Bianca Eshel-Gershuni

Born in Bulgaria in 1932, Bianca Eshel-Gershuni was a pioneering sculptor and jeweler whose work significantly influenced generations of Israeli artists. She exhibited in major national institutions in public and private collections. From the late 1960s to the late 1970s, she revolutionized traditional jewelry design, boldly merging “high” and “low” aesthetics in a way that was seen as almost sacrilegious. In the 1980s and 1990s, she expanded into large-scale sculpture and installation, challenging the boundaries between craft and fine art. Her richly material, expressive, and narrative works stood in stark contrast to the dominant minimalist and conceptual trends of the time, paving the way for future engagement with kitsch, gender, ready-mades, popular culture, and biography.

Early Life and Family

Bianca Eshel-Gershuni was born Bianca Moskona, daughter of Leon Moskona, a wealthy wool merchant and textile engineer, and Esther Moskona, on November 25, 1932, in Sofia, Bulgaria. Her older brother Jackie was ten years her senior. When Bianca was a child, her father took her to Bulgarian Orthodox churches, where the stained-glass windows and images of the crucifixion made a deep and lasting impression on her and influenced her artistic vision. His early death in 1959 left a lasting impact.

In 1939, after being warned that he was on a German blacklist and likely to fall victim to anti-Jewish laws, given Bulgaria’s increasing dependence on Germany, Leon Moskona moved his family to Mandatory Palestine. Bianca was seven at the time. Building on his professional connections, he established the Elmo wool-weaving factory and the family settled in a prominent Bauhaus home in Tel Aviv. As a child, Bianca was considered rebellious and often clashed with her loving but dominant father. Raised in a cultured home, surrounded by art books, she developed the early aspiration to become an artist. Years later, she described art as the means by which she saved herself from loneliness.

In the early 1950s, during her military service in the Israel Defense Forces, Eshel-Gershuni met her first husband, Eliyahu Eshel, a pilot in the Israeli Air Force. They had one daughter, Atar. In 1956, Eliyahu was killed in the Sinai Campaign, leaving Bianca a young widowed mother. She supported herself while continuing to pursue her artistic path.

In the 1960s, Eshel-Gershuni began studying sculpture and painting at the Avni Institute of Art and Design in Tel Aviv, attending afternoon classes while her mother cared for her daughter. Established in 1936, the Avni Institute is Tel Aviv’s oldest art school, attended by many prominent Israeli artists and designers. During her studies, she met the artist Moshe Gershuni, whom she married in 1964. The couple had two sons: the painter Aram Gershuni and the photographer Uri Gershuni. They settled in Ra’anana, on Israel’s Sharon Plain. During the 1970s and 1980s, their home became the hub of a vibrant community of artists, including Raffi Lavie and other leading figures in the Israeli art world.

Revolutionary Jewelry/Miniature Sculpture

From the early 1960s to the late 1970s, Eshel-Gershuni worked as a jeweler with no formal training. She began her career at the Kafilo-Yaglom art and jewelry company in Jaffa, creating pieces using traditional techniques like hammering and soldering, often drawing on local stylistic elements. By the end of the decade, she had developed a distinct artistic voice, working in gold and integrating various ready-made materials.

In the years that followed, Eshel-Gershuni emerged as a pioneering figure in Israeli jewelry design, introducing radical innovations that challenged traditional norms. Her pieces were monumental in scale—an unusual characteristic in the context of jewelry—and crafted from 24-karat gold, onto which she added cheap market-sourced materials, such as feathers, candy wrappers, plastic flowers, small toys, fur, and mirrors. These combinations deliberately juxtaposed the “high” with the “low,” deconstructing conventional hierarchies and rethinking the relationship between jewelry and the human body. Although at times worn by herself or others, the unique scale and character of her creations located them firmly within an artistic context, and they were acquired primarily by collectors and museums.

In 1977, Eshel-Gershuni held her first major solo exhibition, titled Bianca Eshel-Gershuni: Jewelry, at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The show featured a diverse range of objects—part miniature sculpture, part jewelry—that marked her most significant blurring of boundaries between craft and fine art. Curated by Yona Fischer, the museum’s curator of contemporary art, the exhibition was presented in the art wing rather than the design department, signaling institutional recognition of her work’s artistic significance. Fischer noted that Eshel-Gershuni’s use of unconventional materials embodied this shift: “The encounter between the delicate material and the banal object symbolizes a sharp and dramatic interaction between the distant, elevated realm of art and the accessible world of everyday things” (Fischer 1977, 30).

Eshel-Gershuni’s contributions are particularly significant given the marginal status of contemporary jewelry in Israel at the time. While radical jewelry movements gained momentum in Europe and the United States during the 1970s and 1980s, similar developments were slow to emerge locally. It was not until 1998 that Israel hosted its first jewelry biennial—an initiative co-founded by Eshel-Gershuni and jeweler Esther Knobel.

