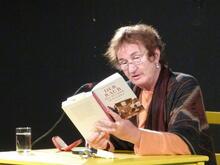

Esther Dischereit

Esther Dischereit grew up in post-war West Germany, the daughter of a mother who survived the Holocaust in hiding and a German father. After her parents’ divorce and her mother’s death she lived with her father and his new family. Her participation in the political unrest of 1968 prevented her from teaching in public schools. She apprenticed as a typesetter and worked in print shops, becoming active in the trade unions. After German reunification in 1989 she moved to Berlin with her two daughters and became a full-time writer, performer, and teacher. She is a critical observer of multi-cultural German society and serves as an intermediary especially between Germany and the United States.

Early Life, Family, & Education

Esther Dischereit's childhood, and indeed her entire life, were marked by the survival in hiding during World War II of her mother, Hella Freundlich. During the war, Freundlich hid at many different addresses in Berlin and was helped by many people, especially a railroad worker who pretended to be her husband. After the war, Freundlich remarried a non-Jewish German physician, Paul-Jürgen Dischereit. Together they had two daughters, the younger of whom was Esther, born on April 23, 1952, in Heppenheim in Southern Hessia. Her first born, who also survived the Shoah, lived with them.

Dischereit’s parents divorced when she was seven and the children lived with their mother. She saw to it that they were instructed in Jewish religion and customs. They attended Hebrew school in Darmstadt, and on Friday evenings a rabbi visited their home. But the Jewish community changed. Newcomers from Eastern Europe became predominant; the children did not understand the languages of the Eastern European immigrants and felt estranged. After a few years the visits in Darmstadt ended, and with them any further connection with the Jewish community.

When Dischereit was fourteen, her mother died, and the children subsequently lived with their father and his new family. Dischereit completed gymnasium (high school) in record time. After getting a degree in education in 1973, she wanted to become a teacher, explaining, “Children are all that counts for me.” Indeed, her first book was a children’s book. But she had come of age with the rebellious 1968 generation and had been active as a student in the “Red Cells,” which prevented her from teaching in public schools. Instead, she apprenticed as a typesetter and worked for several years in print shops, becoming active in workers’ councils for trade unions. In 1987 she went to South Korea to study working conditions, especially of women.

Dischereit’s first daughter was born in 1983 and her second daughter in 1989. She moved to Berlin in 1989, and after the Berlin Wall came down that year, she participated in a political art project in East Germany. For several years she continued to work as curator in this venue, developing political art concepts and managing the website “Respect.” The elimination of her position sparked public protests. After losing her job, she taught contemporary German literature and German as a second language in the in the Berlin program of New York University.

Over time, writing became an expanding part of Dischereit’s life. Inspired by her mother’s experience as young woman with a child persecuted and in mortal danger, she devoted her life and her writing not only to depicting victims of many kinds but also to protestingt hate and social injustice in many forms.

Among the small but growing number of Jewish writers in Germany, Dischereit stands out through her prolific production in a wide spectrum of genres: novels, stories, essays, poetry, plays (including “Hörstücke,” or radio plays), opera libretti, sound installations, and concept art. Since 1988, she has collaborated with musicians and dancers. Together with Ray Kaczynski, a Detroit percussionist and composter, she founded the CD label “wordmusic.”

Jewish Identity in Dischereit's Writing

Being Jewish is the predominant topic of Dischereit’s early writings, for example in her prose works “Joemi’s Tisch” (Joemi’s Table, 1988) and “Merryn” (1992). The latter is an elliptic work with fragmented shifting perspectives and time levels, “as if someone were speaking with an open mouth and the words don’t want to come out.” In her essay collections Übungen jüdisch zu sein (Exercises in being Jewish, 1998) and Mit Eichmann an der Börse: In jüdischen und anderen Dinge” (At the Stock Exchange with Eichmann: On Jewish Matters and Other Things, 2001), Dischereit’s voice is that of the second and third generation of children of Holocaust survivors living as a minority in Germany. Her predicament involves knowing she is Jewish but not knowing many things Jews and non-Jews expect of her. “Never been to Israel! Oh, my God!” she writes ironically in Übungen jüdisch zu sein. But she lights the Yahrzeit candle for her mother because she saw her mother lighting the candle for her own mother.

In many essays and newspaper articles, Dischereit also focuses on antisemitism, as in her commentary on the debate between the German author Martin Walser (b. 1927) and the President of the German-Jewish Congress, Ignatz Bubis (1927-1999), on whether to put an end to the discussion of the Holocaust in the German media, which Walser demanded. (“M. Walser,” 1998).

