Blanche Bendahan

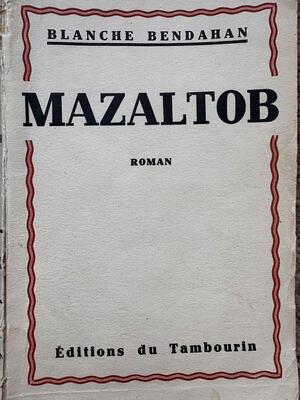

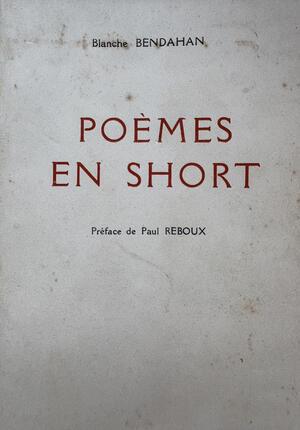

Blanche Bendahan had a successful literary career as a poet, essayist, and novelist, earning numerous literary prizes for her work. Acclaimed for her lectures in France and throughout North Africa on topics as diverse as Sepharadism, feminism, and humor, she was also known for her novel Mazaltob (1930), a romantic tale of hopeless love set in the judería (Jewish quarter) of Tetouan, a small city in northern Morocco whose inhabitants encounter the lures of westernization. The novel garnered both commercial and critical acclaim, including being honored by the prestigious Académie Française, which awarded it one of its annual prizes in 1931. Bendahan was also celebrated as a poet and a humorist. She earned unique distinction in 1949 for her Poèmes en short (1948), a whimsical collection of poems.

Blanche Bendahan had a successful literary career as a poet, essayist, and novelist, earning numerous literary prizes for her work. Acclaimed for her lectures in France and throughout North Africa on topics as diverse as Sepharadism, feminism, and humor, she was also known for her novel Mazaltob (1930), a romantic tale of hopeless love set in the judería (Jewish quarter) of Tetouan, a small city in northern Morocco whose inhabitants encounter the lures of westernization.

Family and Early Life

Blanche Jeanne Benoliel had an unconventional and peripatetic childhood. She was born on November 26, 1893, in Oran, a port city in northwest Algeria. Ruled by France since 1848, as was the rest of Algeria, Oran was home to a varied and colorful population, as Arabs mingled with Frenchmen, Italians, and Spaniards from the nearby Iberian Peninsula. Sounds of French, Spanish, Italian, Judeo-Spanish, and Arabic filled its streets. Religious diversity prevailed as well. Muslims and Christians interacted both with local Jews, who spoke Judeo-Arabic, and those who came from Livorno, Italy, and Tetouan, Morocco.

Bendahan was born a French citizen thanks to the Crémieux Decree, which granted most Algerian Jews French citizenship in 1870. She never knew her mother, Maria Fernandez, a Catholic from Málaga, Spain, who died in childbirth at the age of nineteen. A few months later, Blanche, having been born out of wedlock, was adopted by her biological father, Hayo (Alfred) Benoliel, who was born in Oran to a Jewish family from Tetouan. Like most Tetouani Jews, the Benoliels cherished both their vivid Judeo-Spanish language known as Haketia and their Sephardi cuisine, customs, songs, and traditions, many of which Bendahan enthusiastically embraced.

Blanche’s family relocated frequently: first to Nice, when Blanche was only a baby, later to Paris, Toulouse, and Grenoble, eventually returning to Oran when she was fourteen. By then, Hayo had divorced Marie Ginoux, a Catholic Frenchwoman he had married three years after Blanche's birth. Little is known about Marie Hortense Ginoux. Perhaps she was a teacher in Blanche’s school. Her marriage certificate, however, lists no profession, a fact not uncommon even when women worked up to the time of their marriage. That she came from a respected family is apparent from her father’s profession as a rentier and that he had been awarded the Légion d’honneur. Ginoux’s presence loomed large in Bendahan's life—so much so that Bendahan touchingly dedicated Mazaltob, "a Jewish novel," to this Catholic stepmother. Lengthy discussions on the convergences between Christianity and Judaism also find their way into the novel.

