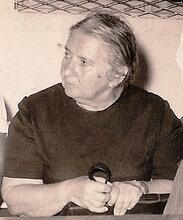

Bruria Benbassat de Elnecavé

Bruria Benbassat de Elnecavé (1915-2007) was born in Bulgaria into a middle-class Zionist family. After marrying her husband Nissim, they both lived on a kibbutz in Palestine until a disease forced them to leave and settle in Argentina in 1939. Once there, Bruria became involved with the local WIZO chapter, occupying various central positions in the organization. Without any formal educational training, and at a time when women were not often involved in activities outside of their homes and away from their families, Bruria travelled around Argentina and throughout Latin America helping to bring Zionism and Judaism to women. She remained active in Zionist circles until two years before her death at 92.

Family & Education

Bruria Benbassat de Elnecavé was born in Hascovo, Bulgaria, in 1915 but lived most of her childhood and teenage years in Plovdiv, the country’s second most important city after Sofía. Her parents Yom Tov Benbassat and Ester Bassan, a merchant and French teacher respectively, and younger siblings Bela and Shmuel spoke Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) at home and were all active in the large local Jewish community. Her parents were members of the B’nai Brith (a Jewish service organization founded in the United States with local branches around the world), and the children attended the local Jewish school instead of non-Jewish options her parents could have afforded, given their comfortable economic situation. At this school, Bruria cemented her Jewish and Zionist ideals: she became proficient in Hebrew and was introduced to Hashomer Hatzair (Young Guard), a Zionist youth movement that held activities in the afternoon in the school building. As a member of the movement, she learned about Jewish history, the geography of The Land of IsraelErez Israel, and the principles of the hechalutz movement that espoused Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah to A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim. At one of the camps organized by Hashomer Hatzair, Bruria met her future husband, Nissim Elnecavé, who at the time lived in Sofía but soon followed his parents to Argentina, where he was central to the development of the local chapter of the Hashomer Hatzair. After a few years of a long-distance relationship, the young couple married in Bulgaria in 1935 and prepared their move to Palestine.

To Palestine and Argentina

Life on the Bulgarian Tel Jai kibbutz was hard. During those difficult early years, in which the kibbutz was trying to figure out what to do to support itself, Bruria pruned orange trees, wrapped oranges to ready them for export, and worked as a dental assistant in Hedera, so that her salary contributed to the income of the kibbutz.

Although Bruria’s and Nissim’s dream had been to live as halutzim (pioneers) in Israel, they decided to leave in 1939 when Bruria developed a physical ailment that made life in those precarious conditions very trying. The couple joined Nissim’s family in Buenos Aires, Argentina. But Bruria felt alone and missed her family and friends in Palestine. She and Nissim therefore became active in Zionist circles. During her early years in the new country, while raising their children David (1939-2006) and Roland (1942-), Bruria joined a choir at the Chalom (an institution founded by Jews from Rhodes) and a Zionist organization called Acción Sionista (Zionist Action) that brought together both Sephardim and Ashkenazim, and eventually participated in the Consejo Juvenil Sionista (Zionist Youth Council).

WIZO Argentina

Feeling defeated at having had to leave Palestine and abandon her dream of kibbutz life, Bruria eventually decided, as noted in her memoirs, that “if I can be useful to an organization, it would be a mistake not to become involved.” Her association with the Argentina branch of WIZO began through the WIZO Sephardi chapter, which sought to spread the Zionist ideal among Sephardi women. She prepared and delivered public talks on Jewish and Zionist issues, and it was during one of these talks that the President of WIZO-Argentina invited her to join in the Executive Council as the Director of the Department of Culture. In this position, Bruria brought together the leaders of the departments of culture in the regional divisions to work together on their cultural plan. Under her leadership, the Department published educational booklets that discussed Jewish and Zionist topic, and organized various talks with both Jewish and local scholars, which increased the visibility of WIZO (and Zionism) in the local society. The material published by the Department of Culture was distributed among all centers in Argentina, as well as elsewhere in Latin America. Bruria also spearheaded two WIZO projects: a “Hebrew-Spanish” pocket dictionary (aimed at women travelling to Israel), and courses on the Bible (given the interest generated by the visit of a Bible scholar from Israel).

Bruria also engaged in a busy travel schedule to WIZO centers all over the country to give lectures and represent the executive committee during Jewish holiday and other events. While initially her husband drove her to the centers close to Buenos Aires, where she lived, she eventually ventured out alone, or took her mother (who had been living in Argentina since 1949) as her companion. To the rest of the country, she traveled alone, by train. Bruria also traveled throughout Latin America, in an effort to bring the WIZO centers closer and help them with their campaigns. Her husband seldom accompanied her on these trips outside of the country, and when he did, he jokingly introduced himself as “her secretary.”

Bruria’s activities deviated dramatically from ideals upper-middle-class women were expected to conform to. Her busy schedule inside and outside the country often clashed with her familial responsibilities. In her memoirs, she recalled the guilt she felt when her sixteen-year-old son Roland took himself to the doctor after a bad fall because she was leading a seminar; she had suggested ice and rest, but he ended up with his leg in a cast. “Even today,” she mused, “I ask how big our moral commitment to the cause of Israel was, how strong our willpower was, and how much passion had taken over this army of women to keep the Zionist ideal above all else.”

Bruria’s career at WIZO came to an end after nineteen years of continued work. But she was not done with her activism; she joined the B’nai Brith, where she was the president of two groups and active in the organization’s Political Action committee for more than 30 years, until 2005. She passed away in Buenos Aires in 2007, at the age of 92.

Bruria was a self-made woman who faced the challenges life put in front of her by thinking outside the box. She left her comfortable middle-class life in Bulgaria to work in Palestine, and when that did not work out, she dedicated her energy to fighting for the creation of the State of Israel. She belonged to a generation of female community activists who had no formal education in this area but understood the historical necessity of the times and learned by doing. She developed organizational and leadership skills, perfected her speaking and motivational abilities, and pursued her desire to bring Zionism to Jewish Argentines.

Elnecavé, Bruria. Crisol de Vivencias Judías. Buenos Aires: Ediciones La Luz, 1994.

Deutsch, Sandra McGee. Crossing Borders, Claiming a Nation: A History of Argentine Jewish Women, 1880-1955. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.