Despite the prestige of exhibiting at the Israel Museum, the Israeli art establishment did not fully embrace Eshel-Gershuni’s jewelry as a meaningful intervention in sculptural discourse. Her works were monumental as jewelry, yet small-scale by the standards of contemporary sculpture. At a time when Israeli sculpture was dominated by minimalist, abstract, and conceptual trends—typically large works executed in materials like iron, wood, and stone—her expressive and intimate pieces were out of place.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Eshel-Gershuni continued to exhibit her art in Israel and abroad. In 1990, she held a major exhibition at the Sara Levi Gallery in Tel Aviv, known for its high curatorial standards. The show featured a series of round brooches, approximately 10 centimeters in diameter. As in her earlier works, they combined miniature narratives with a striking mix of materials, pairing precious elements like pearls and pure gold with everyday items such as plastic toys, hearts, and seashells. Some brooches referenced graves and crucifixions, while others drew on mythological imagery, including eyes, spirals, centaurs, and mummified figures. Art historian Dalia Manor described them as acts of rebellion against artistic and social norms, achieved through the deliberate clash of opposites: luxury and banality, joy and death, beauty and anxiety, ornament and art—what she called “the fear of life and the beauty of death” (Manor 1990, 42).

Revolutionary Sculpture: Ready-Mades and Monumental Forms

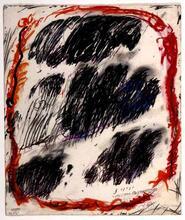

The 1980s and 1990s also marked a significant shift in Eshel-Gershuni’s practice, as she moved from small-scale jewelry to large sculptures and installations. Continuing to use ready-made objects, she developed a distinctive visual language that introduced a different aesthetic and thematic model into Israeli art. Her works often featured motifs from Eastern Orthodox and Christian iconography, and they were distinguished by rich textures, vivid colors, sensuality, and narrative complexity.

In 1983, Eshel-Gershuni presented her first large-scale sculptures alongside her earlier pieces of jewelry from the Israel Museum in a solo exhibition at Dvir Gallery in Tel Aviv. A notable piece, Celebration in Paradise, a visually arresting and symbolically charged assemblage, features a baroque, theatrical shrine-like scene of cheap plastic pastoral figurines, their bodies smeared with red like blood and set amid fur and feathers—poised in a deliberately ambiguous state between life and death.

Eshel-Gershuni’s first major solo exhibition, Bianca Eshel-Gershuni: 1980–1985, was held at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1985, curated by Sarah Breitberg-Semel, then the museum’s curator of contemporary art. This exhibition juxtaposed her jewelry with expressive sculptural works that featured recurrent themes of graves, tombstones, crucifixion, and resurrection. It concluded with two striking, large-scale canvases: I Asked Only that You Should Be, featuring a crucified male figure with an erect phallus, and Primavera, portraying a pale female figure surrounded by plastic and fabric flowers and colorful ornaments, which filled the surrounding space. In Primavera, the woman’s pale figure is accentuated by the intense coloration and material richness, her genitalia symbolically rendered as a cluster of grapes, while an infant figure appears almost submerged in the surrounding excess.

This exhibition coincided with a major turning point in Eshel-Gershuni’s personal life when her husband, Moshe Gershuni, came out as gay and left her. A leading figure in Israeli modern art and recipient of the Israel Prize, Gershuni’s separation from his wife marked the dissolution of a once-central artistic household linked to Raffi Lavie’s circle.

The exhibition framed Eshel-Gershuni’s sculptures as responses to this rupture and to broader crises surrounding traditional notions of femininity. As a result, her work was frequently interpreted through biographical and psychological lenses, often reinforcing gender-essentialist narratives that linked her art to themes of abandonment and loss. While sympathetic, these readings risked reducing her practice to stereotypical expressions of “femininity.” In recent years, such interpretations have been subject to more critical approaches that emphasize instead the feminist, political, and national aspects of Eshel-Gershuni's work (Carmi 2022).

In the 1990s, Eshel-Gershuni started using the turtle as a central symbolic motif, while continuing to employ her signature aesthetics and assemblage technique. She produced turtle sculptures on various scales, often featuring cruciform poses and embellished with different textures. The turtle emerged as a symbol of domestic burden, personal reflection, and mature femininity in her art, and it was frequently interpreted as a form of self-portraiture. Works from this series were exhibited in two solo shows at the Sara Levi Gallery (Well in a Tortoise Shell, 1993, and The Sisyphic Tortoise, 1995) and later in Step by Step (2001) at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, curated by Sorin Heller.

Until her death on April 23, 2020, Eshel-Gershuni continued to produce both large-scale sculptures and miniatures, dioramas, and jewelry, which she exhibited in solo shows in major Israeli museums and galleries. In her later years, she turned to digital painting, creating vividly colorful compositions using basic software and further expanding her distinctive visual language.

