Rachel Cowan

Rachel Cowan, Rabbi and leader in Jewish healing.

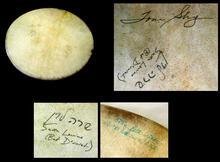

Courtesy of Rachel Cowan and the Waters of Eden, San Diego Community Mikvah and Education Center

Rabbi Rachel Cowan left a meaningful mark on New York’s Upper West Side, Israel, and the Jewish community as a whole. Through civil rights activism in the 1960s, she met her future husband Paul Cowan, thus beginning her involvement in Jewish life in the following decades. As one half of an interfaith marriage, Cowan helped to destigmatize interfaith families, and she worked hard to make Judaism more accessible to those not born into it, even before her conversion and later ordination as a rabbi. Cowan worked at a plethora of Jewish institutions, several of which she helped found, and fostered non-mainstream expressions of Judaism within Israel.

Early Life and Early Activism

Rachel Ann Brown was born on May 29, 1941, in Princeton, NJ, and grew up in Wellesley, MA. Her father, Arthur A. Brown, a direct descendant of the Mayflower, was a Rhodes Scholar and operations research analyst. Her mother, Margaret Warren Brown had Puritan roots and was an innovator in creating children’s school libraries (over 100 in the Boston Public Schools).

With her two younger sisters and one younger brother, Rachel was raised in the Unitarian Church and the Quaker tradition devoted to community, humanity, a life of service, and attention to nature’s gifts. She reflected years later that quiet moments of communal prayer and silence while attending summer camp and sitting alongside the lake planted the seeds for her pioneering work in Jewish Mindfulness practice.

Rachel majored in sociology at Bryn Mawr College and graduated in 1963. She and her sister Connie joined the Freedom Riders, tutoring children to begin to integrate schools. There she met Paul Cowan, son of an affluent but assimilated Jewish family. When Rachel and Paul realized they were both headed for graduate school at the University of Chicago, where she woud study at the School of Social Service Administration and he with the Committee on Social Thought, they drove in a two-car caravan, stopping at many Howard Johnson restaurants along the long ride. As Paul’s brother Geoff shared at Rachel’s funeral, by the time they reached Chicago, they were in love.

Rachel and Paul married in 1965. Following their graduations, they spent a summer registering Black voters and then left for the Peace Corps in Ecuador. Rachel used her skills as a social worker, and she had developed a love for photography that she explored as a hobby in Ecuador. As Geoff commented at Rachel’s funeral, “Paul and Rachel were in Mississippi in 1964, registering black voters: Rachel was in Jackson that summer, and Paul was in Vicksburg. Some of you knew Paul and Rachel from their years in Guayaquil, Ecuador, the years that Rachel described in Growing Up Yanqui and Paul chronicled in The Making of an Un-American. How many couples write companion memoirs? And how many manage to get both published?”

The Road to Jewish Life, Renewal, and Leadership

After returning from Ecuador in 1968, the Cowans settled in New York City. Paul worked as a journalist for the newspaper The Village Voice, while Rachel worked for the Scientist’s Institute for Public Information, took photographs of her own and to illustrate Paul’s articles, and worked with Paul in writing. When their children Lisa and Matthew were born in 1968 and 1970, Rachel was instrumental in founding the Upper West Side day care parent cooperative known as the Purple Circle. As their children grew, Rachel and Paul looked for a suitable Jewish afternoon school and help found the New York Havurah’s afternoon school. As half of a young intermarried couple, Rachel pushed for inclusivity in the Jewish community, co-authoring with Paul the groundbreaking book Mixed Blessings: Overcoming the Stumbling Blocks in an Interfaith Marriage (1987).

When Paul’s parents were killed in a tragic fire in 1976, Paul and Rachel were comforted by the Havurah Community as well as by Rabbi Singer, an orthodox rabbi on the Lower East Side about whom Paul had been writing for the Voice. These developments moved Rachel to convert to Judaism in 1980 under the auspices of Conservative Rabbi Wolfe Kelman.

