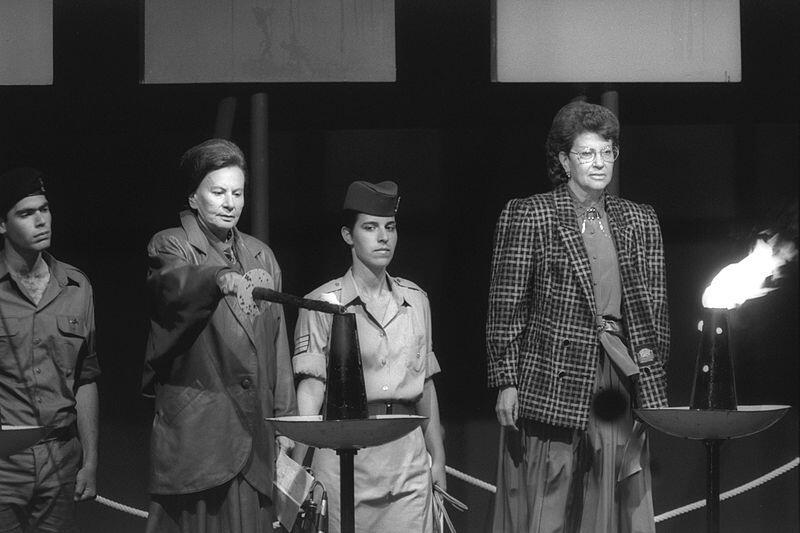

Miriam Ben-Porat

Although Miriam Ben-Porat is perhaps best known as the first woman to be appointed an Israeli Supreme Court Justice, she also held many positions throughout her life from state comptroller to professor and author. After starting her law career at the Ministry of Justice, Ben-Porat became the State Attorney before then moving to the District Court. She eventually became president and served on the District Court for eighteen years. She was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1976, where she made rulings characterized by both legal and non-legal elements and grounded in the principles of equality and good faith. After retiring from the Supreme Court, she became the first female State Comptroller, where she shifted the focus onto preventing improper governmental behavior before it occurred.

Early Life and Education

The first woman to be appointed a Justice in Israel’s Supreme Court, Miriam Ben-Porat was born on April 26, 1918, in Vitebsk (Belorussia). Her father, Elieser Sheinson (d. 1941), a merchant and manufacturer, was born in Aniksht, Lithuania. His homemaker wife, Haya (née Ric, d. 1941), was also born in Lithuania. The couple, who moved to Kovno (Kaunas) soon after Miriam’s birth, had three daughters and four sons. Of these, Pinhas, together with his parents, was murdered by the Germans in Lithuania in 1941. Shimon managed to escape to Russia, Rachel to South Africa, and Binyamin, Reuven and Bella, like Miriam, reached Palestine.

Miriam grew up in Kovno, where she completed high school, and in 1936 she immigrated to Palestine. She studied law in Jerusalem from 1937 to 1942 and by February 1945 had completed her internship and received her lawyer’s license. In 1946 she married Joseph Ben-Porat (Rubinstein), a manufacturer, who was born in Poland. A daughter, Ronit, was born in November 1955.

After two years at the Ministry of Justice (1948–1950), Ben-Porat was promoted to be deputy to the State Attorney, a position in which she served from 1949 to 1958. On one occasion, when she represented the prosecution, her argument—which appeared as though it were part of the defense—resulted in a majority ruling by the Supreme Court that in criminal cases irresistible impulse, as a result of mental illness, is to be regarded as a defense.

Career as a Judge

In 1958 Ben-Porat was appointed a judge in the Jerusalem District Court, of which she became vice president in May 1975 and president in December of that year. Early on in this position, she ruled that the elections to the Jerusalem Municipal Council were invalid, since fifty ballot envelopes had not been stamped according to law and therefore had not been counted. It emerged that had the General Zionist Party received an additional five votes, its candidate would have won a seat, in place of a Mapai candidate. Judge Ben-Porat maintained that the real issue was not the number of invalid votes that determined whether or not the elections were valid, but rather the question as to whether these votes, had they been counted, could have changed the outcome of the elections. Aware of the serious implications of cancelling the election results entirely, Ben-Porat ruled, basing herself on evidence presented to the court, that the failure to stamp these envelopes stemmed from an error in good faith, and she therefore proposed that the legislature should validate the votes. As a result, the Lit. "assembly." The 120-member parliament of the State of Israel.Knesset passed an ad-hoc law, the unstamped envelopes were opened, and it emerged that none of them contained a vote for the General Zionists. The cancellation of the elections was thus averted.

In November 1976 Ben-Porat was appointed an acting justice in the Supreme Court and in March 1977 a permanent justice. From November 1983 until her retirement in April 1988 she was deputy president of the Supreme Court.

Rulings

Ben-Porat’s rulings are characterized by a remarkable compound of various elements, both legal and non-legal: a wide and profound range of legal knowledge, coupled with logic, common sense, flexibility and a foundation in basic rights such as the principles of equality and good faith. She laid down innovative and precedent-setting rulings on a wide range of issues. In a 1969 case of disputed inheritance, she ruled in favor of the deceased’s divorced wife, who had been specifically designated a beneficiary, even though in the will she was referred to as his wife. In 1977, in a minority opinion in a case of The Israel Electric Corporation vs. Haaretz newspaper, she ruled that the principle of freedom of expression does not take precedence over a person’s good name. In a further hearing, her opinion was accepted by a majority of four to one. In the ensuing years, there have been various further rulings in similar cases. The court appears to be concerned with protecting the individual’s good name when he/she is slandered by unproven statements, even when these constitute criticism regarding public affairs.

