anti-colonial Arab nationalism and Moroccan independence from the French and Spanish protectorates beginning in 1956.

Famously, El Fassia sang frequently at the royal palace of Sidi Mohammed ben Yusef, first Sultan, then King Mohammed V of Morocco, whom she adored. As historian Chris Silver notes, her rendition circa 1954-55 of the song “Hbibi Diali” (“My Love”), was almost certainly recorded within the widespread longing for the return of the then-exiled Sultan to his country. El Fassia also likely composed her own qasidas for the King, as well as for his son, future King Hassan II. This participation of Jews, key among them many Jewish musicians, in the celebration of Moroccan patriotism challenges more dominant narratives that exclude Jews from the anti-colonial moment. And the celebration of the royal family, part of the centuries-old Alaouite dynasty, would continue to permeate not only El Fassia’s individual story but also the collective story of Moroccan Jewish life both past and present. The renowned musical Botbol family recalled hosting El Fassia in performances with their own ensemble, which played regularly in the palace in Rabat. In addition to singing at the enthronement, El Fassia recalled singing in performances planned by the King in various cities and villages to ease the social tensions that periodically arose between Jews and Muslims.

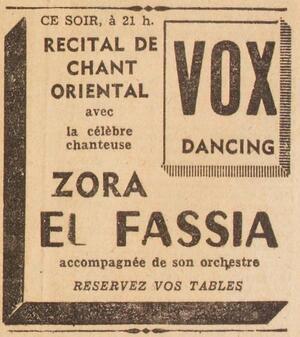

Beyond the recording studio and the palace, the traces of El Fassia’s story reveal a busy, in-demand working musician who navigated an industry predominated by men and booked gigs across contexts. In Casablanca, she sang at various mainstream clubs and music venues, including the prestigious Cinema Vox and the smaller Le Bristol, and appeared on radio stations like Radio Maroc. She performed alongside working musicians, such as oud player David Ben Harosh, as well as fellow headliners, including Louisa Tounsia and Salim Halali. In addition to recording her, the international labels also arranged shows and travel dates along the axis between France and North Africa. She recalled, for example, that the Philips label took her on tour throughout Algeria, and she may have at one point traveled to Marseille to record for one of the labels. No doubt, however, her bread-and-butter performances took place in sought-after private events and family celebrations across the country, both Jewish and Muslim. In these, El Fassia’s bottomless energy for both the stage and her audience, combined with her fluency in the long form of the malhun, provided for hours and hours of music.

Emigration: From Casablanca to Ashkelon

Sometime between 1962 and 1964, with a track record of a prolific and illustrious performance and recording career that spanned genres, crossed borders, and rubbed shoulders with the Alaouite dynasty, Zohra El Fassia left Morocco. In this, she was one of over 200,000 Jews who left Morocco between 1948 and 1967 and relocated in phases to Israel, France, and North America in response to the seismic geopolitical changes that gripped North Africa and the Middle East at the time. El Fassia immigrated to Israel, joining her sister Simcha who had been living in Jerusalem with her husband Avraham Hayon since 1917. She had in fact visited once, but not stayed, some years prior, a visit that Simcha’s youngest daughter Batsheva remembers as one marked by fur coats and French perfumes set against the dull background of Israel’s austerity period. In the 1960s, El Fassia, together with her third partner Moise, or Moshe, Cohen, settled in the southern coastal town of Ashkelon. The couple lived in a state-owned apartment in a neighborhood known as ‘Atiqot Gimel (translated by Ammiel Alcalay as “Antiquities 3”) in the southern end of the city, where Cohen also owned and operated a kiosk down the block from their apartment. The southern periphery became the site of settlement for many North African immigrants, across transit camps, public housing blocks, or rapidly built development towns. El Fassia’s children dispersed across the various nodes of the Moroccan Jewish diaspora. Three of her daughters—Marcelle, Monette, and Solange—immigrated to France and the United States, her son Sam lived near her in Ashkelon, and her daughter Annette, settled nearby in the southern city of Beersheba.

