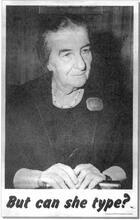

Geulah Cohen

Israeli politician Geulah Cohen, 1990. Photograph by Yaakov Saar. Courtesy of

Government Press Office (Israel), National Photo Collection, via Wikimedia Commons.

Born in Tel Aviv in 1925 to a family of Yemenite and Moroccan origins, Geulah Cohen was a prominent mainstay in Israeli politics. As a young woman, Cohen was involved in Revisionist Zionist organizations operating in British Mandatory Palestine, including Irgun Zvai Leumi (Etzel) and Lohamei Herut Yisrael (Lehi). Cohen’s ideological background in Revisionism characterized her hawkish political positions as a member of five Knessets from 1974 to 1992. During her career in the Knesset, Cohen was affiliated with the Likud party and later the Tehiya party, which she founded in 1979. Cohen received the Israel Prize for her contribution to Israeli society in 2003 before her death at age 93 in 2019. Her conviction inspired respect in both her political allies and rivals alike.

Early Life

Geulah Cohen was born in Tel Aviv in British Mandatory Palestine on December 25, 1925, to Yosef and Miriam Cohen. She was one of ten children in the family. Her father Yosef immigrated to Palestine from Yemen in 1905 during the period of the Second Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah from 1904 to 1914. In this time, a significant number of Yemenite Jews migrated to Palestine as a result of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire, increased ease of travel, and rumors of Messianic redemption. Her mother, Miriam, descended from a Moroccan Jewish family that arrived in Palestine in the late nineteenth century, coinciding with the First Aliyah from 1881 to 1903. This is unusual in relation to the broader context of the migration of North African Jews to Israel, the vast majority of which took place after the state of Israel’s founding in 1948 during a period now commonly called the Great Aliyah, roughly the late 1940s through the very early 1970s. Yosef was active in Zionist politics, and helped to found the Yemenite Association in Israel in 1923.

Cohen joined Betar, the youth branch of the Revisionist Zionist movement, in her early teens. Revisionist Zionism—whose founding is typically attributed to Ze’ev Jabotinsky in the early twentieth century—revolves around an amalgamation of sometimes seemingly opposed ideas, including a strong sense of secular Jewish national identity, veneration of liberalism and the individual, and the conviction that a Jewish state should encompass both banks of the Jordan River in accordance with the territorial demarcations of the ancient Kingdom of Israel and Kingdom of Judah. As a member of Betar, she developed the nationalistic, liberal, and territorially maximalist ideological positions that consistently informed her political career.

Membership in the Jewish Underground

In 1942, at age seventeen, Cohen joined the Revisionist Zionist paramilitary organization Irgun Zvai Leumi, commonly abbreviated to its Hebrew acronym, Etzel. One year later, in 1943, she left Etzel to join the more extreme Lohamei Herut Israel, frequently called Lehi by its Hebrew acronym, or, more pejoratively, the Stern Gang in an allusion to the organization’s penchant for violent tactics. Cohen cited her frustration with Etzel’s reservations about the deliberate use of violence against the British Empire as her primary motivation for switching organizations.

In the early to mid-1940s, the distinct paramilitary bodies of the various ideologically opposed strains of Zionism, such as the Labor Zionist Haganah, the Revisionist Zionist Etzel, and the more amorphous Lehi, clashed over their visions for a potential Jewish state and the means through which this state should be achieved. These conflicts manifested themselves in a number of ways, including aggressive propaganda campaigns, the Haganah’s efforts to get Etzel and Lehi members arrested en masse through collaborating with British police forces, systematic exclusion from housing and employment, and physical violence that resulted in injuries and even death. Because of her affiliation with Lehi, the Haganah, in conjuncture with the British Empire, orchestrated Cohen’s expulsion from the Levinsky Teacher’s Seminary where she studied in the mid-1940s.

Cohen was a leader of the Lehi’s media operations; she edited the youth newspaper HaZit HaNa’or (The Youth Front) and worked as one of the main hosts and broadcasters on the Lehi radio program Kol HaMahkteret (Voice of the Underground) under the nomme de guerre “Ilana.” In 1946, during a broadcast for Voice of the Underground, British police arrested Cohen for illegal possession of a wireless radio. For her crime, the British court sentenced her to nine years to be served at the British prison in Bethlehem. At the sentencing, members of Cohen’s family and dozens of fellow members of Etzel and Lehi erupted into a rendition of the song “HaTikvah” (The Hope), which became the national anthem of the state of Israel in 1948. This was a common act of resistance amongst members of Zionist paramilitaries sentenced to prison—and, on occasion, to death—especially amongst members of Etzel and Lehi.

