Liliane Atlan

In post-World War II France, the French Jewish writer, Liliane Atlan (née Cohen) wrote plays, poetry, and narratives in an innovative, contemporary French style interwoven with liturgical patterns and syntax reminiscent of liturgical Jewish texts, lexical traces of Hebrew, Ladino, and Yiddish, as well as Jewish mystical imagery. Liliane and her immediate family survived the Nazi German occupation in hiding in rural France, while her maternal grandmother and uncles were deported and died in Auschwitz. In addition to a prolific body of poetry and narrative, Atlan wrote three major works on the theme of the Holocaust: a play, Monsieur Fugue ou le mal de terre (Mister Fugue or Earth Sicknessm 1967); an autobiographical narrative, Les passants (The Passers-by, 1989), and a mixed-genre ritual performance accompanied by music, Un opéra pour Terezin (An Opera for Terezin, 1997).

Introduction

Liliane Atlan was a post-World War II French Jewish writer whose plays, poetry and narratives display innovative forms at the limit of written and oral literature. Her writing combines poetic rhythms with visual effects, dramatic ritual with musical accompaniment, and narrative prose with spoken inflections.

Atlan’s consciousness of her Jewish identity—like that of many assimilated French citizens d’origine juive (of Jewish origin)—was profoundly impacted by the Nazi German Occupation of France in 1940, the French collaborationist regime of Vichy, and the Holocaust or Shoah, the attempted extermination of European Jews. The crucial question underlying Atlan’s artistic production, in her own words, is “comment intégrer, sans en mourir, dans notre conscience, l’expérience radicale qu’a été Auschwitz” (“how do we integrate, without dying in the attempt, within our consciousness, the shattering experience of Auschwitz”; Letter to Judith Morganroth Schneider, December 4, 1989). Drawing on personal memories of the Occupation, testimonials of Holocaust survivors, investigation of historical archives, and intensive study of sacred and secular Jewish texts, Atlan thematically explores the meaning of post-Holocaust Jewish identity in her literary works. Implicitly, she manifests her Jewish consciousness by interweaving, in her contemporary French style, formal elements found in traditional Jewish writing, including liturgical rhythms and syntax, linguistic traces of Hebrew, Ladino, and Yiddish, and a lexicon rich in Jewish mystical imagery.

Early Years: In Hiding and Emerging

Liliane Atlan, née Cohen, was born in Montpellier in the south of France on January 4, 1932. Her mother was born in Marseille, France, in 1905, while her father, born in 1907, emigrated with his parents from Salonica, Greece, at the age of seven. Elie Cohen, Liliane’s father, was a businessman, and her mother, Marguerite Cohen, née Beressi, took care of their home and five daughters. Having left high school at the age of sixteen, Elie Cohen taught himself law and literature, reading the works of the great French poets, Hugo, Verlaine, and Valéry. Marguerite Cohen completed high school and, at the start of World War II, ran the family business, while her husband served in the French army. Liliane’s older sister, Rachel, was born in 1929, her younger sister Josette in 1937, Danièle in 1942, and Denise in 1944. Rachel, Josette, and Denise became jewelers and managed a factory. Danièle took care of her family and did not work outside the home. The Cohens led a comfortable, middle-class life until Liliane’s seventh year, when the family went into hiding in the Auvergne to escape French fascist and Nazi German persecution. Excluded from school, Liliane and her sister Rachel created plays in the attic where they were hidden. This marked the beginning of Liliane’s vocation as a tragic playwright, as she later noted: “I was the scenery, the actors, the author, and everything in that world within me cried out, gesticulated, died” (Knapp, “Collective Creation,” 9). Liliane’s nuclear family survived the Holocaust, but her maternal grandmother and uncles were deported and died in Auschwitz.

When the Occupation ended, Liliane returned to school at the Lycée des Jeunes Filles of Montpellier, later attending the Lycée des Jeunes Filles of Marseille. Her father became active in Jewish relief efforts and sheltered survivors of the camps. The Cohen family adopted a nineteen-year-old Holocaust survivor, Bernard Khul, who was uncommunicative upon his release from Auschwitz but eventually recounted the atrocities committed in the camp to Liliane, his fourteen-year-old adoptive sister.

During this postwar period, Liliane became anorexic and was sent for treatment to a clinic in Switzerland. Later, she went to Paris to study at the Gilbert Bloch School of Orsay, a Jewish school founded by Robert Gamzon (1905–1961) with the goal of helping European Jewish youth recover from the post-traumatic shock of the Shoah. At Orsay, Liliane and her companions spent sleepless nights passionately studying the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud, and the mystical Zohar as well as the A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrashic commentaries. From 1952 to 1953 she earned a degree in philosophy at the Sorbonne under the direction of the prominent French scholar, Gaston Bachelard. Bachelard’s books on poetry and water, air, earth, and fire convinced his student that true poetic images are associated with the four elements of nature.