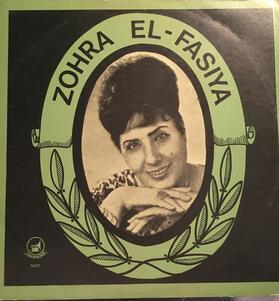

In an Israel that grouped and disenfranchised Jews from the Arab and Muslim world under the collectivity of Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahim, and rejected and siphoned off Arab music and culture, El Fassia regained neither the opportunities to work nor the recognition the that she had in Morocco. This was the reality of many immigrants, and in particular of Arabic-speaking musicians, including, for example, the immensely influential Iraqi brothers Saleh and Daoud Al-Kuwaity. A 1965 article, likely the first mention of El Fassia in Israeli media, reported on her in relation to a museum exhibit on North Africa to which she lent some of her fine clothing and in which she herself appeared as a curated part of the exhibit. Her nephew Uri Hayon recalled that so great was her desire to perform and to share her knowledge and voice that she would approach news and radio stations with offers of some of her finest artifacts in an attempt to secure gigs. Within the Moroccan immigrant community, El Fassia was periodically invited to perform, for example, in the large-scale productions of the Mimouna (a Moroccan celebration at the end of A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover) that entered the national stage in Sacher Park in Jerusalem in 1965 under the leadership of cultural activist and fellow Fassian Shaul Ben Simhon. El Fassia recorded a number of songs with Zakiphone (later Koliphone), the Jaffa-based independent record label founded in 1953 by the Moroccan-born Azoulay Brothers, which recorded, almost singlehandedly, wide swaths of Mizrahi music in the first decades of the state. Her Zakiphone recordings of well-known songs, such as “Abyadi Ana” and “Moulay Brahim,” enjoyed wide circulation and airplay within the immigrant Moroccan community. But even within the community, she seemed to remain caught between two worlds, neither as legible as her younger counterparts who sang lighter and catchier songs than her more elaborate malhun, nor a part of the largely male and more religiously affiliated piyyutim musical community.

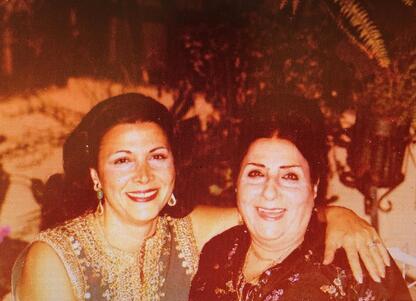

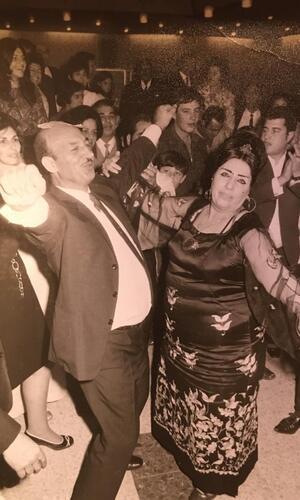

El Fassia’s artistic spirit, however, never waned. She sang everywhere and anywhere and in her older age insisted on continuing to sing even around the younger musicians, never tiring of the stage. In video recordings of the musician-studded 1989 bar mitzvah of the son of Moroccan-born musician Cheikh Mwijo, she is seen singing while seated on the stage alongside younger musicians, including Nino Bitton and David Nidam, guarding the microphone from other encroaching singers and showered with bills and kisses by doting party members. In a 1991 event in her honor in Ashkelon, scholar of North African song Joseph Chetrit recalls that, despite her frailty in old age, she insisted on singing a particularly long and complex qasida. El Fassia missed no opportunity to get entirely dressed and made up, including painting on her signature three black beauty marks. Her daughter Monette was one of her ultimate admirers and from Los Angeles brought her the tiaras she wore on a regular basis. With the Jerusalem branch of the family, her nephew Uri Hayon organized big gatherings in which El Fassia could enjoy a glass of Chivas Regal, her favorite whiskey, and was given a platform to perform, which she would do for hours, improvising songs packed with political commentary, innuendo, and humor. Her great-niece Tallia Amos remembers the rounds of claps that she would request from her audience in order to bring about a steady vibration before she started to sing, and granddaughter Laurence recalls a song El Fassia devised about herself that she would sing especially in order to announce the beginning of festivities.

Afterlife: Social and Cultural Resonance

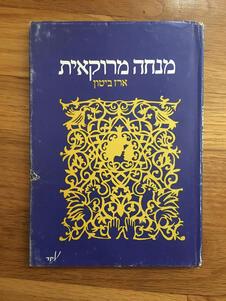

Though El Fassia did not find an outlet for her music in Israel, her story began to circulate, leaving its mark on younger generations of Moroccan and Mizrahi Jewish artists. For them, El Fassia’s music, story, and persona provided a portal to the cultural richness of Jewish diasporic life, as well as a way to narrate the story of loss in the migration to Israel. Algerian-born poet Erez Bitton wrote “Zohra El Fassia’s Song,” published first in the daily Maariv (1975) and then in his first anthology Minḥah Maroḳaʾit (Moroccan Mincha, 1976). Based on a chance visit to her while he worked as a social worker in Ashkelon, and processed through Bitton’s sharp lens of social critique, the poem traces the stark difference between El Fassia’s grandeur in Morocco and her immigrant experience in Antiquities 3.

