The Women Who Fought for Pacifism

On November 1, 1961, 50,000 women in 60 cities across the United States walked out of their jobs and homes to protest nuclear proliferation. With the slogan “End the Arms Race, not the Human Race,” they communicated their many fears about nuclear war including the threat of irradiated breast milk poisoning their children.

This walkout marked the birth of pacifist group Women Strike for Peace. After the initial strike, the group went on to lobby against the Vietnam War, and launch the career of superstar Bella Abzug. The organization continued to speak out against war and American involvement in Latin America and the Middle East in the 1980s and 1990s, and remains active today. Thanks to its decades-long fight for an end to both nuclear proliferation and violent intervention overseas, Women Strike for Peace has established itself as one of the most prominent pacifist groups in the United States.

But what about the women who were passionate about peace but had no involvement in this big-name organization? What can we glean from their stories?

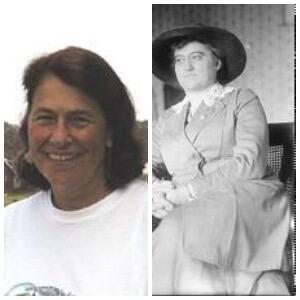

Rosika Schwimmer was one such woman; in fact, she died before Women Strike for Peace was even founded. An early pacifist, Schwimmer was born in Hungary in 1877 and became an advocate for women's rights there; while living in London during the outbreak of World War I, she began agitating for peace.

Schwimmer's brand of peaceful agitation relied heavily on tenacity, boldness, and a total disregard for what others thought about her. First, she met with American president Woodrow Wilson, asking him to mediate between the Allied and Central powers as a neutral party. When that didn't work, she founded the Women's Peace Party in the United States and continued to meet with leaders of both warring and neutral countries to ask them to end the war. When Schwimmer failed to drum up interest in her pacifist project among any world governments, she resorted to the private sector. She persuaded Henry Ford—yes, that Henry Ford—to back an expedition to Stockholm to meet with an international peace delegation there. The ship carrying the delegation from the United States was derisively dubbed the “Peace Ship” by the American media, whose special combination of anti-Semitism and anti-feminism ripped Schwimmer apart.

One wonders whether world leaders and the media alike would have been more receptive to Schwimmer’s message if she hailed from a different demographic group. After all, she was hardly the first pacifist; thinkers and intellectuals as prominent as Leo Tolstoy had been advocating for peace instead of violence since the mid-nineteenth century. But for whatever reason, after the ridicule heaped upon her by the media and others for her pacifist agitating, Schwimmer’s career never recovered. Post-World War I, she embarked on a short diplomatic career as a minister in Switzerland for the Hungarian government. But when communists took over Hungary in 1920, she fled, returning to the United States, where she faced vitriol from both right-wingers who viewed her as a foreign agitator and from Jewish groups who claimed that she had somehow turned Henry Ford into an anti-Semite.

Schwimmer's story is a reminder of an unfortunate truth: sometimes, following your passions and your heart don't pay off in the form of success, awards, or even respect. But here's another reminder: despite all these setbacks, Schwimmer fought for world peace until the day she died in 1948. Rather than a harbinger of pessimism and defeat, Schwimmer's story stands as a reminder that although we may never receive the results or validation that we want for our activism, we should never, ever give up.

Sally Mack, another pacifist from outside the Women Strike for Peace umbrella, also has an unconventional story. But unlike Schwimmer, whose story ended in an unusually sad way, Mack's began in an unusual way. Mack, a social worker who was born in 1933, raised her children with a sense of activism and a belief in non-violence. Her children took those messages to heart, perhaps more than she expected: in 1986, her youngest son brought his siblings and parents to Mercury, Nevada to protest a nuclear site there. This episode ended in the whole family's arrest, and Mack ended up spending five days in jail.

Whereas some middle-aged mothers might have chastised their children for putting the whole family in such a situation, Mack had the opposite reaction. The protest and her arrest sparked a later-in-life commitment to the pacifist movement. She founded the group Families in Action in the Nuclear Age and she started assuming leadership roles in other social justice movements. Her story is a reminder that our calling as activists might not come from the source we expect, or at the time of our lives that we expect, but it's possible to always remain open to new causes and fights.

Although the well-known story of Women Strike for Peace is inspirational for many activists, it's also important to reflect on the lesser-known stories of pacifist women who had unusual experiences within this movement. Whether we're reflecting on Schwimmer's tenacity in the face of repeated and utter defeat or on Mack's open-mindedness in the face of an unexpected arrest, these stories can help us shape our own activism and remind us that although social justice might not look the way we expect it to, it's never the wrong time to fight for the causes we know to be right.