Women Shaping Jewish Life in Germany

Jewish women are at the forefront of many positive social change initiatives in Germany today, helping to broaden spaces for Jewish expression. One such initiative is SchumZoom, an online egalitarian chavurah founded by Annette Boeckler during the pandemic. “It’s no accident that women are very present here,” said Boeckler in a German radio interview. “Jewish women tend to seek an active Jewish life, and at SchumZoom they have the opportunity to help plan and shape all our activities.”

At Limmud Germany’s June 2023 festival in Hanover, women led many of the sessions on contemporary topics such as sexuality and sanctity, Ashkenazi herbalism, and Jewish superheroes in pop culture. The festival had a lively atmosphere that you don’t always find at Jewish events in Germany, which tend to revolve around the Holocaust, remembrance culture and antisemitism.

At the Imagined Futures workshop that we facilitated, Limmudniks eagerly shared their views on how to expand Jewish spaces and change the dominant discourse about Jewish life in Germany. Many expressed their frustration with the prevalent representation of Germany’s Jews as victims in constant danger from extremist threats, while others lamented the fact that “there is often more attention paid to dead Jews than living ones.” Some also felt the Jewish community’s hyper-focus on antisemitism is counterproductive, because it keeps the public from learning more about positive aspects of Jewish life.

Germany now has one of the most diverse Jewish populations worldwide. Thousands of young Israelis have moved to Berlin, others are now adult children of the wave of parents who came from the former Soviet Union in the 1990s, some have moved from the US or Canada, and a minority have been in Germany for generations.

Despite the rich diversity of Germany’s Jewish population, some of the community’s female activists struggle to implement their projects and initiatives. Some work with support from the Central Council of Jews in Germany, the official representative of Germany’s Jews, but others find the conservative tendencies of the Central Council and its regional affiliates too restrictive a home for their ideas.

Some progressive Jewish women we interviewed in Berlin and at the Limmud gathering expressed their frustration with trying to get support for Jewish artistic endeavors that fall outside of a conservative or traditional Jewish orientation. Rachel Libeskind, the Creative Director at LABA Berlin, an incubator for Jewish art, criticized the fact that “Jewish projects here must be caught in a web of organized religion to succeed,” something that in her experience is not true in the United States.

Rabbi Elisa Klapheck, leader of Frankfurt am Main’s Egalitarian Minyan, places herself firmly within German Jewry’s existing institutional structures. Klapheck sees herself as part of the first generation to rebuild Jewish life after the Shoah and counsels patience to those seeking greater expansion of Jewish spaces in Germany. One of the founders of the Jewish women’s initiative Bet Debora, Klapheck has been actively promoting the revival of Jewish life and the role of women in Germany’s Jewish communities since the 1990s.

The M.S. Goldberg Jewish Theater Ship is another focal point for the revival and expansion of Jewish culture in Germany. With a wide range of traditional and modern performances that appeal to Jews and non-Jews of all ages, the theater ship is presenting a new face of Judaism to a broad public along the waterways of Berlin and beyond. Judith Kessler, publicist and performer for the theater ship, explains that the ship’s program presents such diverse facets of Jewish culture that it serves to break down stereotypes about Jews. This fits with Kessler’s desire “not to be categorized, but seen as a normal person.”

Jalda Rebling, a prominent cantor and founder of congregation Ohel Hachidusch, argues for embedding Jewish life in Germany into a more contemporary discussion about other minority groups. “The pervasive culture of remembrance can stifle positive change,” she says. These events, Rebling asserts, give people an emotional moment of commemoration but produce no meaning beyond. Instead, “we should look at what people’s needs are today.” As the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, she feels she can speak with authority about Germany’s horrendous past. Rebling advocates for building grassroots Jewish communities that sustain themselves, as she has done with Ohel Hachidusch.

Changing the narrative about Germany’s Jews also includes programs for the very young. That’s what’s happening at the Bubales Puppet Theater. Founded by Shlomit Tripp, the theater stages performances simultaneously in German, Turkish, Arabic, and sometimes Hebrew and Ukrainian. Tripp, born to Turkish Jewish parents, describes herself as “radically intercultural” and therefore eminently suited to building bridges. Her successful shows engage children as young as six with fun, positive aspects of Jewish life. Muslim mothers wearing hijabs sit side by side with Jewish parents and parents of children from a wide range of backgrounds. Young children sit in rapt attention for shows that last over an hour.

This is just a taste of the many initiatives that are expanding spaces for Jewish self-expression in Germany today. The small but vibrant Jewish community, with many women at the forefront, is shifting perceptions from the past towards the future and broadening the discourse to reflect a wider range of Jewish interests.

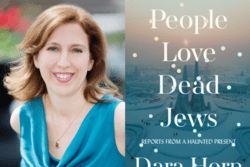

I am looking forward to hearing the author speak about her fascinating new book which I have started reading.