Academia in Israel

In recent years, attention has been drawn to the persistent gender inequality in Israeli academia. Though women and men enter the academic tenure track at the same level, women constitute a small minority of total tenure-track faculty and their rate of advancement in the academic hierarchy is slower than that of their male colleagues. Research shows that the discrimination against women faculty is a continuous process of accumulation of obstacles and disadvantage, rather than specific barriers located only at career entry or at career’s peak. Although some positive change occurred in the position of women faculty in Israeli academia during the 1990s, questions remain about why there are so few faculty members and why progress has been so slow.

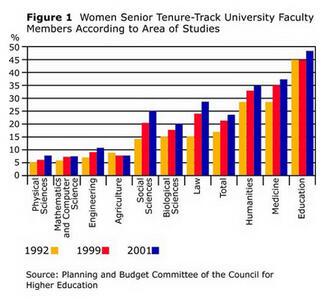

Women faculty members in the higher education system in Israel share with their sisters in other Western developed countries characteristics regarding proportions, promotions, and positions. They constitute a small minority of the total tenure-track faculty, with somewhat larger minorities in the humanities and social sciences, and very small minorities in the physical sciences and engineering. (See Figure 1.) Their rate of advancement in the academic hierarchy is slower than that of their male colleagues. Their rank distribution is in the shape of a pyramid in which a large number are concentrated at the lower ranks and only a few are at the top of the academic hierarchy. (See Table 1.)

| Academic Rank | 1979 | 1992 | 1995 | 1997 | 1999 | 2000 | 2002 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Professor | 4.6 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 10 | 10.6 |

| Associate Professor | 7.7 | 13.8 | 16 | 18.7 | 20 | 21.1 | 21.6 |

| Senior Lecturer | 16.6 | 29.8 | 30.8 | 32.9 | 32.1 | 33.1 | 33.6 |

| Lecturer | 28.9 | 37.3 | 34.7 | 36.6 | 39.6 | 43.5 | 44.7 |

| Total % of women | 16.2 | 19.9 | 20.4 | 21.8 | 22.4 | 23.9 | 24.6 |

Source: Council for Higher Education

Table 1: Women as Percentage of Total Faculty Members.

Sourced from the Council of Higher Education, courtesy of Shalvi Publishing Ltd.

Cross-nationally, women comprised between twenty and thirty percent of the regular tenure-track faculty in the early 1990s. At the same time they constituted only between seven and ten percent of the highest academic rank of full professor. In addition, women are over-represented in off-tenure tracks (temporary, part-time, parallel, and other irregular posts), in which they comprise between one-third and one-half of the total faculty. The consistent pattern of cross-national similarity is quite remarkable considering the social, cultural, economic, political, and historical differences among various countries.

Social Background

Notwithstanding the manifest sex-based differentiation in academia, there have been no studies concerning women faculty issues in Israel, whereas a large theoretical and research literature dealing with gender inequality in academia emerged in the United States and most European countries. In part, this lack of interest can be attributed to the belief that gender-based division of labor is relatively less prominent in Israeli society than elsewhere and therefore does not pose a major social problem. This assumption is based mainly on the idyllic portrayal of gender equality in the early A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim and to some extent on the service of young women in the Israeli army. As Ora Namir (former Minister of Labor and Welfare) wrote in the foreword to the Israeli report to the Beijing UN Conference on Women in 1995:

The socialist pioneering spirit of Israel in its early years perpetuated the myth that women enjoyed true equality in Israeli society. The committee I headed [Commission on the Status of Women, 1975–1978] dispelled this myth.

Since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, it seems that there have always been more pressing problems to deal with than gender equality. The pressure of predominant economic-political-social-security problems and the “myth of equality” served to divert attention from the general question of women’s status in society. Awareness of a “women’s question” and the awakening of feminist consciousness developed relatively late in Israel, some ten to fifteen years later than in other Western democratic countries.

Historical Background

The university system in Israel was founded in the mid-1920s with two small institutions of higher education—the Technion (Israel Institute of Technology) in Haifa (1924) and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (1925). For thirty years, these two universities remained the only ones in the country, specializing in different subjects: the Technion’s major field of teaching and research was engineering, while the Hebrew University’s main departments were in the humanities and sciences. After the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, five new universities were established: the Weizmann Institute of Science (1949) and the universities of Bar-Ilan (1955), Tel Aviv (1956), Haifa (1963), and Ben-Gurion in the Negev (1965).

