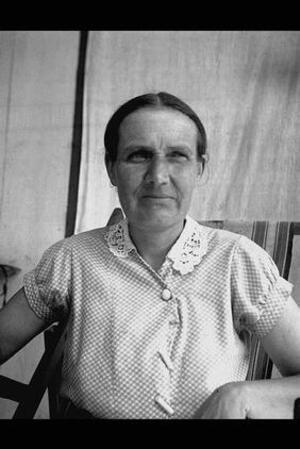

Elisheva Bichovsky

As one of Palestine’s first Hebrew poets, Elisheva Bichovsky (born Elizaveta Zhirkova in Russia) helped shape the country’s literary scene. She composed hundreds of Russian poems and published two collections in 1919 before switching to Hebrew and making aliyah in 1925. Her 1926 Kos Ketannah and 1929 Simta’ot were, respectively, the first poetry collection and first novel written by a woman to be published in Palestine. She earned a living from literary tours, during which the literary community in Palestine grew disenchanted with her. Following her husband’s death in 1932, she returned to Israel. She survived on a small stipend secured by the poet Bialik and on her translation work, but she never again wrote poetry.

Early Life and Family

Elisheva Bichovsky was a Russian poet and author who wrote in Hebrew. Elisheva, as she signed her work, was born Elizaveta Zhirkova in Riazan (Rayzan, 186 km SE of Moscow). Her father Ivan Zharkov, a village teacher who later became a publisher of textbooks, belonged to the Provoslavic Church, while her mother came from an Irish Catholic family whose patriarch had made his way to Russia during the Napoleonic Wars. After her mother died when Elisheva was three years old, she was raised by her mother’s sister in Moscow surrounded by English language and culture. There, she graduated from a girls’ high school and in 1910 trained as a teacher.

Hebrew Education

As Bichovsky recounted, she began to write poetry as an adolescent in the upper grades of high school (1907). During this period, she became friendly with a Jewish classmate who sparked her interest in Jewish culture and customs. In her memoirs, she recalls her first encounter with the Hebrew language through a Hebrew newspaper that she chanced upon. At first, she could not distinguish between Yiddish and Hebrew, for she saw them both as “the language of the Jews.” Initially, she studied Yiddish, which was easier for her since she already knew German. (She was able to teach herself the “square” Hebrew alphabet from a Hebrew grammar book owned by her brother, a philologist who was an expert in Oriental languages.) In 1913, Bichovsky began to study Hebrew at the evening classes of the Society of Lovers of Hebrew in Moscow. She studied on and off for two years, later continuing on her own by reading and speaking the language. From 1917 to 1919 she again lived in the city of her birth, Riazan, where a large number of Jewish refugees had gathered during the war, among them a young man who had studied at the Herzlia Hebrew Gymnasia, whom she “appointed” as her teacher.

Early Translations and Compositions

In 1915 Bichovsky began producing a number of translations from Yiddish to Russian that were published in the Russian-Jewish journal Evreskaya Zhizn (Jewish life). These included the short stories of Zvi David Numberg (1876–1927) and the poems of Judah Halevi (1075–1141) from Bialik’s Yiddish translation. She then turned her interest to Hebrew literature, where her first attempts at translation were from the stories of such contemporary Hebrew writers as Gershon Shoffman (1880–1972) and Joseph Hayyim Brenner (1881–1921).

Bichovsky composed roughly two hundred poems in Russian and a selection of these was published in 1919 in two collections, Minuty (Minutes) and Tainye Pesni (Hidden Songs). The outstanding theme of these poems was her sense of attachment to and longing for Jewish culture. In 1920 she married Simeon Bichovsky (1882-1932), a Zionist activist (and secretary of Dr. Jehiel Tschlenow, 1863–1918), teacher, literary critic and publisher, who was a close friend of Brenner and of Uri Nissan Gnessin (1879–1913) and helped them publish their writings. Also in 1920 she wrote her first poem in Hebrew, after which she ceased writing in Russian. Apparently influenced by both her first Hebrew teacher and her husband, she adopted Hebrew as her sole working language. While she had earlier signed her Russian poems with her Russian name Elizaveta, from this point forward she used the name Elisheva exclusively for all her Hebrew work. In the winter of 1925, the couple immigrated to Palestine with their young daughter Miriam (b. 1924), settling in “Little Tel Aviv,” not far from the Herzlia Hebrew Gymnasia.