Every inflection point in Rachel’s life became a source of mission and activism. In the early 1980s, she was pivotal to the revival of New York’s Congregation Anche Chesed, becoming its Executive Director. Together with others, including Paul Cowan, Rabbi Wolfe Kelman, Sharon Strassfeld, and Michael Strassfeld, she shaped Anche Chesed into a model of a multi-community approach under one roof, with a number of day care programs; they also completely renovated the sanctuary to create a more intimate and collective space and founded a Learners Minyan, helping those unfamiliar to Jewish practice learn and experience prayer in a warm and accessible way.

Nine years after converting to Judaism, Rachel was ordained as a rabbi in 1989 by the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.

Rabbi Cowan used her dual perspective as both outsider and insider to sense what was needed in the Jewish world. As she recalled in an address at the ordination of HUC’s class of 2011:

I had the great fortune to meet Paul Cowan—to be entranced when he told me he worked for civil rights because he was a Jew—and to marry him (in 1965). Over the course of the next 15 years, raising two children, and making a home on the Upper West Side, we were drawn into Jewish life, and I to converting. Thereafter, I became deeply involved with the people revitalizing the then-comatose congregation Ansche Chesed, and was inspired to apply to rabbinical school. I was attracted to HUC for its emphasis on social justice, outreach, and the emerging feminist consciousness amongst the women rabbis… We did not speak of the presence of God, the experience of prayer, or the inner life in those days.

In Rachel’s last year of rabbinical school, tragedy struck again when Paul died in 1988 at the age of 48. During his illness, Cowan discovered to her dismay how few Jewish materials and support systems there were for the sick and dying. Here too, she became motivated to act.

The Cummings Years and IJS

After Cowan’s ordination in 1989, she began working for the Nathan Cummings Foundation, founding its Jewish Life Initiative. She also taught for “Derech Torah” at the 92nd St Y, a program that welcomed interfaith couples to explore Judaism together. At Cummings, Cowan took the lead in searching for sparks of Jewish Renaissance all over the world. With the former Soviet Union in transition, she supported emerging projects. She also shepherded the beginnings of numerous initiatives in the United States, including collaborating with the JCC of Manhattan to create a meditation program, which eventually became a special room devoted to this practice when the building was finished. In 1990, she established the Jewish Healing Center to support those ailing, healing, and tending the sick.

At Cummings, Cowan played a unique role in the emerging Israeli Jewish Renaissance. As a foundation professional, she had the capacity to provide financial assistance to creative initiatives in Israel. A good portion of her activities was connecting to new expressions of Jewish culture and spirituality growing in Israel. Cowan identified a real thirst for alternative expressions of Judaism, particularly among second- and third-generation Israelis. She traveled to Israel on a regular basis and searched for new ideas. And she found them among (mostly) young Israelis who broke out of the rigid Orthodox/secular divide, who were looking for something else in text study, ritual, community-building, and Jewish peoplehood. Cowan commissioned research projects and stimulated the creation of coalitions and partnerships. She midwifed the founding of Panim, the first cross-denominational and umbrella coalition for the Israeli Jewish Renaissance. Her efforts supported the Midrasha at Oranim (an educational center working towards the renewal of Jewish life in Israel), Kolot (a beit midrash that takes a pluralistic approach to studying Jewish texts), and more. But Cowan was not a typical philanthropic foundation grant officer. She was a total person, who immersed herself in subjects she humbly supported. With her charming contemporary Hebrew, she made deep friendships with a whole of Israeli Renaissance activists and leaders. She midwifed a range of initiatives that paved the way for the robust pluralistic Jewish scene active in today’s Israel.