Geulah Cohen, a leading radio broadcaster for the underground Zionist paramilitary organization Lohamei Herut Yisrael (Lehi), during a broadcast, 1948. Photograph by Hans Pinn. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Cohen made several escape attempts over the period of her trial and imprisonment. In 1947, after one year in prison in Bethlehem, Cohen escaped successfully with the help of local Arabs working with Lehi. She disguised herself in the clothing typical of Arab Muslim women, snuck out of the prison, and hid in the nearby village of Abu Gosh before fleeing the area. After adopting a disguise by dying her hair blond and sporting un-needed glasses, Cohen returned to hosting Voice of the Underground until the dissolution of the various Zionist paramilitaries and the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948.

Life After the Establishment of the State of Israel and Entry into Politics

Following the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, Cohen entered the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where she earned her MA in Jewish Studies, Philosophy, Literature and Bible Studies. Cohen continued her work in media and journalism and became a writer and member of the editorial staff of fellow Lehi member Israel Eldad’s political monthly, Sulam (Ladder), from 1948 to 1960. While working at Sulam, Cohen married Emmanuel Hanegbi, also a former member of Lehi. Their son Tzachi Hanegbi, born on February 26, 1957, is a long-time member of the Lit. "assembly." The 120-member parliament of the State of Israel.Knesset for Likud. Cohen left Sulam in 1960 and began to write for the popular Israeli daily newspaper Ma’ariv (“Evening”). She worked at Ma’ariv from 1961 to 1973, during which she contributed a regular column on society and politics and sat on the paper’s editorial board.

In the early 1970s, Cohen re-entered the world of political activism following a meeting with Chabad Lubavitcher Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson in New York City regarding the plight of Soviet Jews. In the 1960s through the 1980s, the Soviet Jewry Movement engaged Jewish organizations around the world, who drew attention to the Soviet Union’s systematic discrimination against Soviet Jewry and the repression of Soviet Jews’ human rights.

Career as a Member of the Knesset

Cohen’s immersion in the Soviet Jewry Movement spurred her to formally begin a career in Israeli politics. In 1972, she joined the political party Herut (“Freedom”), a Revisionist Zionist party headed by former Etzel leader and long-time ideological leader of the Israeli Right, Menachem Begin. With the election for the Eighth Knesset in 1973, Cohen became a member of Knesset (MK) for Begin’s Likud party, a consolidation of several right-wing parties that superseded Herut earlier that year. She spent the next four years as a member of the Knesset for the opposition.

In 1977, Likud won a majority of seats in the election for the Ninth Knesset, marking the first time in Israeli history that a right-wing political party formed a government. This watershed, colloquially referred to as HaMahapakh (“The Earthquake”), signaled the culmination of a number of transformations within Israeli society. These transformations include the collapse of Israeli socialism, the ideological ascension of the Israeli Right, and the assertion of Mizrahi Israelis’ political capital as a decisive factor in Israeli politics.

Cohen herself was an interesting representation of the significant connection between Mizrahi Israelis and the Israeli Right. While her young adulthood with the Lehi and her family’s arrival to Palestine in the late nineteenth to early twentieth century differentiated her from a majority of Mizrahi Israelis, they shared belief in essential Revisionist Zionist political values, including a broad and pluralist understanding of Jewish national identity, a warmth toward Jewish traditions, and support for a liberalized economy and political system. In fact, Likud’s 1977 victory is largely indebted to massive support from Mizrahi Israeli voters, who remain one of the Israeli Right’s core electorates to this day.

Still, while Cohen embodied the political leanings and affiliations of right-wing Mizrahi Israeli voters, she was one of just a handful of Mizrahi members of the Knesset in the mid-twentieth century. She was part of the still smaller number of female Mizrahi members of the Knesset, who, in 1977, included just Cohen herself and Labor party affiliate Shoshana Arbeli-Almozlino in roles of prominence.

