Why do we act? Lessons from the Freedom Rides

Fifty years ago, in May 1961, a small group of civil rights activists embarked on a journey that would change them and change America. Boarding buses headed south for what they termed a "Freedom Ride," these young black and white activists challenged segregation by sitting together on the bus and in the waiting rooms of bus stations. Though the Supreme Court had already declared segregation in interstate travel illegal, the Federal Government was not enforcing the law, so the Freedom Riders engaged in nonviolent civil disobedience to call attention to this injustice. They were met with violent mobs throughout Alabama and Mississippi, often brutally beaten in the presence of police and FBI agents who did nothing to stop their attackers.

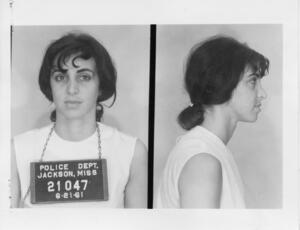

When violence and arrest disbanded the initial group, new volunteers--mostly students--took their places. If they couldn't avoid arrest, they could initiate a new strategy: filling the jails. Buses of activists from all over the country joined the Freedom Rides, and during the summer, more than 300 Freedom Riders were arrested in Jackson, where they refused bail and instead filled the jails, facing beatings, harassment, and deplorable conditions. (A new documentary by American Experience about the Freedom Riders premieres on PBS this month. And this week, a group of college students and original Freedom Riders are retracing the 1961 journey.)

More than half of the white Freedom Riders were Jewish, and Judith Frieze, a recent graduate of Smith College, was among those white northerners and many Jews who joined the Freedom Rides in the summer of 1961. Arrested in Jackson, she spent six weeks in a maximum security prison. In a series of articles she published in the Boston Globe after her release, she recalled what motivated her to join the Freedom Rides: "All of a sudden I was tired of talking. I had reached the point when I wanted to do something about this. I felt like the only way that I could make my principles meaningful was by involving myself... It seemed necessary to close that gap between what I was saying and what I was doing." [Emphasis in the original.]

Idealism was not her only motivation. She also admits she drawn to participate in the Freedom Rides by a "longing for adventure." Frieze was not eager to return home to live with her parents, as unmarried women were expected to do at the time, and the Civil Rights Movement gave her another option: to go south and do something that felt meaningful and exciting.

The activists suffered in jail; Frieze, for example, was not allowed to take her asthma medication and got quite sick. But she also recalls the camaraderie that she and her fellow Freedom Riders shared: "We spent most of our time... getting to know each other," she wrote later that summer. "At first we knew our new Negro friends by voice only. We had no way of seeing them. [They were in other cells since the jail was segregated.] But dipping into our pool of contraband articles, we came up with a compact mirror. Now we could see each other. By holding the mirror out in the hallway between the two cells, those in one cell could see into the next. In this way, we were able to ‘introduce' ourselves to each other."

Eventually, Frieze was released from jail and returned home to Boston and to social work school. A few months later, the Justice Department pressured the Interstate Commerce Commission to issue clear rules prohibiting segregation in interstate travel. Many of the Freedom Riders went on to activism and leadership within SNCC and other parts of the Civil Rights Movement. Judy Frieze--now Judy Wright--returned to Mississippi three years later with her new husband to spend a year working with the Civil Rights Movement in Meridian. In later years, she got involved in the antiwar movement, counseling young men on how resist the draft; with the women's movement, organizing consciousness-raising groups; and with AIDS activism.

Judy's experience as a Freedom Rider was short but intense, scary but exhilarating, simultaneously disorienting and clarifying. Like many other young Jewish activists at the time, she began her journey south with a solid foundation of justice values imbued by her family as well as an emerging but still inchoate yearning for something more. She explained in an interview, "Especially when you grew up in the 50s, life could seem like it was very nice but you want something to grab onto, something that would have some importance... I had such a wonderful, wonderful family. And yet I always longed for some real purpose." Her time in prison gave her more clarity about that purpose, forging a lifelong commitment to justice and social change. The stories of Freedom Riders like Judy reveal important insights about activism--how it can turn fear into friendship, how it answers personal needs as well as communal needs, how it sparks individual as well as social transformation.

JWA has developed a lesson plan on Civil Disobedience and the Freedom Rides based on Judy Frieze Wright's story. It is part of JWA's Living the Legacy curriculum.