In the 1950/51 academic year the number of students and faculty members were still very small—3,387 and 238 respectively. The next 25 years, up to the mid-1970s, were a period of great expansion. The number of faculty grew at a faster rate than the student population (for more details see Ben-David 1986; Toren and Nvo-Ingber 1989; Chen, Gottlieb and Yakir 1993). Beginning in the late 1970s this trend was reversed. According to the Statistical Report 1994 published by the Council of Higher Education, faculty appointments on the tenure-track (comprising four ranks: lecturer, senior lecturer, associate professor, and full professor) totaled 3,438 in 1983, 4,210 in 1993, 4,343 in 1995, and 4,653 in 1999. The number of students increased much more rapidly, from about 70,000 in 1990 to 100,000 in 1995 and 165,000 in 1999.

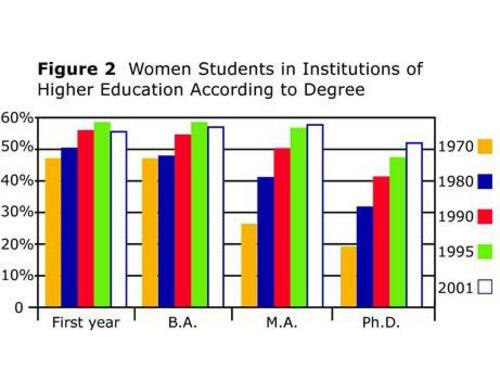

The participation of women as students in higher education has changed dramatically in most countries. At the beginning of the millennium, female students in Israel constituted over fifty percent of all students—fifty-seven percent of the B.A. students, fifty-eight percent of all Masters’ students, and fifty-one percent of all Ph.D. candidates (up from seventeen percent in 1975).

Rhetoric and Reality

Inequalities between women and men in academia should, presumably, be less pronounced than in other occupational spheres, where physical strength, mechanical skills, or leadership and authority are necessary for successful performance. Moreover, the formal structural features of academic careers are exceptionally uniform. Men and women enter the academic tenure-track at the same level, with similar human capital and credentials (a doctoral degree), do the same kind of work (teaching and research), and officially enjoy equal opportunity regarding promotion on a single, orderly career line leading to the top (Light 1974).

Notwithstanding these common structural attributes and the rhetoric of excellence, meritocracy, and collegiality proclaimed by university authorities, we find distinct career patterns of women and men in Israeli academia as well as in other countries. Three interrelated key factors color the experience of women faculty: stereotypes, numbers, and differential treatment, respectively pertaining to the dimensions of culture, structure, and behavior.

Stereotypes

Research on sex stereotypes has shown that both men and many women perceive scientists and scientific research as strongly masculine (Keller 1991; Kerr 1998). The “academic culture” defines women as less competent to engage in science and underrates their worth as scientists and scholars. Successful scientists are described as exhibiting primarily masculine characteristics, such as rationality, assertiveness, and independence (Ekehammar 1985). Women on the other hand are depicted as lacking the capabilities and appropriate attributes to do creative intellectual work. They are perceived as being emotional rather than rational, passive, insecure and dependent, and lacking the needed mathematical skills and power of abstraction. Furthermore, it is in their “nature” to be more concerned with their children and families than with the vocation of science and scholarship that demands total commitment.

Those women who dare to enter the traditionally male domain of academic research, in particular the physical sciences and engineering, find that they are marginalized, that their work and contributions are not valued as highly as those of their male counterparts, and that they have to work very hard to disprove this received opinion.

Numbers

The effects of minority group size have been studied extensively in the areas of race relations and organizations (Blalock 1967, Kanter 1977). The central question posed was whether the increase in numbers of a minority group would improve or worsen its relative status and relationships with majority members. The conclusions of these studies are not unequivocal. Some claim that the growth of a minority will be perceived as a threat by the majority and bring about more discrimination against its members (for example, the hostility and attempt of native workers to restrict entry of foreigners into the local labor market). Others propose the opposite: for example, that women will fare better in male organizations as their numerical frequency increases and their uniqueness becomes less conspicuous.

The uneven gender composition of the academic faculty—a male majority and a female minority—is a fundamental fact that affects women’s academic careers and lives, their opportunities and attainments. Nevertheless, sheer numbers are not the only reason or the major solution for gender inequality in academia. The following are a few examples to support this notion.

