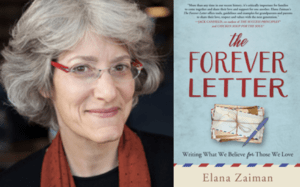

Writing Forever Letters with Rabbi Elana Zaiman

Elana Zaiman was the first woman rabbi in a family chain of rabbis spanning six generations. Growing up in a traditional Conservative synagogue where women were not allowed to read from the Torah, Rabbi Zaiman’s decision to become a rabbi and forward a new iteration of her family’s legacy made her a pioneer in her family history. Her book and project, The Forever Letter puts a modern spin on the medieval idea of an ethical will. JWA sat down with Rabbi Zaiman to talk about family, the importance of writing forever letters, and bringing this medieval tradition into the 21st century.

What has been your experience being the first female rabbi in a family spanning six generations of male rabbis?

I think the biggest issue for me to overcome when I became a rabbi was, “Am I valid?” Could I, as a woman, be a rabbi? Not just could I possess the title rabbi, but could I be a “real” rabbi?

My grandfather was an Orthodox rabbi in a modern Orthodox synagogue. My father was a Conservative rabbi in a traditional Conservative synagogue. In these settings, women did not read from the Torah, were not called up to the Torah to recite an aliyah, and could not lead the community in prayer.

As a child, I attended an Orthodox Jewish day school where girls could not participate in communal rituals either. At some point along the way, I found myself wishing I could lead services. I could pray fluently in Hebrew, I had a nice voice, I prayed with intention, and I was spiritually moved by the melodies, more so than most of my male classmates. Yet, I did not question. I accepted tradition.

The Jewish Theological Seminary began to ordain women in 1984.Four years later I applied to rabbinical school. When I sent in my application, I imagined my Orthodox grandfather saying, “A woman becoming a rabbi. What’s this world coming to?” While my father supported my decision to apply, I sensed it made him a little uncomfortable too. In part because of his background, and in part because he was worried about the difficult road ahead for his daughter. Would she find a job?

For me, becoming a rabbi was not just about being validated by a community getting the go-ahead from the Conservative movement, etc). For me, it was coming to believe within myself that I was a rabbi, a real rabbi. This took me many years.

In your new book, The Forever Letter, you take the medieval Jewish tradition of the “ethical will” and put a modern spin on it. How did you develop the idea of the Forever Letter and why is it so important?

The concept of the forever letter began many years ago when I started teaching and speaking about “ethical wills.” Ethical Wills was the name given to letters written by parents to children passing on ethical and ritual values and traditions. The Hebrew word for these letters was tze-vah-oat or commandments, and many of them were just that: commandments. It’s believed that the term ethical wills was coined by Israel Abrahams who, in the early 1900’s, collected and translated many of these letters into a volume he called Hebrew Ethical Wills.

Some of these parents wrote their ethical wills when their children were young and added to them over the years. Others wrote before taking long trips, fearful of their safe return. And still others wrote as they aged, unsure how much time they had left to live. So, for many of those writing, there was a sense of urgency, a desire to get down in writing what was most important to them.

For years, I was teaching about ethical wills without understanding that I was really developing a new kind of letter that was inspired by, but different to, the ethical will. I call this letter “the forever letter.”

Forever letters can be written by parents to their children, and they can also be written by grandparents to grandchildren, spouses and partners to one another, siblings and friends to one another, children to their parents and grandparents, teachers to their students, and students to their teachers. The point is that we all have important things to share with the people we love.

Forever letters pick up on the sense of urgency. Since we never know how much time we have left on this earth, it’s important to tell the people we love what matters to us most. I usually offer three questions as a way of thinking about forever letters.

- What do I most want to tell the people I love about me?

- What do I most want to tell the people I love about them?

- What do I most want to tell the people I love about the relationship we share?

While forever letters are about putting our values and wisdom on the page, they are also about sharing our love and appreciation, asking for and offering forgiveness in a heartfelt and loving way, and being emotionally, spiritually, and psychologically attuned to the people we are writing to. Forever letters are not about using harsh tones and issuing commandments, nor are they about side-stepping hard issues. Rather, they are about stating hard truths with love.

My intention is that we send, deliver, or give our forever letters while we are living so that we can tend to our relationships, and perhaps even heal relationships that have gone awry. Writing forever letters offers the possibility of opening a door. A door that may be open already with verbal daily, weekly, monthly or yearly communication, or a door that may have been shut for years. If we are writing a letter to someone with whom we have a complicated relationship, there’s a chance that our words can begin to bridge a previously held distance.

I can’t overstate the importance of writing forever letters in this day of the tweet and text. Society moves so fast. Our ability to reflect on what really matters is becoming a lost art. Writing forever letters gives us the opportunity to reflect on ourselves, our lives, the people in our lives, and our relationships. This is the beauty of a forever letter. It affords us an opportunity to revisit the pieces of our lives that matter with the people in our lives who matter.

As you have been traveling and teaching on this topic, can you share a moment that has resonated with you?

Here’s one moment: I recently spoke at a retirement community where my book was being sold. In line, a gentleman in his late 80’s early 90’s was holding four books. “Wow,” I said. “ Why four books?” He smiled, even gave a little chuckle. “One for me and one for each of my three kids. I want them to write me letters.” It’s not just kids who want to hear from their parents. Parents want to hear from their kids. Most of us long to hear from the people we love. So, pick up a pen or put your hands to the keyboard and begin.

One final question. What advice do you have for women who want to be rabbis or pursue careers in other male-dominated fields?

Go for it. Believe in yourself. Believe your contributions matter. If you are pursuing what you want to do, do it. Don’t hold back. Push the envelope. Before me, there were many who pushed the envelopes in their careers as doctors, lawyers, even rabbis. There were many women who pushed for reforms in our world, reforms for the mentally ill, for the desegregation of buses, for the right of women to vote. I am just following in the paths created by the inspirational and courageous women who came before me.

Thank you for posting this great teaching