Polly Adler

Notorious for her connections with gangsters at the height of Prohibition, Polly Adler fought to become “the best goddam madam in all America.” Separated from her family by the Great War as a teenager, Adler did factory work until her friendship with a bootlegger created a very different opportunity for making money: using his apartment as a base for herself and women she hired to entertain his gangster friends. Adler went on to open a series of increasingly fancy brothels, culminating in a resort in Saratoga Springs, New York. Investigated and arrested often, the unflappable madam kept her doors open until 1943 when she retired to California to earn her high school diploma, start a college degree, and write a memoir.

Article

Polly Adler, owner of a notorious New York City bordello, had a clear goal: to become “the best goddam madam in all America.” Her earlier plan had been to attend the gymnasium in Pinsk to complete the education begun under her village rabbi. However, her father decided to send her ahead as the first link in a “chain emigration” that would eventually bring the entire family to the United States. Alone in a new country, the young Polly fell prey to sexual exploitation and learned to survive by criminal activity, a pattern of immigration and settlement common to a minority of single Eastern European Jewish women.

Born on April 16, 1900, Pearl (Polly) Adler was the eldest of two daughters and seven sons of Gertrude (Koval) and Morris Adler of Yanow, Belorussia. Adler’s father was a tailor whose work provided comfortably for his family. When Pearl was twelve years old, her father sent her to friends in Holyoke, Massachusetts. She did housework while attending school to learn English. When World War I cut her off from her family—and the monthly stipend sent by her father—she moved in with cousins in Brooklyn, where she continued attending school as often as her job in a shirt factory allowed. At age seventeen, she was raped by her foreman. When she found herself pregnant by him, she had an abortion. After an argument with her scandalized relatives, Adler moved to Manhattan, where she continued to support herself by factory work.

In 1920, her roommate introduced her to a bootlegger who offered Adler her first opportunity in the business in which she would make her name. She began to keep an apartment furnished and paid for by the gangster. Whenever he and his married girlfriend were not there, Adler provided a rendezvous and procured women for his friends and for her own developing clientele. Her first arrest for operating a house of prostitution put an end to this arrangement in 1922. Adler used her savings to open a legitimate lingerie business, only to see it fail a year later.

Impoverished, Pearl—now Polly—returned to her career as a madam. She opened the first of a series of ever fancier brothels. Later, she opened a resort in Saratoga Springs, New York, the summer retreat of the fashionable upper-class clients she so desired. Gangsters, among them “Dutch” Schultz and Lucky Luciano, rubbed elbows in her parlors with the Manhattan haut monde, all persuaded by Adler’s well-orchestrated publicity campaign that “going to Polly’s” was the perfect end to an evening. Her oft-investigated associations with underworld figures never really damaged her glamorous image. To the public, she remained the classic American madam—a feisty, albeit disreputable, victor over adversity.

Adler remained in business through most of World War II until her last arrest in 1943 (the charges were dismissed, as usual). She then retired to Burbank, California, where she completed high school and enrolled in Los Angeles Valley College. She died of cancer in Los Angeles on June 9, 1962.

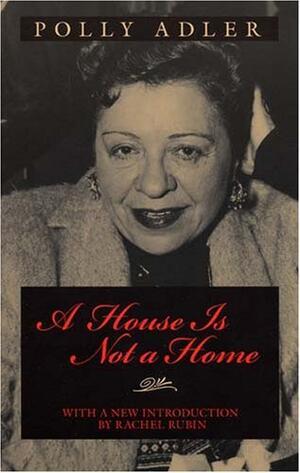

Adler, Polly, A House Is Not a Home (1953).

Berger, Meyer. “Miss Adler and Guests.” NYTimes Book Review, June 14, 1953.

Bullough, Vern. “Polly Adler.” In European Immigrant Women in the United States: A Biographical Dictionary, edited by Judy B. Litoff and Judith McDonnell (1994).

DAB 7.

Gosch, Martin A. The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano (1975).

Marcus, Jacob Rader, ed. The American Jewish Woman, 1654-1980 (1981), and The American Jewish Woman: A Documentary History (1981).

Mitgang, Herbert. The Man Who Rode the Tiger: The Life and Times of Judge Samuel Seabury (1963).

NAW modern.

Obituary. NYTimes, June 11, 1962, 65:2.

“Pollyadlery.” Review of A House Is Not a Home, by Polly Adler. Newsweek (June 8, 1953): 104.

Weinberg, Sydney Stahl. The World of Our Mothers: The Lives of Jewish Immigrant Women (1988).