In 1979 Ben-Porat ruled that, when there is a plurality legal system, the court must be flexible and choose the most appropriate and relevant of the options. She made a significant contribution to contract law in 1984, when she ruled that from the time of the two sides’ signing on an agreement, the assumption is that they agreed on all its provisions; thus any divergence from the contract’s provisions would undermine legal certainty as to the parties’ intention.

On Criminal Law

A 1986 ruling established the right of Israel’s president to pardon a criminal even before he had been convicted or even tried, on condition that the offender admitted his guilt. However, the president should exert this right only rarely and only when its application was truly warranted.

In 1980 the court ruled unanimously that a Jew who forces his wife to have intercourse with him is acting unlawfully. Two of the judges on the panel based themselves on Jewish law (din), but Justice Ben-Porat—in an individual ruling—referred to her judgment as covering all such perpetrators, arguing that the term “unlawfully” (not according to din) was meaningless in other articles of the law. The deputy president of the court, Haim Cohn, accepted her argument in dismissing the application for a further hearing. He dismissed the other grounds (Jewish personal status law).

On Government

In 1987, Ben-Porat ruled that the oath of loyalty taken by a member of Knesset must be in accordance with the terminology of the law, i.e. “I undertake,” with no addition. This referred to MK Meir Kahane’s version, which obscured the oath’s intention.

In the sphere of public administration, aware of the inherent lack of symmetry between the authorities and the individual citizen, she was punctilious in applying severe standards to governmental authorities in order to deter and penalize governmental bad faith or abuse of power. Ben-Porat did not hesitate to intervene in cases where the executive branch improperly applied legislative directives. In 1978 she restricted the authority of the military in the occupied territories, holding that eviction or expropriation of property was permissible only for purposes of self-defense or essential security measures.

In 1979 Ben-Porat contributed to legal certainty on issues of planning and construction, when she ruled that from the moment that a national council used its legal authority to transfer an issue to a sub-committee which it had established, the decisions taken by the latter are to be regarded as decisions of the national council. In 1983, she ruled that the principle of equality applied to the conditions in government tenders.

State Comptroller

Upon her retirement from the Supreme Court in 1988, Ben-Porat was appointed State Comptroller and Ombudsman for Public Complaints—a position in which she was again the first woman—and she filled this role in a dynamic and innovative manner. She significantly changed the office’s modus operandi in that she replaced scrutiny of government action after the event with preemptive reports and measures intended to prevent improper governmental behavior before it occurred. One example of such action was her report during the Gulf war (1991) that the masks did not fit the faces of many inhabitants. As a result, they were replaced by new ones.

Furthermore, instead of contenting herself with the previously customary annual reports, Ben-Porat published a series of special reports dealing with burning issues on the public agenda. One of her most revolutionary acts was her appeal to the media to harness themselves to the battle against corruption in high places. To this end she granted courageous and critical interviews on matters of governmental misdemeanor, unlike her predecessors, who rarely allowed themselves to be interviewed. The transparency in the work of her office and her use of the media as a tool to promote that work greatly increased public awareness of the war against corruption and, in effect, recruited the general public to that battle.

Ben-Porat brought about a change in the public agenda with the publication of the State Comptroller’s Annual Report in 1991, in which she courageously exposed social and immoral phenomena that had spread throughout the government. She cited flaws and corruption in government operations, such as the transfer by political parties of special funds in unprecedented amounts to fictitious institutions, with no government supervision whatsoever. She also inveighed against political appointments, citing cases of totally unqualified individuals who had been given government positions solely because of their connection to people in power. This was a battle she continued even after her retirement from the position of State Comptroller. As Comptroller, she also pointed out the state’s discriminatory behavior against Arab citizens and called for actively involving them in Israel’s social and national fabric.

After completing two terms as State Comptroller, Ben-Porat retired from the office in 1998, generally acknowledged as having been its most active occupant and as the one who had most significantly transformed its standards.

Teaching Work and Legacy

From 1964 until her appointment to the Supreme Court, Ben-Porat was a lecturer in the Law School of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, attaining the rank of associate professor, but she retired from teaching in order to devote herself solely to her position as justice of the Supreme Court and, later on, as State Comptroller. In 1999 she resumed teaching, both at the Israeli branch of Manchester University and at the Interdisciplinary Center in Herzliyyah. She was the author of a variety of articles published in legal journals, of a book on state comptrol (An Interpretation of the Basic Law: State Comptroller, 1998 [2005]), and a commentary on the law of assignment. She remained active in public causes, such as the battle against the destruction of antiquities on the Temple Mount.

In 1990 Ben-Porat was awarded the Judge Zeltner Prize and in 1991 she received the Israel Prize, the country’s most distinguished award, for her special contribution to society and the state. She was also the recipient of honorary degrees from the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York (1997), the University of Pennsylvania (1993), the Hebrew Union College, Jerusalem (1999) and the Weizmann Institute of Science (2004).

In 2010, she published an autobiography entitled Through the Robe (מבעד לגלימה).

Miriam Ben-Porat died at her home in Jerusalem on July 26, 2012. She was 94.

Kershner, Isabel. "Miriam Ben-Porat, Israeli Judge and Civic Watchdog, Dies at 94." The New York Times 26 July 2012: N.p. The New York Times. Web.