On Being a Woman and an Intellectual

In her writing, Dischereit also reflects on what it means to be a woman and an intellectual. In the stories in Der Morgen an dem der Zeitungsträge” (In the Morning when the Newspaper Boy, 2007), Dischereit presents herself as an entirely new and highly literary writer. In a detached almost laconic language, she shows a single woman in various everyday situations and more or less accidental encounters.

As a young union member, Discherheit didn’t let herself be shut out of women’s committees which published proclamations on world peace and other lofty goals. She was not afraid of contradicting her colleagues, and comments “I was interested in wages.” While employers rejected her union activities, union member rejected her as an intellectual.

A Rhythmic Poet

According to Dischereit, she was able to become a writer only after abandoning the political perspective of the 1968 neo-communist movement. In a 40-page essay, “Die Linke und der Antisemitismus oder warum ich das Thema nicht mochte” (The Left and Antisemitism, or Why I Disliked the Topic), she declares that she was able to free herself from ideological constraints only after writing nothing but poetry for one year.

In Dischereit’s first poetry collection, “Als mir mein golem öffnete” (When my golem opened for me, 1996), body and intellect, eroticism and spirituality are closely related, even interlocked. In the second, “Rauhreifiger Mund” (Hoarfrosted Mouth, 2001), she is no longer an explicitly Jewish poet writing from a minority perspective in an environment where relationships with the majority have an additional and ultimately unbearable weight. These poems are situated in a wintry city- and landscape. Their sparse language is nevertheless filled with light. Dischereit’s love poems are never sentimental. After the poetry volume “Im Toaster steckt eine Scheibe Brot” (There is a Slice of Bread in the Toaster, 2007) Dischereit published “Sometimes a Single Leaf” (2019), a collection of earlier and new poems translated by Iain Galbraith. She renounces rhyme and meter, preferring instead short free verse that creates its own lively rhythm. She is a “rhythmic” poet.

Radio Plays, Sound Installations, Concept Art

Dischereit’s rhythmic musicality is also evident in her radio plays, many with percussion accompaniment, which form an important part of her oeuvre. Here, two to five voices, mostly of women, serve as “carriers of history,” not necessarily contemporary history, as in “Gertrud Conners” (1998). Conners is a former East German dissident living in West Berlin, where her situation is anything but privileged. “Mellie” (2003), on the other hand, is a minimalist experiment in which the poet’s voice, electronic music, and text fragments, including quotations from Dischereit’s poetry, produce an extraordinary combination of sound and text, an “inner monologue” of moments remembered and present in a woman’s life.

The next step in the development of Dischereit’s extraordinary work consisted of sound installations in public spaces, such as “Eichengruen” (2009). In a square of the Northern German city of Dülmen, people hear music and 55 poetic texts from Dischereit’s collection “Vor den Hohen Feiertagen gab es ein Flüstern und Rascheln im Haus” (Before the High Holidays There was Whispering and Rustling in the House 2009), which evoke the life of Jewish citizens in Dülmen. While “Eichengruen” is a permanent installation, Dischereit has also created non-permanent concept art, such as in “Particles of the Child with the Big Face” at Museumsquartier Vienna. The work was conceived with students and actors in conjunction with the “Vienna Project” about remembering and forgetting (Vienna 2013/2014).

The Voice of Victims

Dischereit’s current work centers on antisemitism and racism and the inclination of people to turn away and to forget injustice. She wants to give victims a voice. One catastrophic injustice in the recent past was the killing of nine Turkish immigrants, mostly small business owners, and a German policewoman, by the self-proclaimed “National Socialist Underground” (NSU) between 1998 and 2007 in several German cities. Instead of following leads from the Turkish community and families of victims, the authorities looked for the killers within the Turkish community itself. It took seven years of investigating and a five-year court trial to expose the abysmal failure of the authorities, who did not search for the perpetrators among Far Right groups. Dischereit finds it “remarkable” that the faces and lives of the murderers became well known but not those of the victims. The public saw them just as Turkish, not as fathers and brothers, neighbors and colleagues. Dischereit gives the dead a voice in “Blumen für Otello. Klagelieder. Über die Verbrechen in Jena” (Flowers for Otello. Lamentations. About the Crimes in Jena), an eclectic book containing poetry (“Lamentations”), and opera libretto (“Flowers for Otello”), and documentation including witness reports and court documentation from the NUS trial. “Otello” can be considered the summation of her work to date, and “Lamentations” her strongest poetry. She lets a mother, a brother, and a neighbor speak. Each voice is unique, whether suffocating in grief or simply recalling an everyday heartbreaking detail. The center of the work is a libretto that recalls the prejudices and blunders of many government agencies. Dischereit’s status as observer of a parliamentary committee investigating the NSU crimes provided her with a wealth of documentation that concludes this extraordinary book.