Writing Career

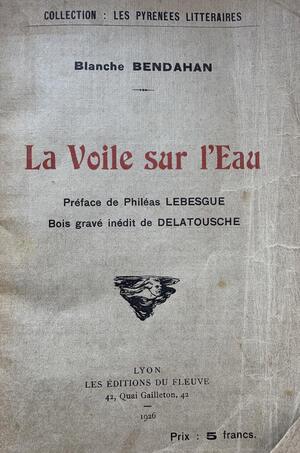

Subsequent to the Dreyfus Affair in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century France, Algeria—including Oran, despite its cosmopolitan culture—was mired in antisemitism, frequently fanned by French pieds-noirs (pieds-noirs, or “black feet,” is the name given to the European inhabitants of Algeria who were born in the country). Nevertheless, Blanche blossomed as poet, novelist, and journalist. Her first poetry collection, La voile sur l’eau (The Drifting Sailboat), was published in 1926. Her interests were wide-ranging; she wrote about factories in Algeria, advances in modern medicine, and the beautiful vistas of Oran, as well as lectured on Islam, North Africa, and humor at the Sorbonne and the Emagine Theatre. She was one of only two women ever to receive a prize from the renowned Académie de l'Humour (established in 1923) and was the recipient of various other prestigious awards, including Officier de l’Instruction Publique, Commandeur du Mérite et du Dévouement Français, and Commandeur des Arts, Sciences et Lettres. At 26, already renowned for articles and essays in Oran's journals, she married Gaston (Yahia) Bendahan, a Tetouani Jew who, like her father, was a colonial goods merchant. They appear to have had no children.

Bendahan was also a political activist, working to bring Muslims, Christians, and Jews together as a member of the Union of Monotheistic Believers established in 1932. In 1933 she became a founder and member of the executive committee of Oran’s chapter of the Ligue française pour le droit des femmes (LFDF), a progressive suffragist movement with a feminist agenda. One of the chapter’s foremost missions was “to organize literary conferences with the aim of advancing women’s rights.”

Mazaltob was published in Paris in 1930 on the centenary of the French invasion of Algeria and republished in Oran in 1958 in the last years of French rule. Journals and newspapers from both the right and the left, Algeria and the metropole, lauded Mazaltob’s realism, picturesque descriptions, and refutation of “false” observations. In 1931 France’s prestigious Académie Française awarded Mazaltob one of its annual prizes. The only Jewish laureate among 53 (eight were women), Blanche Bendahan stood alone as well in having written on a Jewish theme.

Bendahan weaves a poignant tale in which tradition and emancipation exist in stark tension. Mazaltob is a young Jewish woman from Tetouan’s judería who falls in love with Jean, her French childhood companion and a free thinker. At the age of sixteen, however, she is betrothed by her family to José Jalfon, a man she does not love and who subsequently forsakes her for a dissolute life in Buenos Aires.

In the clash between "tradition" and "modernity," France is portrayed favorably as an emancipating force brought by the Alliance Israélite Universelle, an international Jewish organization founded in Paris in 1860. Among its mandates was the “regeneration” of Jews from North Africa, the Middle East, and the Ottoman Empire through the establishment of a network of schools stretching from Tetouan to Tehran. In the novel, Mazaltob attends Tetouan’s Alliance school for girls, eagerly imbibing its French culture and language.

While "modernity" in Mazaltob is embodied by France, tradition is featured in the “antiquated” ways of Tetouan, where the Jewish population fiercely held on to its Sephardi traditions. Bendahan illustrates these traditions in her novel, from birth ceremonies to wedding customs and death rituals, in such detail that the Jerusalem-born journalist and ethnographer Avraham Elmaleh pronounced her work “a classic of Sepharadism.” For just as the novel starkly exposed the conflict between an old world and a new one, so too it delicately blurred the line between them. In Mazaltob, Bendahan may have derided the dangers of living entrenched in the past, but she also wrote eloquently and proudly of family, community, and time-honored traditions, presciently anticipating not only the benefits but also the perils awaiting North African Jewish communities.