Other independent Mizrahi artists followed in Bitton’s footsteps, restaging the encounter with El Fassia piecemeal. Musician Shlomo Bar cites his visit to El Fassia in the late 1970s as pivotal to the path of his formative band Habrera Hativ’it (Natural Gathering). The independent Mizrahi theater company Bimat Kedem staged a monologue by El Fassia’s character in its debut play, the 1983 one-woman show entitled Nashim Shel Mamash (Real Women), performed and directed by Iraqi-born actress Shosha Goren. Later in the 1980s, Moroccan-born filmmaker Haim Shiran (who recalls meeting El Fassia through his wife, Mizrahi feminist activist and political figure Vicki Shiran) began in his off-hours to meticulously document her life and career. In addition to filming her, Shiran tirelessly advocated for El Fassia’s recognition in her final years, and her music permeates his own work, including her recording of the song “Abyadi Ana” in a wedding scene in his film Tehila leDavid (Glory to David). Years later, in 2016, artists Neta Elkayam and Amit Hai Cohen, both children of Moroccan Jews, born and raised in in the Israeli south, produced Abiadi, a multimedia tribute performance to El Fassia. Throughout these renderings, El Fassia’s story and music linger in a rich cultural reality, away from the eyes of the Israeli mainstream.

Zohra El Fassia passed away on November 4, 1994. She was survived by a large extended family that included several musicians and visual and performing artists in their own right across Israel, France, and the United States. Family members recall that El Fassia’s funeral and Lit. "seven." The seven-day mourning period held following the death of an immediate family member: spouse, parent, child or sibling.shivah were attended by notable Mizrahi musicians and artists, as well as an official representative on behalf of King Hassan II. In Ashkelon, they paid their respects to the woman from Fez.

Selected Recordings by Zohra El Fassia:

Aita Moulay Brahim (Chant Chleuh). Vinyl. Pathé, 1950s.

Ayli Ayli Hbibi Diali. Vinyl. Philips, c. 1954-55.

Lâarosa. Vinyl. Zakiphon, 1960s.

Mayli Sadr Hnine. Vinyl. Pathé, c. 1956.

Zohra El Fassiya Laarosa-Chansons Marocaine Oriental. CD. Jaffa: Zakiphon, n.d.

Zohra El Fassiya: La’arousa. DVD. Koliphone-Zakiphone Azoulay, n.d.

Zohra Elfassia - Haklatot ve-Ha-Bitsu’im Ha-Mekoriim - CD 1 [Original Recordings and Songs]. CD. Jaffa: Zakiphon, n.d.

Zohra Elfassia - Haklatot ve-Ha-Bitsu’im Ha-Mekoriim - CD 2 [Original Recordings and Songs]. CD. Jaffa: Zakiphon, n.d.

Art works that feature or center Zohra El Fassia:

Bimat Kedem. Nashim Shel Mamash.[ Real Women]. Play, 1983.

Bimat Kedem. Zohra El Fassia The Musical. 2013.

Bitton, Erez. “Shir Zohra El Fassia.” Minḥah Maroḳaʾit [Moroccan Mincha]. Tel Aviv: ʻEḳed, 1976.

Bitton, Erez. “Zohra Al-Fasiya’s Song.” In Keys to the Garden: New Israeli Writing, translated by Ammiel Alcalay, 267–68. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1996.

Elkayam, Neta. Abiadi: A Tribute to the Legendary Zohra Al Fassia. Multimedia performance, 2016.

Revach, Ze’ev. Kehilat Kdoshim [A Community of Saints]. DVD, 2008.

Shiran, Haim, and Israeli Educational Television. Tehilah le-Daṿid [Glory to David]. Tel Aviv: Israeli Educational Television, 1989.

Steinhardt, Alfred. Mah ḳarah le-Yahadut Maroḳo [What happened to Moroccan Jewry]. Jerusalem: Israeli Film Service, 1975.

T’Kuma - Israel Hashniya [Rebirth: Second Israel]. Israel Broadcasting Authority (IBA), 1998.

Alcalay, Ammiel. After Jews And Arabs: Remaking Levantine Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Amos, Tallia. Phone interviews with the author, July 15, 2020; July 18, 2020; February 28, 2021.

Barzelai, Laurence. Phone interview with the author, July 28, 2020.

Boum, Aomar Memories of Absence: How Muslims Remember Jews in Morocco. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2013.

Chetrit, Joseph. Interview with the author, October 9, 2018. Haifa.

Chetrit, Joseph. Phone interview with the author, July 28, 2020.

Chetrit, Sami Shalom. Intra-Jewish Conflict in Israel: White Jews, Black Jews. London; New York: Routledge, 2010.