The empirical evidence of research on academic faculties suggests that women’s minority size is negatively related to their career advancement in terms of rank attainment (Toren and Kraus 1987). Namely, women’s academic ranks are closer to those of their male counterparts in academic disciplines in which they are represented in small proportions (i.e., the natural sciences), whereas in scientific fields in which they comprise larger proportions (i.e., the humanities) rank inequalities between genders are augmented. Another pertinent example can be found in schools of social work or education in universities, where men are a minority but nevertheless dominate the high academic and administrative ranks. Further, the famous MIT Report in 1999 “found that [in the US] though women now make up thirty-four percent of faculties nationwide, up from twenty-three percent in 1975, the gap among salaries for male and female professors actually widened in that period.” (New York Times, March 23, 1999).

Recent findings also show that in spite of the increase in the proportion of female faculty in the entry rank their subsequent career progress has not changed greatly. (See Table 1.) As put by Judith Lorber, “The numbers at the bottom in any field have little relation to the numbers at the top, where power politics is played and social policies are shaped.” (1994, p. 226). Indeed, women faculty in Israeli universities have realized that increasing the number of women is ineffective unless they participate in university governance and decision-making committees on all levels.

Thus, it is not only proportions that determine minority members’ position but also who they are (men or women), and the context in which they interact (different scientific fields). The practical conclusion of these examples is that although increasing the number of women is important it must be accompanied by real perceptual and behavioral changes in order to increase gender equality in academia.

Discrimination (Differential Treatment)

Although some changes of attitude toward gender-based inequality in Israeli academia occurred after the mid-1980s and expressions of prejudice became less frequent and blatant, unconscious and subtle forms of differential treatment restricting women’s opportunities continued to exist.

Gender discrimination in the 1990s is subtle but pervasive, and stems largely from unconscious ways of thinking that have been socialized into all of us, men and women alike.… But the consequences of these more subtle forms of discrimination are equally real and equally demoralizing. (Bailyn 1999)

The main processes that are prone to bias and manipulation are those that include judgment and decision-making concerning recruitment, tenure, and promotion (Steinberg 1992; Wenneras and Wold 1997). When making these decisions or awarding research grants, prizes, and honors, men are the traditionally favored candidates. Women are scrutinized more rigorously and stricter criteria are applied in judging their worth and merit because of the underlying stereotypes noted above. To assure himself, the chair or dean requests more supporting evidence, such as an additional reviewer or reader, which in turn results in dragging out and stretching the duration of the evaluation process of women faculty.

Other traditional perceptions play a role too. For instance, sometimes a man is preferred to a competing woman because he “is the family’s breadwinner while she has a husband who supports her and the children.” Another example of the adherence to traditional sex-based stereotypes is the story of a woman who was asked by the dean of her department to accept the promotion of a competing male colleague instead of her own “because a career is more important to him.”

Such proclamations have become less frequent, but even today presidents of Israeli universities are opposed to affirmative action in academia because they maintain that this would impair the principles of excellence and merit. They also vehemently deny that particularistic considerations such as sex, age, or ethnic or national origin are involved in the processes of hiring, firing, or promoting faculty. By comparison, orientations and policies of gender equality and equity are much more progressive within the European Union nations and the United States.

The Hurdle Track and Accumulation of Disadvantage

Research on women faculty has identified a variety of obstacles inhibiting their career development and advancement. For example, marital and parental obligations that coincide with the first crucial years of the academic career (Hargens, McCann, and Reskin 1978); the reluctance of faculty men to serve as mentors and collaborate with women students (Gibbons 1992; Etzkowitz, Kemelgor, and Uzzi 2000); limited geographical mobility; the minority status of women faculty (Toren and Kraus 1987; Long 2001); the relative absence of female role models (Astin 1985); exclusion from informal networks and some scientific specialties (Cole 1979); and gendered stereotypes and discrimination against women in academia (Lorber 1994; Valian 1998).

Different kinds of barriers are situated and become salient at different career stages and junctures. An interesting question raised by a career-cycle perspective concerns the location of major hurdles along the career trajectory. Are obstacles and barriers situated mainly at the point of recruitment and career entry? Throughout career progression? Are women stopped just before reaching the top? Or are all these interconnected and therefore so difficult to overcome?

