Why Don't Americans Celebrate Shavuot?

One of the first things I learned about Shavuot is that it is, in the words of dozens of Jewish publications, “undercelebrated”—at least in the United States. If you Google “Why don’t Americans celebrate Shavuot?” you’ll get dozens of results with headlines that mirror the query word for word. Ari M. Brostoff, writing for Tablet Magazine, points to a few possible reasons for the holiday’s lack of recognition in America, including hazy associations between the holiday itself and what it purports to celebrate. “In its earliest incarnation,” they write, “Shavuot marked a pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the sacrifice of the harvest’s first fruits and is one of a historical trio of harvest celebrations, along with Sukkot and Passover, known as the shalosh regalim.” They go on to cite Paul Steinberg, who notes that “rabbis in the Talmudic period needed to reinvent Shavuot after the Jews left Israel for the Diaspora and no longer traveled to Jerusalem with harvest offerings.” Steinberg explains that the sages ultimately decided to associate Shavuot with the giving of the Torah, but this attempt to make the holiday more germane to the lives of Diaspora Jews, including Americans, clearly hasn’t worked.

As is so often the case, I discovered the degree of my own lack of understanding of Shavuot when I was asked by a non-Jewish friend to explain the holiday. “It’s when we read the Book of Ruth,” I texted her. “So where do the blintzes come in?” she responded. “Not sure,” I replied. “Oh! It’s also when we received the Torah from Mount Sinai and became Jews!” She followed up: “That seems extremely important.” I don’t disagree.

The conversation spurred me to think more deeply about how I usually communicate my understanding of Jewish holidays and practices. I realized that when I’m explaining my culture, I almost always find a political angle or connection to a broader theme of justice and resilience. As someone who has chosen to live a Jewish life—I am patrilineally Jewish, and thus my Jewishness is something I have felt the need to fight for—I am, like many others, deeply moved by the Book of Ruth, which models choosing Judaism and Jewish life. But I’ve never actively celebrated Shavuot, and most of my Jewish friends and family haven’t either. Holidays like Purim and Hanukkah both have messages that dovetail easily with ritual, tradition, and secular ideas of justice: fighting oppression, the survival of the Jewish people. For these celebrations, there are items available at major big box stores to purchase, and scripts to follow. Passover offers us themes that are easy to extrapolate and bend in whatever fashion feels the most necessary and appropriate—there are hundreds, if not thousands, of Haggadot that help Jews celebrate Pesach through a host of lenses: queer, feminist, Marxist.

The lack of material connection to the holiday and the absence of a script for home rituals are undoubtedly reasons for Shavuot’s lack of observance in the US. “Shavuot is the consummate rabbis’ holiday,” Brostoff writes in Tablet. “Its difficult themes of revelation, law, and collective responsibility make it a favorite among scholars—who struggle with how to share their enthusiasm with the laity.”

I reached out to Rabbi Emily Losben-Ostrov, the leader of the oldest congregation in North Carolina and the woman overseeing my walk to the mikveh this fall as I prepare for my wedding, to ask her what excites her about Shavuot, and how she sees that enthusiasm reflected back from her congregation. She responded:

I love the emphasis on Torah and more specifically that each of us personally receives Torah—that the Torah is revealed to each and every Jew. With that sense of revelation there is the opportunity to make Torah personal, to study the teachings of Torah and Jewish teaching in general... I love the concept of tikkun leil shavuot—of staying up late (or even all night) to delve into Jewish learning. I have been truly energized from my community who join me until 11:00 p.m. or 2:00 a.m. or even daybreak to continue studying—whether it's the Book of Ruth, the Ten Commandments or even something somewhat obscure.

I’m hardly the first person to wonder about the possibilities of re-interpreting and re-imagining Shavuot for this political moment. Elana Spivack wrote an incredibly moving piece for JWA on queerness in the Book of Ruth just last year. But Rabbi Emily pointed to a message so obviously present in Shavuot that I was embarrassed I’d overlooked it. “I think the most important political lesson to glean from Shavuot,” she said, “is that of acceptance. I often focus on the symbolic teaching that we were all present at Sinai—that every Jew has an equal share in our faith, an equal share in the joy of being Jewish. This is further punctuated by the reading of Ruth and the celebration of those who have chosen of their own free will to become Jewish. Shavuot is a great opportunity to remind ourselves that we must treat all Jews equally, as well.”

Individual observance and celebration will always be less flashy and participatory than more community-based holidays—but that isn’t an inherently negative thing. Whether or not you read the Book of Ruth or commit to grappling with the relevance and application of the Torah to our everyday lives is, in many ways, secondary to centering acceptance in this season—of your life, of this month, of this Jewish year. Accept yourself as a Jew in whatever form feels right to you. Accept your Jewish neighbor, regardless of how they came to their Judaism. Accept abundance, the shift in the air that signals the coming of summer. Celebrate the mundane, because every moment of your life is deserving of reflection and gratitude. And go ahead—eat a blintz.

For Christians, it was the day the disciples received the Holy Spirit. It's just that the corrupt roman church and constantine instituted false holidays such as easter and Pentacost. The Moedim are the true days about Yeshua, ie: He was the Passover Lamb, He rose on First Fruits, was born on Sukkot, circumcised on Sh'mini Atzeret, etc.

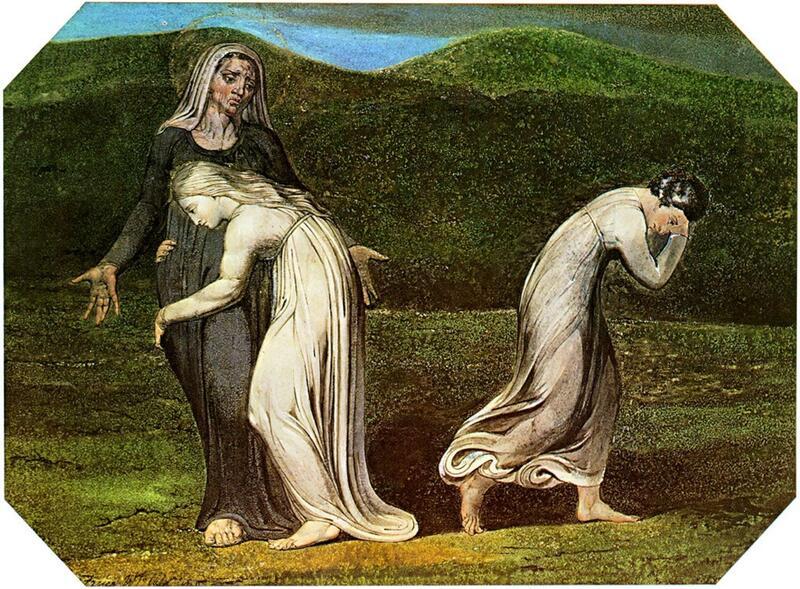

I like this reading; many thanks! The Book of Ruth stresses acceptance as a major theme, absolutely. And there's more: Ruth is choosing to value her relationship with her mother in law, not casting her off as an old woman of no further use because she has lost all her male relatives and is past menopause. So, infertility and the imminent extinction of the family is a theme. Age is a theme. Valuing wise older women and family and established love relationships over the restless search for new ones is a theme. Ruth chooses matriarchy over a return to familiar paternal control among her own people. She commits her life to strangers, to her mother-in-law's unselfish love, and to her G-d. "Whither thou goest, I will go." It is an extraordinary moment, worthy of a holiday in and of itself. Then and there Ruth accepts the Torah — and makes possible King David! A git yontif ale!