Dor, Batsheva. Phone interview with the author, August 3, 2020.

Elkayam, Neta. Phone interview with the author, July 29, 2020.

Elkayam, Neta, and Amit Hai Cohen. Interview with the author, August 20, 2018. Jerusalem.

Glasser, Jonathan. The Lost Paradise: Andalusi Music in Urban North Africa. Vol. 153. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Goren, Shosha. Interview with the author, March 19, 2019. Tel Aviv.

Gottreich, Emily. Jewish Morocco: A History from Pre-Islamic to Postcolonial Times. London: IBTauris, 2020.

Herman, Batsheva. “Unusual North African Exhibit Opens Today in Jerusalem.” The Jerusalem Post, January 13, 1965. From Haim Shiran’s Archive.

Ronen, Offer, Elia Meron, and Edwin Seroussi. “Song of the Month: November 2015: Abyadi Ana.” Jewish Music Research Centre, November 2015. https://www.jewish-music.huji.ac.il/content/abyadi-ana.

Seroussi, Edwin. “Music.” In Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, edited by Norman A Stillman, 498–519. Leiden, Koninklijke Brill NV, 2010.

Shalev, Ben. “Ha-Sipur Ha-Amiti Meahorei Agadat Zohra El Fassia [The True Story behind the Legend of Zohra El Fassia].” Haaretz, November 17, 2016. https://www.haaretz.co.il/gallery/music/.premium-MAGAZINE-1.3123054.

Shemoelof, Mati. “Bar ba-Shetah: Reayon Im Shlomo Bar [Bar in the Field: An Interview with Shlomo Bar].” https://matityaho.com/, July 19, 2006. https://matityaho.com/2006/07/19/%D7%91%D7%A8-%D7%91%D7%A9%D7%98%D7%97/.

Shiran, Haim. Interviews with the author, June 18, 2018; November 29, 2019. Tel Aviv.

Shohat, Ella. “Sephardim in Israel: Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Jewish Victims.” Social Text, no. 19/20 (1988): 1–35.

Silver, Christopher. “The Sounds of Nationalism: Music, Moroccanism, and the Making of Samy Elmaghribi.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 52, no. 1 (2020): 23–47.

Silver, Christopher Benno. “Jews, Music-Making, and the Twentieth Century Maghrib.” Ph.D., University of California, Los Angeles, 2017.

Silver, Christopher. “Listening to the Past: Music as a Source for the Study of North African Jews.” Hespéris-Tamuda LI (2) (2016): 243-255.

http://search.proquest.com/docview/1944388685/abstract/30BB5C027A26493FPQ/1.

Silver, Chris, Personal e-mail communication with the author, August 8, 2020.

Silver, Chris. “Sonic Geniza: Finding Zohra El Fassia in Los Angeles.” Sephardic Los Angeles, 2020. http://www.sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/sonic-geniza/.

Silver, Chris “Zohra El Fassia – Ayli Ayli Hbibi Diali [Sides 1-2], Philips, c. End of 1954-1955.” .Gharamophone (blog), February 24, 2020. https://gharamophone.com/2020/02/24/zohra-el-fassia-ayli-ayli-habibi-diyali-sides-1-2-philips-c-end-of-1954-1955/.

Silver, Chris. “Zohra El Fassia – Mayli Sadr Hnine – Pathé, c. 1956.” Gharamophone (blog), June 25, 2018. https://gharamophone.com/2018/06/25/zohra-el-fassia-mayli-sadr-hnine-pathe-c-1956/.

Silver, Chris. “Reinette l’Oranaise – Ya Biadi Ya Nas – Polyphon, c. 1934.” Gharamophone (blog), December 14, 2017. https://gharamophone.com/2017/12/14/reinette-loranaise-ya-biadi-ya-nas-polyphon-c-1934/.

Silver, Chris. “The Azoulays, Jewish Libyan Cassettes and Zohra El Fassia’s Great Granddaughter.” Jewish Maghrib Jukebox (blog), March 11, 2012. https://jewishmorocco.blogspot.com/2012/03/azoulays-jewish-libyan-cassettes-and.html.

Silver, Chris . “Ya Nas, Ya Nas – Zohra El Fassia Digitized.” Jewish Maghrib Jukebox (blog), June 22, 2011. https://jewishmorocco.blogspot.com/2011/06/ya-nas-ya-nas-zohra-el-fassia-digitized.html.

Silver, Chris. “Cheikha Zohra El Fassia.” Jewish Maghrib Jukebox (blog), August 4, 2009. https://jewishmorocco.blogspot.com/2009/08/cheikha-zohra-el-fassia.html.