Reception

Through her style, content, and artistic approach, Eshel-Gershuni anticipated developments that emerged in the international art world long before they took hold in Israel: concern with gender, the re-appropriation of handicraft, openness to art with biographical dimensions, a return to narrative, materiality, emotion, and the crossing of boundaries of post-modern trends.

Despite the bold, multifaceted nature of her work, Eshel-Gershuni remained an outsider vis-à-vis the Israeli art world for many years. While she was recognized in the field of jewelry design, her broader practice was largely excluded from the dominant artistic discourse. In the modernist-Israeli framework of the 1970s and 1980s, personal expression was deemed extraneous to legitimate artistic practice. Influential critics and curators upheld a narrative that persisted into the early 2000s, framing Israeli art as unified by emotional restraint, intellectual aloofness, and a critical distance from materiality.

In contrast to the prevailing dominant minimalist and conceptual trends, the richness, abundance and sensuality of Eshel-Gershuni's art, with its biographical, feminist perspective, provoked discomfort in the Israeli art world. Moreover, her aesthetic affinity with Christian iconography as well as kitsch and the baroque, stood at odds with local artistic norms, and her diasporic style was perceived as undermining the Zionist ideal of the “new Jew.” The Zionist ideal of the “new Jew” envisioned a departure from the perceived weakness of the Diaspora Jew toward the figure of the sabra—constructed usually as a man embodying strength and autonomy. One year after Eshel-Gershuni’s solo exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, the institution presented the far more influential exhibition, titled Want of Matter, also curated by Breitberg-Semel. This exhibition established a thesis that shaped Israeli art for decades, privileging emotional restraint, intellectual aloofness, and material austerity—qualities aligned with the masculine ethos of the sabra. In this context, Eshel-Gershuni’s divergence was largely interpreted through a gendered lens and cast as the essentialized “feminine other.”

Eshel-Gershuni's contribution to the Israeli art field was to some extent recognized in 2009, when she received a Lifetime Achievement Award in Plastic Arts from the Ministry of Culture and Sport—a meaningful but less prestigious accolade than the Israel Prize. Despite this acknowledgment, her impact on the field has yet to be fully recognized. To date, no comprehensive research or scholarly exhibition catalogue has been dedicated to her oeuvre, influence, and contribution. The opening of a retrospective exhibition at the Mishkan Museum of Art, Ein Harod, in August 2025, accompanied by a forthcoming catalogue, may mark a decisive turn in positioning Eshel-Gershuni within the history of Israeli art, granting her the wider recognition that her bold and distinctive oeuvre has long deserved.

Azoulay, Ariella. Training for ART: Critique of Museal Economy. Tel Aviv: HaKibbutz HaMeuhad Publishing House and The Porter Institute, Tel Aviv University, 1999.

Bar Kadma, Emanuel. “Without Respect for Gold.” Yedioth Ahronoth, December 9, 1983. [Hebrew].

Breitberg-Semel, Sarah. “Bianca Eshel-Gershuni: The Blood Cycle.” In Bianca Eshel- Gershoni: 1980-1985. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum, 1985. [Hebrew].

Breitberg-Semel, Sarah. “Want of Matter as a Sign of Excellence in Israeli Art.” Hamidrasha, no. 2 (1999): 251–8. [Hebrew].

Carmi, Ayelet. “Sexism, Militarism and the Israeli Art Field: The Reception of Bianca Eshel-Gershuni.” Erev-Rav, April 24, 2022. https://www.erev-rav.com/archives/54191 [Hebrew].

Drutt, Helen W. “Three Days, Six Women, Four Tales.” In Women’s Tales: Four Leading Israeli Jewlers, edited by Alex Ward, Davira S. Taragin, and Helen W. Drutt. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2006.

Fischer, Yona. Bianca Eshel-Gershuni: Jewelry. Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1977.

Gladman, Mordechai. In a Silver Mirror: Bianca Eshel-Gershuni, Best of Her Work. Tel Aviv: HaKibbutz HaMeuhad Publishing House, 2007. [Hebrew].

Harel, Kobi. “Safety Pin.” Maariv, May 18, 1990. [Hebrew].

Kaferpik-Marcus, Michal.1993. “The Perfect Creatures of Creation.” Globes, April 19, 1993. [Hebrew].

Manor, Dalia. “Gold and Blood.” Studio, no. 11 (1990): 40–2. [Hebrew].

Ward, Alex. “Israeli Identity and Collective Memory.” In Women's Tales: Four Leading Israeli Jewlers, edited by Alex Ward, Davira S. Taragin, and Helen W. Drutt. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2006.

Interviews

"Bianca Eshel-Gershuni." Archive of the Future, 2024 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=409Qy_8W1mA

Shachnai Yakobi, Michal. “Bianca,” 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ssg5fgW8dXs