Aline Bernstein

Aline Bernstein was one of the first theatrical designers in New York to make sets and costumes entirely from scratch and craft moving sets. Bernstein met the owners of the Neighborhood Playhouse while volunteering at the Henry Street Settlement House and began designing sets for them. She saw the theater’s small budget as a creative challenge, and the set she made received praise. She began designing for other theaters and built a formidable reputation. In 1928, Bernstein became the designer for the Civic Repertory Company. In later life, she designed sets for the Theatre Guild and various independent producers, winning numerous awards for her work, including a Tony for costume design for Regina in 1949. She later founded the Costume Museum and began writing fiction.

In the world of theater, Aline Bernstein is remembered as one of the most important designers of the first half of the twentieth century. In the world of literature, she is remembered for loving, not wisely but too well, one of the great writers of her time, the young Thomas Wolfe. She was a woman of many and remarkable talents who lived a strikingly full life and made an indelible impression personally and professionally.

Early Life and Family

Joseph Frankau was a respected actor in the New York theater when he married Rebecca Goldsmith, the gentle daughter of a wealthy lawyer. Their first child, Aline, was born on December 22, 1880, in the house Joseph and Rebecca had been given by her father on their marriage. Not long after, the elder Goldsmith died, leaving little behind but debts. Frankau, more devoted to the theater than to financial security, was happy to move with his family to a boarding house run by his sister-in-law Mamie.

There, surrounded by actors and laughter and the marvelous food cooked by her aunt, young Aline grew up. Her father woke her in the middle of the night to recite the classics to her. She chanted “Tiger, tiger, burning bright” on her way to school to enliven the walk. She was a very happy child. At the age of eleven, however, she lost her mother to cancer. A few years later, with her father’s help, she began studying to be an artist. After classes at the New York School of Applied Design, she went to concerts and theater parties with her father, where she participated in conversations about music and art and life.

Then, when Aline was sixteen, her father died of a heart attack. For the next few years, she and her younger sister, Ethel, were shunted around from relative to relative. Sometimes they managed to stay together; sometimes they were parted. They had no stable home, but Aline found a sense of belonging when she walked the streets of the Lower East Side, among the sights and sounds of her childhood, of her people. “My Jewishness runs through me like a strain of gold,” she would say later in life.

Early Career and Neighborhood Playhouse

After graduating from the School of Applied Design, Bernstein began studies with portraitist Robert Henri. Through him, she was again surrounded by people and conversations and ideas. She met anarchist Emma Goldman and artists such as Man Ray. She also met a young stockbroker named Theodore Bernstein, whom she married in November of 1902. Ethel moved in with the couple, and the three of them were never again apart.

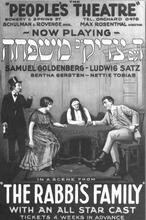

In 1911, the two sisters began to volunteer their time at the Henry Street Settlement House, founded by Lillian Wald. There Bernstein met Alice and Irene Lewisohn, who were developing a theater at Henry Street. Before long, she was the main designer at the Neighborhood Playhouse. In her biography of Bernstein, Carole Klein writes, “Already the Playhouse was being called, admiringly, ‘a woman’s theater,’ and newspapers reporting their progress announced that: ‘No man has anything whatsoever to do with it except by invitation.’”

The Neighborhood Playhouse was the first New York theater to design and make all of its own costumes, props, and scenery. Indeed, critic John Gassner has said that the profession of “scene designer” originated at this small, innovative community theater which produced the early works of such writers as Clifford Odets, Elmer Rice, and even Eugene O’Neill. Bernstein continued to work there even after she began to design for the commercial theater and did some of her best work under the Playhouse’s budget constraints. Critic Brooks Atkinson called her design for The Dybbuk “a Rembrandt canvas.”

During this time, Bernstein also gave birth to two children, Theodore and Elda. Her marriage was a happy one, and she found great satisfaction in the role of wife and mother, as she did in her increasingly successful and demanding career. When she was in her early forties, she realized that the deafness which was part of her family’s genetic legacy had become quite serious. Her doctor told her that her impairment would become more severe with time. She learned to read lips and carried on.

