Cookbooks in the United States

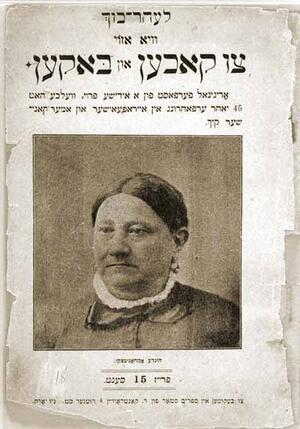

Hinde Amchanitzki's Lehr-bukh vi azoy tsu kokhen un baken (Textbook on How to Cook and Bake), published in New York, circa 1901, was one of the first Yiddish cookbooks published in the United States. Using her forty-five years of experience in European and American kitchens, Hinde Amchanitzki provided thousands of newly arrived Eastern European immigrants with an introduction to American cuisine, as well as recipes for traditional Jewish fare, in a language they could understand. In her introduction, the author (pictured on the cover) promises that using her recipes will prevent stomach aches and other food-related maladies in children.

Institution: U.S. Library of Congress, Hebraic Section.

American Jewish cookbooks capture the range of Jewish religious and cultural expression in the United States. Cookbooks are a form of literature that, uniquely, is largely written by and for women. Though many were published, many recipes remain parts of personal collections. In America, cookbooks produced by various Jewish groups reflected the diversity of American Jewry. As Eastern European immigrants arrived, commercial cookbooks began to embrace the unique culinary style because Jewish immigrants had become an important consumer market. Today’s American Jewish cookbooks address all elements of cuisine from a quick Passover mazzah brei to a fancy Thai celebration for twenty. These gourmet collections suggest the degree to which even the most observant of Jews are integrated into the social pastimes of the United States.

Introduction

When you are searching for instructions on how to prepare the perfect pickled tongue, for hints on setting a festive SabbathShabbat table, or a refresher course in the laws and lore of A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover, American Jewish cookbooks are an invaluable source of information on Jewish life. The first publicly available American Jewish cookbook was published in 1871. Esther Levy’s Jewish Cookery Book on Principles of Economy Adapted for Jewish Housekeepers with Medicinal Recipes and Other Valuable Information Relative to Housekeeping and Domestic Management was an attempt to touch on most aspects of Jewish home life. While few of the hundreds of Jewish cookbooks written since attempt the breadth of this first work, American Jewish cookbooks capture the range of Jewish religious and cultural expression.

Jewish cookbooks include recipes for all manner of Jewish and American dishes as well as exotic, gourmet, and ethnic fare. They are far more than technical manuals. For some women the kitchen and its responsibilities represent limitations placed on them in Jewish society; other women, however, use food and cookbooks as a means of expression. Written primarily by and for women, these books present their authors’ interpretations of and commitment to Judaism. The inclusion of traditional fare stresses attempts to maintain ties with the past, while recipes for smores and apple pie signify adoption of American culinary norms. Motherly voices retell the story of Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day.Hanukkah as an explanation of why we eat latkes. The frequent dedications to foremothers and/or offspring remind us that for many Jews food is an important means through which Judaism passes from generation to generation.

Defining American Jewish Cookbooks

American Jewish cookbooks include books dedicated to the preparation of fish as well as others that make suggestions on how to discipline your children. Indeed, no single criterion defines the American Jewish cookbook. Some can easily be identified as Jewish by the inclusion of the word “Jewish” in the title, such as Jewish Cookery Book or Jewish Cook Book. Others, such as Chinese Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).Kosher Cooking or The Yemenite Cookbook, can be identified as Jewish by the use of Hebrew or Jewish terms. Volumes put out by groups with a Jewish affiliation can be included in the category of American Jewish cookbooks even when they focus on topics not specifically Jewish, such as desserts. Jewish cookbooks often stress ritual or religious issues as well as recipes for traditional Jewish dishes. But Jewish contents such as a sweet raisin-studded noodle kugel do not mark the book as Jewish in all cases. A general book on holiday entertaining may suggest a Hanukkah menu between those for Christmas and Kwanzaa. Some Jewish foods, such as hallah—braided egg bread—that appeal to mainstream America palates appear regularly in general American collections. Particular attention to kashrut (Jewish dietary law) nonetheless remains a marker of uniquely Jewish cookbooks.

Kashrut

Not all American Jewish cookbooks engage kashrut, but those that do define the concept broadly. Some authors adhere to traditional Orthodox legal standards. Books in this category sometimes serve as detailed guides to keeping a kosher kitchen. For Lubavitch women, the way to cook a brisket cannot be separated from the choice of a proper kosher butcher; neither aspect of the preparation can be neglected. In addition to a large presentation of Jewish recipes, including eight variations of gefilte fish, the Lubavitch Women’s The Spice and Spirit of Kosher-Jewish Cooking describes aspects of religious law related to food, kitchen, and home.