Public Response

The fact that Elisheva was a non-Jewish poet who had left her people and her language to join the Jewish people in its emergent homeland was extremely moving for the Jewish public in Palestine. The literary community also received her with great enthusiasm, arranging readings of her works, which were published in every possible forum, to the point where her popularity aroused the resentment of the young poets (the Ketuvim [Writings] group, headed by Abraham Shlonsky, 1900–1973) and made her a target in their struggle against the older poets (the Moznayim [Scales] group, led by Hayyim Nahman Bialik, of which Elisheva was a member). But this period lasted only seven years (1925–1932), during which Elisheva produced the bulk of her Hebrew work in poetry, prose, essays and literary criticism; it was also during these years that most of her works were published, whether in the Hebrew press in Palestine (Moznayim, Do’ar ha-Yom) and abroad (Ha-Tekufah, Ha-Toren, Ha-Olam), or in books published by her husband’s publishing house, Tomer. These included: Kos Ketannah (A Small Cup; poems, 1926); Sippurim (Stories, 1928); Haruzim (Rhymes; poems, 1928); Mikreh Tafel (A minor incident; a story, 1929); Meshorer ve-Adam (Poet and man; essay on the poetry of Aleksandr Blok, 1929); Simta’ot (Alleys; novel, 1929); and Elisheva: Kovez Ma’amarim odot ha-Meshoreret Elisheva (Elisheva: Collected articles about the poet Elisheva, 1927), which appeared in several editions in Tel Aviv and Warsaw. Kos Ketannah was the first book of poems by a woman poet to be published in Palestine and Simta’ot the first novel by a woman.

Challenges in Later Years

The couple nonetheless found themselves in difficult financial straits and to her great regret Elisheva was forced to leave her husband and daughter on more than one occasion and embark on a tour of Jewish communities in Eastern and Western Europe. There, she gave readings from her poems and stories at special literary evenings (during the summer recess, her husband and daughter would accompany her). In the summer of 1932, in the midst of such a tour in Kishinev, her husband passed away suddenly. Elisheva returned to Tel Aviv, her whole world collapsing around her. In addition to the tragedy of her husband’s death, she was suddenly snubbed by the community. Her attempts at earning a livelihood (among other things, as a librarian at the Sha’ar Zion Library) were unsuccessful. She moved into a rundown shack on the edge of Tel Aviv, where she was saved from starvation by Bialik, who interceded to secure her a modest stipend from the Israel Matz Foundation in New York ($15 a month). Bitter and hurt, she cut herself off from literary society. From 1932 until her death in 1949 she ceased publishing her work; her other efforts, in the field of translation, she considered unimportant. In the spring of 1949 she was supposed to travel to England to visit her daughter Miriam Littel (who served in the ATS in Egypt during World War II and in 1946 married a British soldier by whom she had three daughters). Since she was feeling unwell her friends from Devar ha-Po’elet helped pay for a visit to the hot springs in Tiberias, where she died of cancer on March 27, 1949. Because she had never converted to Judaism—a fact that she always stated openly—difficulties arose as to the place of burial. Only upon the intervention of the chairman of the Writers’ Association was it agreed to bury her in the cemetery of Kevuzat Kinneret, next to the grave of the poet Rahel (Bluwstein).

Poetic Style and Literary Influence

Bichovsky was raised on the poetic schools of Futurism and Acmeism, which developed in Russia in the early twentieth century, supplanting the Russian Symbolist movement of the late nineteenth century. Her poetry is associated primarily with the Acmeist school, which advocates short lyrical poems phrased simply, clearly and melodically, reminiscent of a painting with rapid brush strokes and a fragile, aesthetic line. “My poetry is brief, a cloud in the sky,” in Elisheva’s words; nonetheless, she also incorporates anti-Acmeist elements, for example, a longing for the mysterious and dreamlike, or a reference to Symbolist expressions. These elements are the consequence of a conflicted, questioning worldview at the center of which lies a profound sense of alienation (“I had no mother, I will have no son”), while at the same time there is a relentless longing for an unidentified metaphysical entity (“a god without name”) that can promise her vitality and happiness as a human being and an artist. This melancholic spiritual confession, which does not commit itself to any specific religion, also frames her poetic space as an endless pilgrimage of wandering and despair—a journey embarked on with the clear knowledge that no utopian “land of Avalon” awaits her at its end (“All my soul yearns/for the land of false hopes”).