In 1952 Liliane married Henri Atlan (b. 1931), a fellow student at Orsay, who became an internationally recognized scientist and philosopher. Their daughter Miri was born in 1953 and their son Michaël in 1956, both in Paris.

Poet and Playwright

Atlan’s first and most frequently staged play, Monsieur Fugue ou le mal de terre (Mister Fugue, or Earth Sickness, 1967) was inspired by an actual incident of the Shoah. Confined to the Warsaw ghetto, Janusz Korczak, a Polish Jewish writer and physician, directed an orphanage for Jewish children. In 1942, Korczak accompanied 200 orphans deported to Treblinka, telling them stories on the train to the gas chambers.

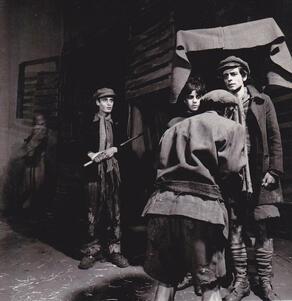

In Atlan’s play, a mix of dark comedy and tragedy, Nazi troops capture four Jewish children as they emerge from hiding in the sewers. In the back of a truck, on the way to their execution, one of the soldiers crouches beside the children and helps them dramatize, from birth to old age, the lives they will never live. Monsieur Fugue opened at the Théâtre de Saint Etienne in Saint Etienne in 1967, under the direction of the avant-garde theater director Roland Monod, and was revived in 1968 in Paris at the Théâtre National de Paris, also under Monod’s direction. Following these productions, Atlan and her family spent two years (1968–1970) living near San Francisco, while teaching French to American college students. The Atlans then moved to Israel for three years (1970-1973). There the playwright organized an Israeli/Palestinian theater group that performed in Hebrew and Arabic, using theater as a means of bridging cultures. This early theatrical experimentation with intercultural conflict resolution prepared the ground for Atlan’s play, Les musiciens, les émigrants (The Musicians, the Emigrants, 1976), which would premiere at the Théâtre du Versant in Biarritz in 1984. Monsieur Fugue, translated into Hebrew by Haim Gouri, was performed in Israel in Tel Aviv in 1972, under the direction of David Bergman. From 1973 to 1974 Atlan again resided in the United States, this time appointed writer in residence in the Iowa Writing Program of the University of Iowa.

In the wake of May 1968 and a new wave of French feminism, Atlan experienced an emotional and intellectual crisis, as did many other French intellectuals. Within her life and writing she debated her personal religious beliefs and practices, re-examined her role as mother, wife, and woman, questioned the efficacy of political activism, doubted the significance of book learning, and explored the allures of eroticism. Her self-interrogation inspired the plays Les Messies ou le mal de terre (The Messiahs or Earth Sickness, 1969) and La petite voiture de flammes et de voix (The Little Carriage of Flames and Voices, 1971), theatrical creations whose postmodernist aesthetic represented shattered truths and fragmented identities. La petite voiture premiered at the Avignon Festival in 1971, receiving enthusiastic reviews. At this time, Atlan began writing Le rêve des animaux rongeurs (The Gnawing Rodent’s Dream) (1985), an autobiographical narrative. Le rêve traces the sadness of the author’s marital dissolution and the exhilaration of experimentation with intercultural affective relationships. From 1977 to 1978, Atlan directed theatrical improvisations used as therapy for drug addicts in treatment at the Centre Médical Marmottan. A compilation of these videotexts, entitled Même les oiseaux ne peuvent pas toujours planer (Even Birds Can’t Stay Forever High), and Le rêve des animaux rongeurs, were broadcast on France Culture, a French national radio station. Published in 1985, Le rêve was later staged at Biarritz (1992) and at Annecy (1994).

Innovative Holocaust Writing

During the 1980s and 1990s Atlan returned to the theme of the Shoah with the publication of Les passants (The Passersby, 1989) and “Un Opéra pour Terezin” (“An Opera for Terezin,” 1997). Les passants, another autobiographical narrative, tells the story of an adolescent who questions her adoptive brother regarding his experiences in Auschwitz. As the protagonist listens to his account of horrors, she gradually begins to starve herself. At the conclusion of Les passants, the young girl leaves the Swiss sanatorium that successfully treated her anorexia, declaring that she now understands her purpose in life. She will no longer be called “Non” (“No”), for her true name is “Je ne suis pas née pour moi-même” (“I was not born for myself”) (Les passants 89). This literary epiphany emphasizes Atlan’s own assumption of the traditional role of Jewish intellectual as keeper of memory and teller of the story of the most recent attempt to destroy the Jewish people. The playwright transformed Les passants into a theatrical work entitled Je m’appelle Non (My Name is No, 1998), which was broadcast by France Culture in 1994 and performed on stage at the Avignon Festival in 2003.

