Sarah Bas Tovim

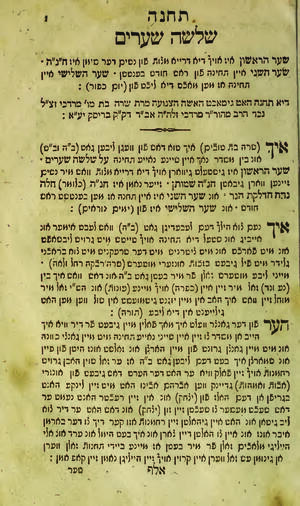

Text of Tkhine shloyshe sheorim (The Tkhine of Three Gates) by Sarah Bas Tovim, early 18th century. From a prayerbook published in Vilna in 1850. Courtesy of Aharon Varady and the Open Siddur Project.

Sarah bas Tovim was an elusive figure, and the difficulty of documenting her life has led to doubts about her very existence. She is the author, or more precisely the composer, of two works published in the eighteenth century: Tkhine shaar ha-yikhed al oylemes (The Tkhine of the Gate of Unification concerning the Aeons) and Tkhine shloyshe sheorim (The Tkhine of Three Gates). By the time she wrote her second book, Sarah had developed a distinctive and powerful literary voice, including autobiographical material and making use of rhyme, internal rhyme, and assonance to enhance her literary style. The figure of Sarah bas Tovim continued to live in the imagination of the people and in the literary imagination of Yiddish authors.

Background

Sarah bas Tovim (Sore bas toyvim), daughter of Mordecai (or daughter of Isaac or Jacob, as sometimes listed on the title pages of various editions of her works), of Satanov in Podolia, in present-day Ukraine, great-granddaughter of Rabbi Mordecai of Brisk (on this, all editions agree), became the emblematic tkhine [q.v.] author, and one of her works, Shloyshe sheorim, perhaps the most beloved of all tkhines. An elusive figure, in the course of time she took on legendary proportions; indeed, some have insisted that she never existed. The fact that the name of her father (although not her great-grandfather) changes from edition to edition of her work, and the unusual circumstance that no edition mentions a husband, make it difficult to document her life. In fact, the skepticism about Sarah’s existence is rooted in the older scholarly view that no tkhines were written by women authors, and that all of them were maskilic fabrications. Since a number of women authors have now been historically authenticated, there seems no reason to doubt that there was a woman, probably known as Sore bas toyvim who composed most or all of the two eighteenth-century texts attributed to her. Rather unusually for the genre of tkhines, her works contain a strong autobiographical element: She refers to herself as “I, the renowned woman Sore bas toyvim, of distinguished ancestry” and tells the story of her fall from a wealthy youth to an old age of poverty and wandering, a fall she attributes to the sin of talking in synagogue.

Tkhines

Sarah is the author, or more precisely the composer, of two works published in the eighteenth century, Tkhine shaar ha-yikhed al oylemes (The Tkhine of the Gate of Unification concerning the Aeons) and Tkhine shloyshe sheorim (The Tkhine of Three Gates). Like other tkhine authors, Sarah often includes portions of earlier works and is indeed quite forthright about this. She states that her works were “taken out of holy books,” thus claiming more prestige for them than if they were merely her own creations, and that she “put them into Yiddish,” thus implying a Hebrew source. Yet she also says that they “came out of” her, thus taking overall responsibility for the texts. Another level of bibliographical complexity is the liberty printers and publishers took with Sarah’s works, as they did with other tkhines, changing, rearranging, and editing them as they saw fit in subsequent editions. Because eighteenth-century tkhines published in Eastern Europe rarely contain a notice of place or date of publication, it is very difficult to establish the bibliographic history of Sarah’s works. However, her use of excerpts from other sources allows us to date them to the middle of the eighteenth century.

Tkhine shaar ha-yikhed al oylemes (a title with kabbalistic overtones) contains one long tkhine to be recited Mondays and Thursdays (considered minor penitential days) and on fast days. This portion of the text includes, among other things, a Yiddish paraphrase of Ecclesiastes 12:1–7, and a confession of sins that expands and explicates the standard alphabetic formula. Although this text contains many Hebrew phrases and verses, it is not a Yiddish translation or paraphrase of any of the usual penitential prayers said on these days. The work concludes with a tkhine to be said before making memorial candles for The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur, a theme which recurs in her second work. This portion of the text incorporates material from Nakhlas Tsvi (“Inheritance of Tsvi”), a Yiddish paraphrase of portions of the Zohar by Tsvi Hirsh Hotsh, published in Amsterdam in 1711 and in Zolkiew in 1750.