Career Successes and Love Affair

In the 1923–1924 season, Bernstein had two stunning successes. Her strikingly original design for The Little Clay Cart at the Playhouse was based on Rajput painting. She also assisted Norman Bel Geddes in the creation of hundreds of costumes for Max Reinhardt’s production of The Miracle on Broadway. The two consolidated her reputation as a designer. An enormously vital and energetic woman, she began to design show after show, raiding museums for warrants of authenticity and traveling to Europe to gather materials.

It was on her return from one of the European journeys that forty-five-year-old Bernstein met and fell in love with twenty-five-year-old Thomas Wolfe. Her passion was thoroughly reciprocated, and a new stage in her life began.

For the next five years, Bernstein and Wolfe waged a war. It was fought on many fronts, not the least of which was between themselves. They also fought Wolfe’s inner demons, which were many. The pain of a conflict-filled childhood fueled his writing, but it often prevented it as well. Bernstein nurtured and nourished him while he struggled to create his monumental first novel, Look Homeward, Angel.

On another front, Aline fought to keep her passion for Wolfe from destroying her marriage and family. It was a difficult battle, but she was helped by her husband’s sensitivity and understanding and by the loving equity she had accumulated in twenty-three years of dedication to him and their children.

In this context, the battles of her professional life often seemed smaller than they were. There was the struggle, for example, that theatrical designers were carrying on to unionize. They were eventually allowed to join the Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators and Paper Hangers Local Number 829, of the American Federation of Labor—all except Bernstein. Local 829 did not have any women in its membership and was not interested in changing that situation. Bernstein eventually won that battle and became good friends with many of the brothers.

In 1928, Eva Le Gallienne approached Bernstein about becoming resident designer for her new theater, the Civic Repertory Company. Bernstein threw herself into the project, enabling the cash-poor group to function as a true repertory company by designing a unit set with movable parts that could be adapted easily to a variety of plays.

Later Life and Legacy

Wolfe’s breakup with Bernstein in 1930 left both of them shattered. She went into a deep depression that threatened her family life in a way that the passion of her affair had never done. He went into an emotional tailspin from which he never completely recovered. They continued a rocky friendship for years, in spite of a latent vein of antisemitism in Wolfe that he would mine at moments when he most wanted to hurt Bernstein. He wrote about her and her family in two novels and several short stories. When he died at the age of thirty-eight, the last words he said were a cry for Aline. She later arranged for his letters to her to be included in a collection of his papers at Harvard University with the understanding that a sizable donation be made to the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies.

With time, Bernstein recovered from her depression. She began designing for the Theatre Guild and a number of independent producers. Her sets and costumes for plays by Lillian Hellman, Elmer Rice, James Thurber. and others won her innumerable awards. She also founded the Costume Museum, which later became part of the Museum of Modern Art. She began writing and received critical acclaim for her work. May Sarton wrote of her novel The Journey Down, “I was up all night reading your book. It is a beautiful piece of work, with the intensity, texture and peculiar sustained excitement of a poem.”

Aline Bernstein won a Tony Award for her costume design for the opera Regina in 1949, when she was seventy. It was one of four shows she did that season. In 1953, she did her last design work, the costumes for the Off-Broadway production of The World of Sholom Aleichem. She died in New York on September 7, 1955.

Aline Bernstein Designs, 1922-1952. Archival Collection, New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts. http://archives.nypl.org/the/22019

Houghton, Norris. “The Designer Sets the Stage.” Theatre Arts (February 1937).

Klein, Carole. Aline. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Monteverdi, Anna. Scenografe. Storia della scenografia femminile dal Novecento a oggi. Audino, 2021.

NAW.

Obituary. NYTimes, September 7, 1955.

Stutman, Suzanne, ed. My Other Loneliness: Letters of Thomas Wolfe and Aline Berinstein. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.