Needless to say, this sense of a conflicted state of existence—between a reality of abandonment and exile on the one hand, and the pursuit of a promised land on the other, between the “gray day” of the secular and the “enchanted night” of the sacred—draws Elisheva closer to the Jewish people. She identifies her fate with theirs: “Only on the setting sun will my eyes gaze/Only on the Eastern Star—your heart’s lament/Who will say to us all that there is no Homeland?” (“Galut,” Toren 57).

Thus it is not surprising that Bichovsky connected with Zionist Jewish circles in particular, nor that she chose to immigrate to Palestine, which for her represented the source of creativity and inspiration: “When it seems to me at times that the wellspring of my poetry has run dry, I am struck by the feeling: There, in the land of beauty, the Divine Presence will shine on me once more.”

Bichovsky’s poetic oeuvre can be divided geographically, into Russian and Palestinian chapters; not so her prose, which deals solely with the reality of the early decades of the twentieth century in Russia. It should be noted here that her transition to prose was inspired by the poet Aleksandr Blok, whom she regarded as her greatest teacher (“… more than ‘simply’ a poet … he is the essence of our life”). In her essay Meshorer ve-Adam, she examines his writing, stressing his uniqueness, which stems from a dynamic of expansiveness that constantly leads him to a different poetic experience (thematic, genre-related or formative) and, at the very least, avoids creative stagnation. Bichovsky adopted this challenging principle, expanding her horizons from the lyric poem to the short story, and from the lyrical short story to the realistic novel.

Each of her six short stories revolves around a woman who speaks of herself in the third person, against the backdrop of her own life story and environment. And although the setting differs from story to story, all of the protagonists seem drawn from the same “confessional I” that is so dominant in Bichovsky’s poems as well. It is the portrait of a woman unable to communicate with those around her; amid the conflict between herself and her surroundings, she constructs—in a manner unique to her—her own inner spiritual dream-world, which she inhabits with intensity (“Yamim Arukim” (Long Days); “Ha-Emet” (The Truth). This imaginary spiritual world also reinforces the Jewish-Christian conflict, which is expressed primarily within the framework of male-female relationships (Jewish woman/Christian man—“Malkat ha-Ivrim” [Queen of the Hebrews]; Christian woman/Jewish man—“Nerot Shabbat” [Sabbath candles]), which refers to Bichovsky herself: “Because I have two souls—one Russian and one Hebrew.”

This conflict is further developed in her novel Simta’ot, which deals with Moscow of the early 1920s, during the brief period when Lenin was in power and attempted to restore the collapsing Soviet economy. Elisheva offers us a glimpse into Moscow’s bohemian scene at this historical juncture, with its mélange of men and women, Christians and Jews, engaged in the various arts; through them, she examines the cultural-political upheaval of post-revolution Russia, combining feminist tendencies on the one hand with Zionist leanings on the other. There is no question that through this novel Bichovsky contributed thematic constructs previously unknown to Hebrew literature in both Palestine and the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora: a depiction of the “new woman” of the post-World War I era; the self-portrait of woman-as-creator; and the dialogue between Christians and Jews, as seen from a non-Jewish perspective.

Contribution to Modern Hebrew Poetry and Prose

Bichovsky was received with ambivalence by the Jewish public in the Diaspora and in Palestine. On the one hand, Jews were flattered by her decision to work in Hebrew (“the language of the heart and of twilight,” as she put it); not without reason was she referred to as “Ruth from the banks of the Volga” (in an allusion to the biblical Ruth the Moabite). On the other hand, there were critics who attacked the quality of her writing and the level of her Hebrew, arguing that her work was highly overrated. Not so today. A fresh reading of her work, especially from a feminist perspective, reveals a creative diversity that enriched modern Hebrew poetry and prose with a feminine voice all its own—a voice that offered not only content and range but an inner rhythm with its own unique meter and cadence. At a time when the majority of poets based themselves on the Ashkenazic pronunciation of the Diaspora, she was one of the first to accentuate her verse according to the Sephardic stress on the final syllable (which eventually became the dominant form in Palestine and, later, in Israel). As she explained (in 1927): “I can point to but one goal in my work—to aid as much as possible in the development of Hebrew poetry in the Hebrew language that we speak among ourselves every day with the Sephardic pronunciation. Therefore I have refrained from all experimentation and pursuit of new forms or innovations in my poetry, because first and foremost I want to see Hebrew poetry that is vital, natural and inextricably linked with our language and our lives.”