Recipes for chicken in cream sauce, or other dishes that combine milk and meat, may not mean abandonment of kashrut but rather redefinition of the traditional term. Aunt Babette’s Cook Book, which first appeared in 1889, includes instructions for skinning a hare and steaming shellfish. Though paying great attention to these and other traditionally forbidden foods, the author made clear that she was reinterpreting, not renouncing, kashrut. In her mind, “Nothing is ‘Trefa’ that is healthy and clean.” Following this logic, she included recipes for ham but not for bacon. Other books’ authors show no ideological attachment to kashrut but maintain a cultural connection to the concept by not mixing meat and milk or by providing kosher alternatives to recipes that do mix milk and meat.

Personal Cookbooks

Everyone has an aunt or a friend who is always clipping and borrowing recipes. These collections, whether kept on scraps of paper in a box, on cards in a file, or in a book, are the essence of personal “cookbooks.” Whereas a cook may or may not use all or any of the recipes found in a purchased collection, personal cookbooks reflect most closely the foods prepared in Jewish homes. Many collections remain the property of one individual cook. The Gold family story, however, told when a personal cookbook was made publicly available, suggests how personal cookbooks can connect generations. When Evelyn Gold’s mother came to Canada from the Ukraine, she brought with her memories of food her mother had made and a good knowledge of Eastern European Jewish cooking. She applied this knowledge to the foods of Canada and through the years adapted numerous newspaper recipes to suit her taste. Later in life, she codified her eclectic collection of recipes and passed it on to her daughter. In 1994, Gold published this personal cookbook and dedicated it to the family’s next generation. Thus Jewish food tastes formed over time in the Ukraine and adapted to North America passed down through a family and to others in this personal cookbook.

Organizational Cookbooks

The organizational cookbook is an institution of American culture and Jewish life. Usually spurred by the desire and need to raise money, members of sisterhoods, women’s organizations or schools publish collections of recipes. Such projects allow broad membership participation as individuals contribute a favorite secret for preparing brownies or sweet and sour chicken. Additionally, such endeavors find a ready purchasing audience as members buy copies to see their name in print, send copies to relatives, or learn how to make the watercress soup Sylvia serves yearly at the sisterhood brunch.

The wide range of Jewish groups in North America is apparent in the diverse cookbooks these organizations produce. Some answer the specific needs of a particular community. The When You Live in Hawaii You Get Very Creative During Passover Cookbook highlights the community’s kitchen. This project not only brought members together in its production but also provides some practical suggestions for Passover, such as mazzah pie and hot-spicy zucchini latkes. A gay and lesbian congregation worked to have their cookbook reflect the diverse family constellations of its members, so, whereas most organizational cookbooks suggest quantities to feed four to eight, Out of Our Kitchen Closets provides meal plans for one, two, or many. Commonly, religious organizations concerned with observance include ritual information intended to guide members of the community.

Boston baked beans in collections from New England to burritos in those from the Southwest underscore the incorporation of local fare into America’s Jewish homes. Even traditional dishes come under regional influence as southern cooks trade the walnuts traditionally used by Jews for the more easily available pecan. Some home cooks feel comfortable combining the unique elements of Jewish and regional cuisine for creative recipes such as catfish mazzah-ball gumbo.

Each organizational cookbook is arranged according to its own principles. Sometimes editors focus on Jewish themes such as the holiday cycle, Passover foods or Shabbat cooking. Often food categories such as soups, meats or salads dominate, with either a special section for Jewish foods or Jewish dishes sprinkled throughout. Not all Jewish organizations, however, concentrate on Jewish dishes.

Commercial Cookbooks

While the category of cookbooks put together and published by organizations is by far the largest of the publicly aware available type of American Jewish cookbook, commercially published cookbooks are more widely available. The latter are expected to reach a broad readership, whereas the former primarily circulate locally.

Since 1871, and the very limited success of the first Jewish cookbook published in the United States, the popularity of commercial cookbooks has mounted steadily. Today, numerous American Jewish cookbooks appear from both Jewish and general commercial presses and are widely available. Recently, even that first volume has been reprinted.

The Nineteenth Century

Esther Levy saw her 1871 Jewish Cookery Book as a comprehensive guide for keeping a Jewish home. In the introduction, worried that young Jewish brides might not know how to instruct their maids in housekeeping matters, she included explanations of table setting and other points of etiquette. Working to counter the myth that “a repast, to be sumptuous, must unavoidably admit of forbidden food,” she provided instructions for mazzah charlotte and ochre gumbo as well as other recipes that blended contemporary tastes and Orthodox kashrut observance.