Various metaphors have been used to describe this problem, the best known of which is the “glass ceiling.” This popular image depicts the phenomenon of women in high-status occupational areas (business, government, academia, and the military) not achieving the top levels of the organizational or professional hierarchy. Another metaphor is the “leaking pipeline” that refers to women’s dropping out during their advanced studies or in the early career stages. Others have noted that the “bottleneck” is situated at the stage of recruiting and entrance to the academic career, and so on.

The concept that best captures faculty women’s predicament is that of a “hurdle track” (Toren 2000) denoting that obstacles are recurrent, appear at various career junctures, and that their effects are interdependent and cumulative. In a review article on “Gender Inequality and Higher Education” (in the United States), Jacobs maintains that:

The notion of cumulative disadvantage seems to be a reasonable summary of the under-representation of women in faculty positions. In other words, women have been disadvantaged to some extent in every stage of the academic career process. (1996, p. 172)

At the initial entry stage cultural stereotypes and self-images have considerable influence and serve to limit recruitment by universities as well as by women’s own career choices. In the subsequent stage, when the young academician has to prove and establish her or his reputation (the first five to seven critical years), women may be impeded by childbearing and family obligations as well as by institutional arrangements that are not compatible with their special needs. Later on, in mid-career, the consequences of earlier obstacles created by overt and covert discrimination are exacerbated and disadvantage women further. Women who lagged behind when bearing and caring for young children do not usually pick up and close the gap when children grow up and are less dependent.

The concept of accumulation of disadvantage (Merton 1988) is illustrated by the well-known phenomenon in academia that women on average stay longer (number of years) in each rank than their male colleagues. Moreover, they attain each successive rank increasingly later and the rank discrepancy between genders grows over time. As a result, women often do not make it to the top, to the rank of full professor (retirement is obligatory at the age of 68). Since only relatively few reach the highest rank, they do not participate in the most important decision-making bodies and committees, a fact that negatively influences their fate and that of other women.

The discrimination against women faculty is a continuous process of accumulation of obstacles and disadvantage (a hurdle track) rather than specific barriers located only at career entry (thresholds) or at career’s peak (ceilings).

Signs of Change

Although some positive change occurred in the position of women faculty in Israeli academia during the 1990s, the questions posed long ago—Why so few? Why so slow? Why so low? (Rossi 1972)—have remained relevant.

Although a small number of women were appointed to high administrative posts such as rector, dean, department chair (and even one president of a college), women’s percentage in central university committees remained small (an average of ten percent).

The fate of the bulk of women faculty has changed little. Looking at Table 1 we can see that in the course of eight years (1992–2000) the representation of women in all ranks increased to some extent, but the basic pyramidal shape of their rank distribution was maintained (43.5 percent at the bottom, ten percent at the top). Since the entry rank of lecturer does not carry tenure, one can never foretell how many of the new recruits will be promoted to the next rank of senior lecturer and gain tenure.

Similarly, gender segregation among fields (see Figure 1) did not change to a great extent. The proportions of female faculty grew in all disciplines, particularly in the social sciences and law, but stayed relatively low in the traditionally masculine physical sciences and engineering, and high in the traditionally feminine fields of the humanities and education. The high proportion of women in the faculty of medicine was noteworthy.

These changes seem evolutionary rather than revolutionary. The report of the European Commission (January 2002) stated among its main conclusions referring to gender equality in science that

…the work accomplished to date has been considerable, but considerable inequalities still remain, and the process is very slow. The pace of change therefore needs to be tackled now.

Shifts in the level of awareness and attitudes are more difficult to measure. Faculty men generally claim that they are totally gender-blind in their evaluations and judgments; some hold on to their old ideas that it is women who are not ready or not able to engage in a demanding career such as scientific research; others are unaware of any gender-based problems in academia. In practice, men do not seem to be willing to give up entrenched privilege and power and women’s effort to change the situation more rapidly and dramatically is still an ongoing battle.

Conclusion

Working towards gender equality in the scientific community is a worthy cause because of its moral justification and also because of its potential advantages.

It is argued that women academics differ from men not only in their relationships with colleagues and students but that they “do science” differently, ask different kinds of questions, use different methods of research and approach their subject from new angles. (See Harding 1986; Bleier 1986; England 1993; Kerr 1998.)