Selected Works by Elisheva Bichovsky

Hebrew

Elisheva. From My Memoirs. Elisheva Archives, Genazim (7863/5), Saul Tchernichowsky House, Tel Aviv.

Toren, Haim, ed. Elisheva: The Collected Poems, with an introduction by Haim Toren. Tel Aviv: 1970, 9–16.

Arnon, Yochanan. “Our Sister Elisheva.” Et Mol (July 1978): 41–42.

Barzel, Hillel. Elisheva and Her Novel Simta’ot. Tel Aviv: 1977, 280–298.

Berlovitz, Yaffah. “Ruth from the Banks of the Volga.” Maariv Literary Supplement, June 8, 2000, 27.

Berlovitz, Yaffah. “Round and Round the Garden: Mikreh Tafel and Five Other Stories.” Davar, April 22, 1977, 16.

Elinav, Rivka. Women and the Tree of Knowledge: The Intellectual Heroine in Hebrew Women Women’s Prose – A Literary and Feminist Study in the Prose of Elisheva (Bichovsky) and Lea Goldberg (“Ki marah me’od hada‘at: Hagiborah ha’intelektu’alit-yotzeret besiporet shel Elisheva [Biḥovski]). Tel Aviv, 2012.

Elisheva: Collected Articles about the Poet Elisheva. Warsaw and Tel Aviv: 1927.

Kinel, Shlomit. “I Had No Other World, No World of My Own” (Lo hayah li shum ‘olam aḥer, shum ‘olam misheli). Haaretz, Culture and Literature Supplement, June 12, 2008.

Kinel-Limoni, Hila Shlomit. Aliens and Rebels: Female Fiction in the Hebrew ‘Revival’ Literature: Hava Shapiro, Dvora Baron and Elisheva Zirkova-Bichovsky (Telushot vemoredot: Siporet nashim besifrut hateḥiyah ha‘ivrit: Ḥava Shapira, Devorah Baron ve’Elisheva Z’irkova-Biḥovski). Tel Aviv, 2016.

Kornhendler, Shulamit. “The Principle of Expansion of the Genre in the Work of Elisheva” (Hebrew). Master’s thesis, Bar-Ilan University, 1999.

Meron, Dan. Founding Mothers, Stepsisters. Tel Aviv: 1991, 25–33, 103–104, 154–155.

Rattok, Lily, ed. Every Woman Knows It: An Afterword.” In The Other Voice: Hebrew Women’s Literature. Tel Aviv: 1994, 268–269, 336–337.

Meron, Dan. “Revisiting Elisheva (Bikhovsky) – Part I” (Sha‘atah shel Elisheva – Ḥelek rishon). Iyunim: Multidisciplinary Studies in Israeli and Modern Jewish Society, 12 (2002): 521–566.

Meron, Dan. “Revisiting Elisheva (Bikhovsky) – Part 2” (Sha‘atah shel Elisheva – Ḥelek sheni), Iyunim: Multidisciplinary Studies in Israeli and Modern Jewish Society, 13 (2003): 345–392.

Olmert, Dana. “Gender Conformism and Its Poetic Implications: The Story of Elisheva” (Konformiyut migdarit vehashlakhoteiha hapo’etiyot: Sipurah shel Elisheva). In The First Hebrew Women Poets: Predicaments of Writing and Loving (Bitenu’at safah ‘ikeshet: Ketivah ve’ahavah beshirat hameshorerot harishonot). Tel Aviv, 2012, pp. 199–209.

Rav-Hon, Orna. “The Confessional Model in the Work of Elisheva.” Master’s thesis, Tel Aviv University, 1989.

Shaked, Gershon. “Elisheva Bikhovsky (Zhirkova).” Hebrew Literature, 1880–1980, vol. 3, 87–93. Tel Aviv/Jerusalem: 1988.