“Un Opéra pour Terezin” (“An Opera for Terezin,” 1997) was Atlan’s last major recreation of her traumatic encounters with the Holocaust. This theatrical ritual reenacts the experience of European Jewish writers, artists, actors, and musicians and the cruelty of their German Nazi persecutors who confined them to a hybrid ghetto/camp in the small Czechoslovakian town of Terezin (renamed Theresienstadt by the occupying Germans). The Nazis represented the camp as a model community for retired Jews in the German propaganda film The Führer Gives the Jews a Town. In fact, shortly after the film’s completion, its s Jewish director and cast were executed (Moraly 170). In Atlan’s “Un Opéra,” the horror is real: musicians virtually play quartets without instruments, singers on the verge of collapse from starvation perform operatic arias, and members of the chorus deported to the death camps are regularly replaced by new arrivals to Terezin. The work’s structure loosely follows the ritual of the Passover Seder; its four divisions, accompanied with music, correspond to the four cups of wine imbibed during the Passover commemoration. “Un Opéra” initiates Atlan’s aesthetic of “la Rencontre en Étoile” (“the star-shaped Meeting”), in which participants around the world simultaneously commemorate the tragedy of the Shoah and rekindle the spirit of resistance emanating from artistic works that survived the annihilation of their creators (Atlan, “Opéra,” 3). In Atlan’s theatrical ritual, “electronic images are projected on video screens directly and instantaneously in different parts of the theater—and in other theaters in various areas of the globe where the same ritual is being enacted—thus abolishing linear time” (Knapp, “Review of ‘Un opéra,’” 257). Paradoxically, in her earliest plays, Atlan had specified the use of visionary effects that stage directors found impossible to actualize in their productions, but by the time she created “Un Opéra” the avant-garde effects she had envisioned so many years earlier had become technologically feasible.

Scenes from “Un Opéra” were first presented in 1985 at the University of Iowa during Atlan’s second appointment as writer-in-residence in the International Writing Program. In 1989 Radio-France and the Festival of Montpellier broadcast the work in its entirety in an all-night, outdoor performance from the Cloître des Ursulines. In 1994 the Théâtre du Versant performed an abridged version of “Un Opéra” at the Avignon Festival. A trilingual internet reading of a new abridged version was performed by actors in Israel, France, and the United States on January 27, 2021 (www.liliane.atlan). The work has also been performed in abridged versions at the University of Glasgow, the Freie Universität of Berlin, the University of Paris III, and the University of Tel Aviv.

Liliane Atlan was awarded prestigious international literary prizes during her lifetime: the Habimah and the Mordechai Anielewicz prizes in Israel in 1972 for Monsieur Fugue; the WIZO prize for Les passants in 1989; the Radio S.A.C.D. prize in 1999; the Jacob Buchman Foundation Memory of the Shoah prize for the ensemble of her works in 1999. Atlan’s plays have been translated and published in English, German, Hebrew, Italian, and Japanese. They have been performed repeatedly in France and also in Austria, Canada, Holland, Israel, Poland, Switzerland, and the United States.

Liliane Atlan spent most of her life in Paris. She died in Israel on February 15, 2011, survived by her two children, Miri Keren and Michaël Atlan, and her six grandchildren.

Selected Works

Plays

Monsieur Fugue ou le Mal de terre. Paris: Seuil, 1967.

Les messies. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2002. First published Paris: Seuil, 1969.

La petite voiture de flammes et de voix. Paris: Seuil, 1971.

Les musiciens, les émigrants. Paris : L’avant-scène: 1993. First published Paris: P.J. Oswald, 1976.

Leçons de bonheur. Paris: Editions Crater, 1997. First published Paris: Théâtre Ouvert, 1982.

“Un Opéra pour Terezin.” L’avant-scène: théâtre, no. 1007/1008 (April 1/15, 1997: 1-155.

Les mers rouges: un conte à plusieurs voix. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1999.

Je m’appelle Non: une piece de théâtre pour personne adulte et des adolescents. Paris: L’Ecole des Loisirs, 1998.

La vieille ville. Afterward by Daniel Cohen. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007.

Les portes. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007.

La bête aux cheveux blancs. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007.