At first glance, Bendahan's poetry differs markedly from the style of her best-selling novel Mazaltob. Her most original collection of poems, the prize-winning 1948 Poèmes en short, features pieces severed from the author's North African context. Rather, they are steeped in the philosophical vein of seventeenth-century French moralists, but with a modern twist. "Please read these poems," the noted French critic Paul Reboux advised, "you will understand why I enjoyed them so much. They are noble and classic yet bursting with life. They are whimsical yet realistic, delicate yet ferocious, filled with irony yet also faith” (Poèmes en short preface).

Nevertheless, a profound unity runs through Bendahan’s two major works. Poèmes en short presents brief vignettes unmasking the foibles and follies of the human condition. “Janus,” the opening piece, enunciates Bendahan's poetics, highlighting her wish to be "contemporary." For Bendahan was foremost a modernist who favored concise sentences, opted for a mix of registers, and melded formal and informal language. Under the guise of an ethnographic narrative, Mazaltob featured a similar endeavor. With its blending of high and low voices, its rich borrowings from different literary traditions, and its brief, vivacious scene sketches, her novel is as stylistically bold as her poetry. Bendahan’s feminism is another vital thread throughout: women make frequent appearances in her work, usually as victims of the prevailing patriarchy.

Bendahan bridged disparate worlds: she was French and Algerian, Oranese and Tetouani, Jewish and Christian, a novelist and a poet. She spoke fondly of her Sephardi Jewishness but overlooked it in her poetry. She left Oran when Algeria gained its independence in 1962 and Jews departed en masse. She spent the last years of her life in Nice, a city she knew well from childhood, where she continued to write about Algeria. Until her death on July 23, 1975, she never ceased to long for her beloved Oran.

Selected Works by Blanche Bendahan:

La voile sur l’eau, Préface de Philéas Lebesgue. Lyon: éditions du Fleuve, 1926.

Mazaltob. Paris: Editions du Tambourin, 1930.

Mazaltob, a novel. English edition. Edited and translated by Yaëlle Azagury and Frances Malino. Waltham: Brandeis University Press, 2024.

Poèmes en short, préface de Paul Reboux. Paris: Editions René Lacoste, 1948.

“Visages de Tetouan.” Les Cahiers de l’Alliance Israélite Universelle (Paix et Droit), no. 93 (November 1955).

Sous les soleils qui ne brilleront plus. Nice: L’Amitié par le livre, 1970.

Benkada, Saddek. “Blanche Bendahan (1893-1975), être écrivain, femme et juive à Oran dans l’entre-deux-guerres (1919-1939).” Société d’Histoire des Juifs de Tunisie, Colloque “Les Juifs du Maghreb de l’époque coloniale à nos jours, histoire, mémoire et écriture du passé.” Paris, Sorbonne, November 3-6, 2008.

Dugas, Guy. La littérature judéo-maghrébine d’expression française. Paris: Editions de L’Harmattan, 1991.

Elmaleh, Abraham. “Ha-soferet Ha-meshoreret Blanche Bendahan Ve-yetziroteha Ha-sifrutiot.” Les cahiers de l’Alliance Israélite Universelle 4-6, vol 10 (May 1961): 93-96.

Leibovici, Sarah. Chronique des juifs de Tétouan (1860-1896). Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose, 1984.

Miller, Susan Gilson. “Gender and the Poetics and Emancipation: The Alliance Israélite Universelle in Northern Morocco (1890-1912).” In Franco-Arab Encounters, edited by L. Carl Brown and Matthew Gordon. Beirut: American University of Beirut Press, 1996.