By far the more popular and famous work by Sarah is her second book, the Shloyshe sheorim. This work contains tkhines for three of the most popular occasions for which tkhines were published in Eastern Europe: the three women’s mitsvot (the first “gate”), the Days of Awe (the second “gate”), and the New Moon (the third “gate”). By the time she wrote this work, Sarah had developed a distinctive and powerful literary voice, including autobiographical material and making use of rhyme, internal rhyme and assonance to enhance her literary style.

The most distinctive material is found in the second and third “gates.” Sarah’s tkhine for the ritual of kneytlakh leygn (“laying wicks”) to make candles for Yom Kippur is a liturgy for a centuries-old women’s folk ritual, widely attested in The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic, literary and ethnographic sources. Briefly, women went to the cemetery and measured its circumference (or individual graves) with candle-wicking, later rubbing the wicks with wax to make candles, one for the living members of the family, and one for the dead, going back to Adam and Eve and the patriarchs and matriarchs. These were burned in the synagogue or at home on Yom Kippur. Tkhines were recited at all stages of this ritual. Sarah’s powerful tkhine for making the candles calls on the forefathers and foremothers of the Jewish people to aid their descendants with a healthy and prosperous New Year and also to bring the Messiah, the end of death and the resurrection of the dead.

The tkhine for the Sabbath before the New Moon contains a great variety, one might say a hodge-podge, of material to be recited at the Blessing of the New Moon, much of it drawn from kabbalistic sources. It begins with an appeal to Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses and the “King Messiah” to arise and redeem Israel; this prayer derives, through an intermediate text in Yiddish, from Sefer Hemdat Yamim (Book of the Days of Delight), a widely read kabbalistic guide to the Jewish festival cycle, which originated in Sabbatian circles. After an expanded Yiddish paraphrase of the Hebrew prayer announcing the New Month, the text continues with a description of the women’s paradise, which is drawn from the Zohar (III 167b), again, through an intermediate Yiddish source. This section concludes with a number of other prayers, asking for forgiveness of sins, health and prosperity, and the messianic redemption. Indeed, a distinctive characteristic of Sarah’s tkhines is the way she combines eschatological and domestic concerns. This, and the literary power of her writing, helps account for her continuing popularity.

The figure of Sarah bas Tovim continued to live in the imagination of the people and in the literary imagination of Yiddish authors. Shalom Jacob Abramovitsh (Mendele Mokher-Sforim) mentions Sarah’s tkhines in his fictional autobiography, Shloyme Reb Khayyims (Ba-yamim ha-hem, Of Bygone Days). One of the most powerful scenes in the book is a description of women making memorial candles before Yom Kippur, reciting a version of Sarah’s tkhine for kneytlakh leygn. Sarah also became the subject of a short story, “Der ziveg; oder, Sore bas toyvim,” (“The Match; or, Sarah bas Tovim”) by I. L. Peretz, in which she appears as a sort of fairy godmother, helping those who faithfully recite her tkhines. Because she was so well-known, nineteenth-century female/sing.: Member of the Haskalah movement.maskilim who wrote tkhines to sell often attached her name to their own creations.

Niger, Shmuel. “Di yidishe literatur un di lezerin.” In Bleter geshikhte fun der yidisher literatur. New York: 1959 (first published 1912), 35–107, especially 83–85.

Bas Tovim, Sarah. “Tkhine of Three Gates.” In The Merit of Our Mothers: A Bilingual Anthology of Jewish Women’s Prayers, compiled and introduced by Tracy Guren Klirs, translated by T. G. Klirs et al. (Yiddish and English). Cincinnati: 1992, 12–45.

Weissler, Chava. Voices of the Matriarchs. Boston: 1998, 31–33, 76–85, 126–146.

Zinberg, Israel. History of Jewish Literature, vol. 7: Old Yiddish Literature from its Origins to the Haskalah Period, trans. Bernard Martin. New York: 1975, 252–254.