Petit lexique rudimentaire et provisoire des maladies nouvelles. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007.

Les ânes porteurs de livres. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007.

Poetry

Lapsus. Paris: Seuil, 1971.

L’Amour élémentaire: poème, monologue. Toulouse: L’Ether Vague, 1985.

Bonheur, mais sur quel ton le dire. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1996.

Peuples d’argile, forêts d’étoiles. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2000.

Prose

Le rêve des animaux rongeurs. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1999. First published : Toulouse: L’Ether Vague, 1985.

Les passants. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1998. First published: Paris : Payot, 1988.

Quelques pages arrachées au grand livre des rêves. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1999.

Les passants: suivi de, Corridor paradis concert brisé: un récit en deux temps. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1998.

Petites bibles pour mauvais temps. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2001.

Même les oiseaux ne peuvent pas toujours planer. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007.

Translations into English

“Mister Fugue or Earth Sick,” “The Messiahs,” “The Carriage of Flames and Voices.” Theatre Pieces: An Anthology. Edited and translated by Marguerite Feitlowitz. Introduction by Bettina Knapp. Greenwood, FL: Penkevill, 1985.

“Mister Fugue or Earth Sick.” Translated by Marguerite Feitlowitz. Plays of the Holocaust: An International Anthology. Edited with an introduction by Elinor Fuchs. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 1987.

The Passersby. Translated with a preface by Rochelle Owens. New York: Holt, 1993.

The Red Seas: A Tale for Several Voices, followed by the original play, Les mers rouges: Un conte à plusieurs voix. Translated by Léonard Rosmarin. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007.

Small Bibles for Bad Times: Selected Poems and Prose of Liliane Atlan. Translated by Marguerite Feitlowitz. Simsbury, CT: Mandel Vilar Press; Takoma Park, MD: Dryad Press, 2021.

“Story”. Translated by Judith Morganroth Schneider. Centerpoint 3 (1978): 93-94.

Interviews

Atlan, Liliane. Liliane Atlan: Conversations. Interview by Daniel Cohen. September 26, 2006. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2006. DVD, 26:00.

Atlan, Liliane. “Collective Creation From Paris to Jerusalem: An Interview With Liliane Atlan.” Interview by Bettina L. Knapp. Theater (Fall-Winter 1981).

Atlan, Liliane. “Interview with Liliane Atlan.” Interviews with Contemporary Women Playwrights. Compiled by Kathleen Betsko and Rachel Koenig. New York: Beech Tree Books, 1987.

Gaudet, Jeannette. “Liliane Atlan: Les Passants.” Writing Otherwise: Atlan, Duras, Giraudon, Redonnet, and Wittig. By Jeannette Gaudet. Amsterdam: Rodopi: 1999.

Keren, Miri, and Michaël Atlan. “Liliane Atlan.” Created 2015. https://www.lilianeatlan.com

Knapp, Bettina L. “Cosmic Theatre: The Little Chariot of Flames and Voices.” Modern Drama 17 (1974) : 225-234.

Knapp, Bettina L. “Introduction.” Theatre Pieces: An Anthology by Liliane Atlan. Translated by Marguerite Feitlowitz. Greenwood, FL: Penkevill, 1985.

Knapp, Bettina L. Liliane Atlan. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1988.

Knapp, Bettina L. “Mal-être. L’Oeuvre scénique et poétique de Liliane Atlan.” Les Nouveaux Cahiers (Summer 1995).

Knapp, Bettina L. “Atlan, Liliane. Un Opéra pour Terezin.” Review of “Un Opéra pour Terezin,” by Liliane Atlan. The French Review, 72, no. 2 (December 1998): 356-357.

Moraly, Yehuda. “Liliane Atlan's Un Opéra pour Terezin.” Staging the Holocaust: The Shoah in Drama and Performance. Edited by Claude Schumacher. Cambridge: CUP, 1998: 169-183.

Oore, Irène. “Portes et louanges: Les Passants de Liliane Atlan.” LittéRéalité, 4, no. 2 (Automne/Fall 1992): 29-37.

Rosmarin, Léonard. Liliane Atlan ou la quête de la forme divine. Toronto: Editions du Gref, 2004 and Paris: L’Harmattan, 2004.

Schneider, Judith Morganroth. “Liliane Atlan: Jewish Difference in Postmodern French Writing.” Symposium 43 (Winter 1989-1990): 274-283.

Schneider, Judith Morganroth. “Liliane Atlan.” Daughters of Sarah: Anthology of Jewish Women Writing in French. Edited by Eva Martin Sartori and Madeleine Cottenet-Hage. Teaneck, NJ: Holmes & Meier, 2006: 123-126.