The growing diversification of the faculty in academic institutions in terms of gender is beneficial insofar as it provides the opportunity to consider a variety of scientific perspectives and understanding, and promotes intellectual exchange and interaction that are of crucial importance for innovation and the creation of new knowledge.

Astin, Helen S. “Research Productivity Across the Life and Career-Cycles: Facilitators and Barriers for Women.” Scholarly Writing and Publishing: Issues, Problems, and Solutions, edited by Mary E. Fox, 147–160. Boulder, CO: 1985.

Bailyn, Lotte. Comments on the MIT Report, 1999.

Ben-David, Joseph . “Universities in Israel: Dilemmas of Growth, Diversification and Administration.” Studies in Higher Education 11 (1986), 105–30.

Blalock, Hubert M., Jr. Towards a Theory of Minority Group Relations. New York: 1967.

Bleier, Ruth, ed. Feminist Approaches to Science. New York: 1986.

Chen, Michael, Esther Gottlieb, and Ruth Yakir. “The Academic Profession in Israel: Continuity and Transformation.” In The International Academic Profession, 617–666; Princeton, N.J.: 1996.

Cole, Jonathan R. Fair Science: Women in the Scientific Community. New York: 1979.

Ekehammar, B. “Women and Research: Perceptions, Attitudes, and Choice in Sweden.” Higher Education 14 (1985): 693–721.

England, Paula, ed. “Introduction” In Theory on Gender/Feminism on Theory, 3–24. New York: 1993.

Etzkowitz, Henry, Carol Kemelgore and Brian Uzzi, Athena Unbound: The Advancement of Women in Science and Technology. Cambridge, England: 2000.

Gibbons, A. “Mentoring.” Science (1992), vol. 255: 1368.

Harding, Sandra. The Science Question in Feminism. Ithaca, N.Y., and London: 1986.

Hargens, L.L., McCann, J.C., and Reskin, B. “Productivity and Reproductivity: Fertility and Professional Achievement among Research Scientists.” In Social Forces (1978): 154–163.

Jacobs, Jerry A. “Gender Inequality and Higher Education.” Annual Review of Sociology, 22 (1996):153–185.

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. Men and Women of the Corporation. New York: 1977.

Keller, Evelyn F. “The Wo/Man Scientist: Issues of Sex and Gender in the Pursuit of Science.” Edited by Harriet Zuckerman, Jonathan R. Cole, and John T. Bruer, 227–236. In The Outer Circle: Women in the Scientific Community. New Haven: 1991.

Kerr, Anne E. “Toward A Feminist Natural Science: Linking Theory and Practice.” Women’s Studies International Forum 21 (1998):95–109.

Light, Donald. “The Structure of the Academic Profession.” Sociology of Education 47 (1974): 2–28.

Long, Scott J., ed. From Scarcity to Visibility: Gender Differences in the Careers of Doctoral Scientists and Engineers. Washington D.C.: 2001.

Lorber, Judith. Paradoxes of Gender. New Haven: 1994.

Merton, Robert K. “The Matthew Effect in Science II, Cumulative Advantage and Symbolism of Intellectual Priority.” Isis 79 (1988):606–623.

Rossi, Alice S. “Women in Science¾Why So Few?” In Toward a Sociology of Women, edited by C. Safilios-Rothschild, 141–153. Lexington, Mass: 1972.

Steinberg, Ronni J. “Gendered Instructions: Cultural Lag and Gender Bias in the Hay System of Job Evaluation. Work and Occupations 19 (1992): 387–423.

Toren, Nina. Hurdles in the Halls of Science: The Israeli Case. Lanham: 2000.

Toren, Nina and Judith Nvo-Ingber. “Organizational Response to Decline in the Academic Marketplace.” Higher Education (1989) 18:149–165.

Toren, Nina and Vered Kraus 1987. “The Effects of Minority Size on Women’s Position in Academia.” Social Forces (1987) 65:1090–1100.

Toren, Nina and Judith Nvo-Ingber. “Organizational Response to Decline in the Academic Marketplace.” Higher Education, 18 (1989):149–165.

Valian, Virginia. Why So Slow: The Advancement of Women. Cambridge: 1998; Wenneras, Christine, and Agnes Wold. “Nepotism and Sexism in Peer-Review.” Nature (1997) 387:341–343.