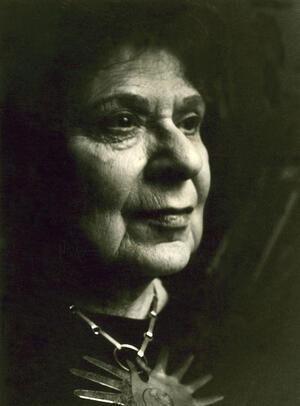

Ruth Leah Bunzel

Anthropologist Ruth Leah Bunzel did groundbreaking work on the relationship of artists to their work and on alcoholism in Guatemala and Mexico. Bunzel was the first to analyze how artists felt about traditional styles and the creative process instead of just discussing the objects they created. She later wrote about Zuni religion, poetry, and social organization. Bunzel went on to compare alcoholism in two villages in Mexico and Guatemala, looking at psychological, economic, and political reasons for alcoholism, like the haciendas that benefited from keeping Indians subjugated and in debt through alcoholism. Beyond her fieldwork, Bunzel worked for the Office of War Information in New York and London and taught at Columbia University. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, she also worked to stop nuclear proliferation.

Ruth Leah Bunzel began her career as anthropologist Franz Boas’s secretary and became an accomplished anthropologist herself. She broke new ground in her research on the artist and the creative process among the Zuni, her pioneering work on the Mayas in Guatemala, and her comparative study of alcoholism in two villages in Guatemala and Mexico.

Early life: childhood, education, career beginnings

Ruth Leah (Bernheim) Bunzel, the youngest of four children, was born in New York in 1898, and lived on the Upper East Side of Manhattan with her parents, Jonas and Hattie Bernheim, of German and Czech heritage. Her father died when Ruth was ten years old, and she was raised by her mother, who had inherited money from her family’s Cuban tobacco-importing business. Ruth’s mother raised the children in a Jewish household that was largely acculturated to American ways. The family spoke English at home, but Ruth’s mother encouraged Ruth to study German at Barnard College. Ruth, however, changed her major because of the political atmosphere surrounding World War I and received a B.A. in European history from Barnard in 1918.

Talking about the choices that bright young people confronted in the 1920s, Bunzel wrote that some went to Paris seeking freedom, some aligned with radical workers and sold the Daily Worker on street corners, and others turned to anthropology to “find some answers to the ambiguities and contradictions of our age and the general enigma of human life.” She saw anthropology as a means to understand not only others but also ourselves.

Having taken a course with Boas in college, Bunzel succeeded Esther Goldfrank as his secretary and editorial assistant at Columbia University in 1922. In 1924, she accompanied anthropologist Ruth Benedict to western New Mexico and east-central Arizona to study the Zuni people and followed Boas’s suggestion to give up typing and begin her own research on a topic that interested him, the artist’s relationship to work. Critical of ethnographers who often ignored women as subjects in their fieldwork, Bunzel felt that “society consisted of more than old men with long memories.” She was drawn to the Zuni because women were the potters and had considerable societal power.

Career advances: a PhD, published work, and gaining respect

Bunzel began graduate study in anthropology at Columbia University. In 1929, she received her Ph.D. with the publication of a landmark book on the artistic process, The Pueblo Potter. Rather than focusing on the objects of art, Bunzel was the first anthropologist to analyze artists’ feelings, their relationship to their work, and the process of creativity. To understand how artists work within the confines of traditional styles, Bunzel apprenticed herself to Zuni potters, and among them she became a respected, skilled potter.

Visiting the Zunis intermittently between 1924 and 1929, Bunzel was a sensitive fieldworker, respecting local factionalism and esoteric ceremonies. Bunzel’s focus on the individual and the degree of aesthetic freedom an individual had in a given culture influenced her writing on Zuni kachina (ancestral spirit) cults and mythology, ceremonialism and religion, and poetry. A prolific scholar, she also contributed an understanding of Zuni cosmology and social organization by producing important work on Zuni values, language, culture, and personality. Deeply influenced by Boas and Ruth Benedict, Bunzel’s work, in turn, provided much of the material for Benedict’s synthesis of Zuni in Patterns of Culture. In addition to the Zuni, Bunzel wrote about the Hopi, Acoma, San Ildefonso, and San Felipe Pueblo Indians of the southwestern United States.

Bunzel was one of the first American anthropologists to work in Guatemala, and she published a monograph on the Chichicastenango community in highland Guatemala in 1952. Reflecting both her interest in culture and personality studies and the neo-Freudian influence of psychoanalyst Karen Horney, she also wrote a comparative study on alcoholism in Chamula in Chiapas, Mexico, and in Chichicastenango. Her research, supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship (1930–1932), looked at psychological factors that led to different patterns of drinking in two communities. She also focused on the role alcohol played in the Indians’ subjugation and how haciendas profited by keeping Indians in debt. Her study on alcoholism was the first anthropological writing on this subject.