Speaker and Teacher

Esther Dischereit is also a sought-after speaker, commentator, contributor to political publications, and teacher. Her professorship at the Universität für Angewandte Kunst (University of Applied Art) in Vienna from 2012 to 2017 resulted in numerous publications of projects with her students, such as “Ich möchte, dass es mich etwas angeht – I want it to be my concern” (German and English, 2015). Dischereit travels worldwide, reading, performing, and lecturing. She finally travelled to Israel and gave readings in the West Bank. In 2004, the University of Swansee held a conference on Dischereit’s work that resulted in a substantial volume of papers. She was Poet in Residence at Oberlin College and the University of Wisconsin-Madison 2013 and DAAD Chair of Contemporary Poetics at New York University in 2019. Several of her radio plays have won awards. In 2009 she won the Erich Fried prize for her life’s work.

Esther Dischereit also reports about the United States in German media, thus serving as an intermediary between the two countries. Her enlightening voice in a sober tone speaks to many audiences.

Selected Works

Joëmis Tisch. Eine jüdische Geschichte (1988); English “Noëmi´s Table,“ in Contemporary Jewish Writing in Germany. An Anthology. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Merryn (prose, 1992).

Als mir mein golem öffnete (When my golem opened for me, poems 1996).

“Gertrud Conners (radio play, 1997).

Übungen jüdisch zu sein (Exercises in Being Jewish, essays 1998).

Mit Eichmann an der Börse. In jüdischen und anderen Angelegenheiten (2001).

Rauhreifiger Mund (Hoarfrosted Mouth, poems 2001).

“Sommerwind und andere Kreise“ (Summerwind and Other Circles, radio play 2002).

“Mellie“ (radio play 2003)

“Ein Huhn für Mr. Boe“ (A Chicken for Mr. Boe, radio play 2003).

“Vor den Hohen Feiertagen gab es ein Flüstern und Rascheln im Haus” (Before the High Holidays There was Whispering and Rustling in the House (2009).

“Blumen für Otello. Klagelieder. Über die Verbrechen von Jena“ (Flowers für Otello. Lamentations. About the Crimes in Jena). Türkish translation. by Saliha Yeniyol (2014).

“Großgesichtiges Kind/The Child with The Big Face.“ English translation by Iain Galbraith (2015).

“Ich möchte, dass es mich etwas angeht. Die Suche nach Erinnerung.“ (I want it to be my concern. In Search of Memory. Ed. With Ferdinand Schmatz 2015).

Podcast on Coronavirus, https://www.goethe.de/en/kul/ges/eu2/pco/dan/21856139.html.

Brungs, Juliette. “Performing the Jewish Body in Contemporary Germany.“ PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 2013.

Costazza, Allessandro. “ Tra Zakhor e Purim: ‘Esercizi per essere ebrea‘ in Joëmis Tisch. Eine jüdische Geschichte" di Esther Dischereit.“ In Il mio cuore è a oriente. Studi di linguistica storica, filologia e cultura ebraica dedicati a Maria Luisa Mayer Modena. Milan: Cisalpino, 2008.

Gilman, Sander, ed. Reemerging Jewish Culture in Germany. New York: New York University Press, 1994.

Hall, Katharina, ed. Esther Dischereit. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2007.

Lezzi, E. G“eschichtserinnerung und Weiblichkeitskonstruktion bei Esther Dischereit und Anne Duden.“ Aschkenas 1 (1996).

Lorenz, Dagmar C. Keepers of the Motherland. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

Schruff, Helene. Wechselwirkungen. Deutsch-jüdische Identität in erzählender Prosa der zweiten Generation. G Olms, 2000.

Serup, Martin Glaz Kulturel rindring og konceptuel vidnesbyrdlitteratur. Ein unbekannter Platz wird Eichengrün-Platz genannt. PhD Diss, University of Copenhagen, 2015.

Shedletzky, Itta. “Eine deutsch-jüdische Stimme sucht Gehör.“ In In der Sprache der Täter, edited by Stefan Braese. Springer, 1998.