As a member of the Knesset with Likud, Cohen served as the Chair of the Immigration and Absorption Committee. She remained affiliated with Likud until 1978, when Prime Minister Begin’s willingness to make territorial concessions in the Sinai as part of the 1978 Camp David Accords with Anwar Sadat’s Egypt violated Cohen’s uncompromising commitment to territorial maximalism. Cohen publicly castigated Begin in a session of the Knesset, decrying what she saw as a betrayal of Revisionist Zionism’s fundamental principles. The following year, in 1979, Cohen formed her own party, Tehiyah (“Revival”). Tehiyah’s membership was made up primarily of former Likud members and settler parties such as Gush Emunim that emerged out Israel’s territorial expansion into the West Bank and Gaza following the 1967 Six-Day War. For the duration of her political career, Cohen remained one of Israel’s most vocal proponents of territorial maximalism, opposing the Camp David Accords in 1978, the Oslo Accords in 1993 and 1995, and Israeli disengagement from the Gaza Strip in 2005.

In 1980, Cohen proposed the Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel, to the Knesset. The law proclaimed the city as the unified capital of the state of Israel and outlined the legal parameters of its status. The Ninth Knesset voted to ratify the law on July 30, 1980. One year later, in 1981, Cohen proposed the Golan Heights Law, which exerted similar jurisdiction in the Golan Heights near Israel’s border with Syria.

In spite of her personal differences with Begin, Cohen and her Tehiyah party joined the Likud government after its victory in the 1981 elections for the Tenth Knesset. Cohen went on to serve in the Eleventh Knesset and the Twelfth Knesset as well, serving in a total of five governments spanning from 1974 to 1992. She served as the Deputy Minister of Science and Technology from 1990 to 1991, during which she spearheaded the state’s efforts to facilitate Ethiopian Jews’ immigration to Israel.

Later Life and Legacy

Due to a lackluster showing for Tehiyah in the 1992 elections for the Thirteenth Knesset, Cohen did not earn a seat in the government. Still, she continued to actively participate in Israeli politics. She rejoined Likud and remained a strong voice on political and social issues at the end of the twentieth century and into the beginning of the twenty-first century. In 1993, Cohen briefly moved to the Kiryat Arba settlement near Hebron in the West Bank to demonstrate her solidarity with the settler movement after a period of heightened violence between Jewish settlers and Palestinians in the area.

In 2003, Cohen received the Israel Prize – the state’s highest cultural honor – in the category for lifetime achievement and exceptional contribution to the nation. In 2007, the Jerusalem Municipality named her Yakir Yerushalayim (“Worthy Citizen of Jerusalem”). On December 18, 2019, Cohen died at the age of 93. She is buried in the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.

Outspoken but effortlessly eloquent, fiery yet debonair, Cohen’s devotion to her beliefs demanded respect from across the spectrum of Israeli society. She drew admirers from Mizrahim and Ashkenazim, religious and secular, and Right and Left alike who recognized in her tirelessness a deep and spirited love for Israel and the Jewish people.

Selected Publications by Geulah Cohen

Cohen, Geulah. Sipur shel Lohemet (“Story of a Fighter”). Tel Aviv: Karn, 1961.

Cohen, Geulah. HaTapuz Sheba’ar Vehetzit Levavot (“The Orange that Burned and Ignited Hearts”). Jerusalem: Aryeh Ben-Elizer, 1979.

Cohen, Geulah. Mifgash Histori (“Historic Meeting”). Tel Aviv: Avraham Stern, 1986.

Cohen, Geulah. Ein Li Koah Lehiyot Ayefa (“I Don’t Have Strength to be Tired”). Jerusalem: Re’uven Mas, 2008.

Aderet, Ofer and Jonathan Lis. “Former Lawmaker Geulah Cohen, the ‘First Lady of the Right,’ Dies at 94.” Ha’aretz. December 19, 2020. Accessed June 13, 2020. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-former-lawmaker-geulah-coh….

Atkins, Stephen E. Encyclopedia of Modern Worldwide Extremists and Extremist Groups. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004.

Quinn, Sally. “The Fighter in the Promised Land, Geula Cohen and the New Zionism.” The Washington Post. October 11, 1978. Accessed June 13, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1978/10/11/fighter-in-….

Shilon, Avi. Menachem Begin: A Life. Translated by Danielle Zillerberg and Yoram Sharett. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

The State of Israel. Knesset. “Knesset Members, Geulah Cohen.” Accessed June 13, 2020. https://www.knesset.gov.il/mk/eng/mk_eng.asp?mk_individual_id_t=444.