After working at Cummings for fourteen years, Cowan took her experience, insight, and vision and founded the Institute for Jewish Spirituality in 2000. Just as she had understood years earlier that Jewish healing was essential to the community, now she knew that well-being was no less important. Working with her close colleague and friend Rabbi Nancy Flam, and later with Rabbi Sheila Weinberg, they created a retreat and enrichment program, first for rabbis and eventually for cantors and laypeople. The Institute combined techniques of mindfulness, nigunim (Hasidic melodies), yoga, and Hasidic text study, enveloped in hours of silence to allow for deep inner work and calm. Participants took part in four five-day retreats over a year and a half; in between retreats, they worked with a study partner to practice and sustain the work of spiritual wellness. The IJS’s impact on clergy and laypeople has been immeasurable, transforming Prayertefillah, ritual, and Jewish study throughout congregations and Jewish institutions.

Around the same time, Cowan started leading meditation services in New York City with Rabbi Marcelo Bronstein at Congregation B’nai Jeshurun Together they taught classes about Jewish meditation, called “Creating Space for the Contemplative,” for more than 20 years. As Cowan later reflected in her 2011 ordination address at HUC, “In this work, I discovered the concept of spiritual practice and ways to cultivate it. By practice, I mean daily activities that cultivate qualities of mind, soul, heart and body, that are experiential, accessible, helpful—not simply intellectual, or rote."

Cowan stepped down as Director of IJS in 2011, although she stayed on as a staff member. As she faced aging and semi-retirement, she and Linda Thal began giving workshops and sessions on “Wise Aging”; these workshops became her next book with Thal, Wise Aging: Living with Joy, Resilience, & Spirit (2015). Once again, Cowan’s lived experience became a passion to guide others.

Increasingly Cowan gave her time and energy to Congregation B’nai Jeshurun, leading monthly Friday night Kabbalat Shabbat Meditation and Nigunim services with Rabbi Marcelo Bronstein, as well as other spiritual retreats. After her death, a chapel was dedicated to her memory at BJ.

Cowan also turned her energies beyond the Jewish community. She became more involved as a board member of The Brotherhood/Sister Sol, a community organization in Harlem providing multi-layered support services and leadership programs for youth.

Aging and Dying

Rachel Cowan was diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer, in the spring of 2017. With a very grave prognosis, she made the decision to teach us how to die with equanimity and gratitude. It was her last gift while she was alive. During this time, filmmaker Paula Weiman-Kelman made a documentary about Cowan. Dying doesn’t feel like what I am Doing followed Cowan’s story, celebrating her life and legacy. In addition, photographer Frederic Brenner brought together her loved ones for two photographs. The first, on her bed, assembled the many guests who had stayed at her home. (Rachel had for years been the place to stay for friends, family, friends of friends, colleagues, and especially Israelis she had promoted and supported long after she left Cummings.) The second photo was at B’nai Jeshurun, where her family and friends gathered around her to celebrate her life.

In these last years, Cowan had more time for her greatest passion: her four grandchildren. She also devoted mornings to bird watching and summer to kayaking in Alaska.

Marvin Israelow, a member of the board member of IJS, said this at Cowan’s funeral:

In April, shortly after Rachel’s MRI indicated that her tumor was unresponsive to treatment, her dear friend and medical advisor, Dr. Julia Smith, shared a perspective that gave Rachel a way to frame her remaining time. First, she told Rachel, “You’re not dying; you’re living with a terminal illness.” Rachel, up until her last breath, was never dying. She was always, as our tradition teaches, choosing life, choosing to live.

Rabbi Rachel Cowan died on August 31, 2018, at the age of 77. Her biography and legacy are a remarkable story of compassionate leadership. She ignited the inner light of countless students and fellow seekers, modelling intentional listening, spiritual direction, and myriad practices of prayer, silence, mindfulness, and nature walks, seeking the balance of body and soul, mind and spirit. She never lost her New England patrician stature, but she wedded it with Jewish soulfulness, and a tremendous ability to find joy and share love with so many.

Selected Works by Rachel Cowan

Growing up Yanqui. New York: Viking Press, 1975.

Wise Aging: Living With Joy, Resilience, and Spirit (witih Linda Thal). Springfield, NJ: Behrman House, 2015.