Outside the field: Europe, teaching, and anti-proliferation

Bunzel went to Spain to perfect her Spanish and to gain background information for her southwestern Indian studies and was there when the Spanish Revolution broke out. During World War II, from 1942 to 1945, Bunzel worked for the Office of War Information in New York and London. From 1946 to 1951, Bunzel participated in the Research in Contemporary Cultures Project, directed by Ruth Benedict, which specialized in Chinese cultures. She had participated in seminars led by Abraham Kardiner (1936 and 1937) held at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute and Columbia University, which influenced her postwar national character study.

Bunzel taught sporadically at Columbia University throughout the 1930s, but she became an adjunct professor in 1954 until her retirement in 1972. She then spent two years as a visiting professor at Bennington College. Bunzel earned a modest living teaching and felt she had never obtained full-time work because she was a woman. Others have attributed her marginal position, in part, to hostility between Boas and Ralph Linton, who became chair of the anthropology department at Columbia.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, she worked with other colleagues against the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Bunzel was a private person with several lifelong relationships, mostly with female colleagues. She lived much of her life on Perry Street in Greenwich Village, never leaving New York and Columbia University for long periods, except to do field research. She died in 1990 of cardiac arrest. Her detailed fieldwork and writing are known for their great sensitivity and quality and remain an enduring legacy of her anthropological accomplishment.

Selected works by Ruth Leah Bunzel

“Art.” In General Anthropology, edited by Franz Boas (1938): 535–588.

“Chamula and Chichicastenango: A Reexamination.” In Cross Cultural Approaches to the Study of Alcohol, edited by Michael W. Everett, Jack O. Waddell, and Dwight B. Heath (1976).

Chichicastenango, a Guatemalan Village (1952).

“The Economic Organization of Primitive Peoples.” In General Anthropology, edited by Franz Boas (1938): 327–408.

“Further Notes on San Felipe.” Journal of American Folklore 41 (1928) 592.

The Golden Age of American Anthropology, with Margaret Mead (1960).

“Introduction to Zuni Ceremonialism.” Bureau of American Ethnology BAE Annual Report 47: (1932) 467–554.

“The Nature of Katcinas.” BAE Annual Report 47 (1932): 837–1006. Reprinted in Reader in Comparative Religion, edited by A.W. Lessa and Evon Vogt (1958): 401–404.

“Notes on the Katcina Cult in San Felipe.” Journal of American Folklore 41 (1928): 290–292.

The Pueblo Potter: A Study of Creative Imagination in Primitive Art (1929).

“Psychology of the Pueblo Potter.” In Primitive Heritage, edited by Margaret Mead and Nicolas Calas (1953): 266–275.

“The Role of Alcoholism in Two Central American Cultures.” Psychiatry 3 (1940): 361–387.

“The Self-effacing Zuni of New Mexico.” In The Americas on the Eve of Discovery, edited by Harold Driver (1964): 80–92.

“Zuni.” In Handbook of American Indian Languages. Part 3, edited by Franz Boas (1933): 385–515.

Zuni Texts (1933).

Zuni Ceremonialism: Three Studies. Edited by Nancy J. Parezo (1992).

“Zuni Origin Myths.” BAE Annual Report 47 (1932): 545–609.

“Zuni Ritual Poetry.” BAE Annual Report 47 (1932): 611–835. Reprinted as Zuni Ceremonialism: Three Studies (1992).

Babcock, Barbara A., and Nancy J. Parezo. “Ruth Bunzel, 1898—.” Daughters of the Desert: Women Anthropologists and the Native American Southwest, 1880–1980. An Illustrated Catalogue (1988): 38–43.

Bunzel, Ruth Leah. File. Wenner-Gren Foundation, New York City.

Caffrey, Margaret M. Ruth Benedict: Stranger in this Land (1989).

EJ; Fawcett, David M., and Teri McLuhan. “Ruth Leah Bunzel.” In Women Anthropologists: A Biographical Dictionary, edited by Ute Gacs, et al. (1988): 29–36.

Hardin, Margaret A. “Zuni Potters and The Pueblo Potter: The Contributions of Ruth Bunzel.” In Hidden Scholars: Women Anthropologists and the Native American Southwest, edited by Nancy J. Parezo (1993): 259–270.

Howard, Jane. Margaret Mead: A Life (1984).

Murphy, Robert F. “Ruth Leah Bunzel.” Anthropology Newsletter 31, no. 3 (March 1970): 5.

Parezo, Nancy J. Introduction to Zuni Ceremonialism: Three Studies, by Ruth L. Bunzel (1992): vii–xxxix.

Woodbury, Nathalie F.S. “Bunzel, Ruth Leah.” In International Dictionary of Anthropologists, edited by Christopher Winters (1991).