Levy’s book reflects the tastes and standards of her Philadelphia German Jewish community. German dishes such as pancake soup appear with both their original and translated names. Mazzah balls remain untranslated as Matzo Cleis. In contrast to the presence of German and English fare, Eastern European Jewish foods are noticeably absent. Levy’s omission of gefilte fish, a dish she likely did not know, led later cookbook authors to question the manual’s authenticity as a Jewish cookbook.

Writing under the pseudonym Aunt Babette, Bertha F. Kramer compiled in 1889 Aunt Babette’s Cook Book, Foreign and Domestic Resipst [sic] for the Household. Unlike Levy’s effort, this book went through multiple editions, several in the first year. Kramer claimed that her only intention in compiling this volume was to pass her secrets on to her daughters, but her attention to the extensive duties of a middle-class woman and the prominence of her German Jewish Reform publisher, Bloch Publishers, suggests a broader audience. Kramer made sure to provide instructions for all occasions from the grand wedding meal to the intimate “Koffee Klatch.” Housewives looking to be the perfect hostess could turn to Aunt Babette for directions on running a “Pink Tea” with pink foods, pink linens, and pink aprons for maids.

Eastern European Jews Arrive

Gefilte fish finally gained its central place in American Jewish cuisine with the mass immigration of Eastern European Jews (1880–1924). The variety of new American Jewish cookbooks of this period addressed this new group and its Old World foodways.

Some books benignly explained how to prepare the multitude of unfamiliar foods that mystified recent arrivals. (Such volumes explained that the inside, not the peel, of the yellow fruit called a banana was to be eaten.) Other books, often authored by progressive reformers, aimed to change how immigrants approached cooking and teach them how to cook American style. The Settlement Cook Book out of Milwaukee also explained household skills from washing dishes and feeding invalids to the intricacies of preparing a feast for forty. Its detailed menus and explicit instructions made it a basic handbook for cultivating American habits and nutritional standards.

Other commercial cookbooks embraced the culinary style of this new community. Slow-fermenting beet rosl and plump meat-filled kreplakh began to show up with regularity among the new recipe collections. Assuming a traditional and Yiddish-speaking audience, the new cookbooks often presumed Orthodox kashrut standards, and many were written in Yiddish.

Major American food manufacturers saw Jewish immigrants as an important consumer market. They not only advertised in Yiddish for American products but also provided recipes advising how to use their products in Jewish dishes. Crisco and Manischewitz were some of the many manufacturers that produced Yiddish/English cookbooks. These bilingual cookbooks were popular with general presses as well. A Yiddish-speaking cook could learn basic English vocabulary by looking across at the translation. Additionally, these books allowed a Yiddish-speaking mother and an English-speaking daughter to work from the same recipe side by side, thus facilitating the mother-daughter transmission of culinary knowledge.

The Science and Art of Jewish Cooking

Concerns about scientific approaches to nutrition, budgetary constraints and proper hostessing have merged with Jewish considerations in the pages of many American Jewish cookbooks. One early example, the Jewish Cook Book, published by Bloch Publishing Company, appeared first in 1918, later enjoying numerous editions and one major revision. Both the original author, Florence Kreisler Greenbaum, and Mildred Grosberg Bellin, author of the second version, were university-trained home economists. The two incarnations of this volume stress economy, nutrition and Jewish dietary restrictions. Speaking as authorities on scientific approaches to cooking, these women reassured their readers that a Jewish diet was compatible with contemporary concerns.

Starting with Esther Levy’s section on medicinal cures for everything from sore throats to diphtheria, American Jewish cookbooks have attended to health. By the 1920s, nutritional information was routinely being integrated into the body of menus and recipes. Today the complexity of dietary knowledge and health considerations can be seen in a variety of cookbooks that adapt Jewish dishes for diabetic, low-cholesterol or vegetarian diets.

Other authors feared that Jewish wives would be drawn away from kashrut and Jewish customs by the delights of Christmas trees, Easter baskets, and other elements of non-Jewish living. Several well-known and respected women joined in the effort to reassure Jewish homemakers that a Jewish life-style could properly express full womanhood. On behalf of the National Women’s League of Conservative Judaism, Betty Greenberg and Althea Silverman coauthored The Jewish Home Beautiful, the best-known book of this type. More than merely a recipe book, this volume includes a script for an elaborate musical and spoken pageant on Jewish living. Each section contains a photograph of a fancy table setting appropriate for marking the festivity of Jewish occasions. Even the The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur table, though lacking food, is beautifully laid out with silver candlesticks. This book was published multiple times and even served as a field guide to Jewish observance for American soldiers fighting in Europe during World War II.

If The Jewish Home Beautiful taught Jews how to bring American hostessing into their homes, The Molly Goldberg Jewish Cookbook brought Judaism into gentile homes. Gertrude Berg portrayed the beloved Molly Goldberg character, first on radio and then on television. Building on the popularity of the show, Berg (with Myra Waldo) wrote a Jewish cookbook that would appeal to the public at large. Published by the mainstream Doubleday Press, the book seamlessly weaves together Jewish and American holiday recipes, putting ethnic and national holidays on equal footing. Molly tells her readers, “Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purim and Lent [are] close together, and in my neighborhood you’d be surprised how the recipes change from hand to hand and back and forth.” Jews not only participate in America, but gentile Americans can also learn from Jews.

Ethnic and Gourmet Cooking

Into the 1960s, American Jewish cookbooks that wanted to include international fare chose dishes representative of the diversity of the world’s Jewish communities: chunky Hungarian goulash, spicy Yemenite, or the typical Israeli falafel. But in the latter part of that decade, virtually all Americans developed an awareness of ethnic cultures and began to integrate foods from around the world into their diets. Jewish cooks concerned with kashrut, and working to keep up with culinary trends, encouraged diversification of American Jewish cookbooks. Starting with Bob and Ruth Grossman’s series of Chinese, French, and Italian kosher cookbooks, many cookbooks attempted to merge the need of kosher cooks with the flavors and styles of ethnic food. Dishes such as mazzah lo mein highlight the uniqueness of the American Jewish kitchen.

This trend also encouraged the publication of cookbooks that reflect the diversity of the Jewish community in North America. Most American Jewish cookbooks represent the traditions of the Ashkenazi kitchen, but a growing number of Sephardi-oriented volumes, such as Copeland Marks’s Sephardic Cooking, offer insight into the traditions of American descendants of North African, Arab, and Spanish Jews. In recent years, American Jews have written cookbooks reflecting their families’ origins in countries such as Yemen, Italy and India.

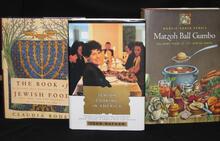

With the blossoming, in the 1970s, of cooking as a leisure activity in the United States, cookbook publication began to thrive, a trend that includes a growing number of Jewish cookbooks. Today’s American Jewish cookbooks address all elements of cuisine from a quick Passover mazzah brei to a fancy Thai celebration for twenty. These gourmet collections suggest the degree to which even the most observant of Jews are integrated into the social pastimes of the United States.

Most recently there has been a trend to publish cookbooks that capture the history of Jewish cuisine. One popular volume of this type is Jewish Cooking in America, in which Joan Nathan brings together heirloom recipes, anecdotes about Jewish food, and historic photographs—thus highlighting the centrality of food in Jewish American life.

Agabria, Hani, and Zion Levi. The Yemenite Cookbook (1988).

Berg, Gertrude, and Myra Waldo. The Molly Goldberg Jewish Cookbook. 2d ed. (1955).

Congregation Sha’ar Zahav. Out of Our Kitchen Closets: San Francisco Gay Jewish Cooking (1987).

Congregation Sof Ma’arav. The When You Live in Hawaii You Get Very Creative During Passover Cookbook (1989).

Gold, Evelyn. You Made My Day: Four Generations of Kosher Cooking (1994).

Goldberg, Betty S. Chinese Kosher Cooking. Middle Village (1989).

Grossman, Bob, and Ruth Grossman. The Chinese-Kosher Cookbook (1963), and The Italian-Kosher Cookbook (1964).

Kander, Mrs. Simon. The Settlement Cook Book (1934).

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. “The Kosher Gourmet in the Nineteenth-Century Kitchen: Three Jewish Cookbooks in Historical Perspective.” Journal of Gastronomy 2/4 (1986–1987): 51–87, and “Jewish Charity Cookbooks in the United States and Canada: A Bibliography of 201 Recent Publications.” In Jewish Folklore and Ethnology Review 9, no. 1 (1987): 13–18.

Levy, Esther. Jewish Cookery Book on Principles of Economy Adapted for Jewish Housekeepers with Medicinal Recipes and Other Valuable Information Relative to Housekeeping and Domestic Management (1971).

Lubavitch Women’s Organization Junior Division. The Spice and Spirit of Kosher-Jewish Cooking (1977).

Marks, Copeland. Sephardic Cooking: 600 Recipes Created in Exotic Sephardic Kitchens from Morocco to India (1992).

Nathan, Joan. Jewish Cooking in America (1994).

Shosteck, Patti. A Lexicon of Jewish Cooking: A Collection of Folklore, Foodlore, History, Customs and Recipes (1981).