Why Be Jewish? Sharing stories, pushing boundaries

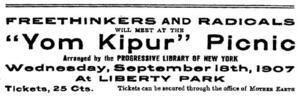

Emma Goldman's non-traditional relationship to Jewish practice is evidenced by her participation in events such as this, scheduled on Jewish holy days.

Freethinkers and Radicals

Will Meet at the "Yom Kipur" Picnic

Arranged by the Progressive Library of New York

Wednesday, September 18th, 1907

At Liberty Park

Tickets, 25 cts. Tickets can be secured through the office of Mother Earth

Last week, I had the privilege of participating in a small, intense, and invigorating conference run by the Samuel Bronfman Foundation in partnership with the Shalom Hartman Institute. Provocatively titled “Why Be Jewish?” this year’s conference focused on the state of pluralism in the Jewish community.

Unlike many conferences I attend, which have lofty (but usually unattained) goals of outlining new policies and directions for the Jewish community, this one set out a different mission: to study together, sharing personal stories and Jewish texts as a foundation for meaningful conversation and connection.

Conversations about pluralism have been an explicit part of my Jewish life since my first encounter with the Samuel Bronfman Foundation as a 16-year-old fellow on the Bronfman Youth Fellowships in Israel, and (I later came to understand) also shaped my Jewish childhood in the Havurah movement in New York City in the 1970s and 80s. Thanks to my upbringing and the investment of the Bronfman foundation, I have continued to place pluralism and pluralistic institutions at the center of my Jewish life.

Today, the concept of pluralism is no longer radical in the way it was when I was growing up; in fact, it’s often taken for granted, given lip service as one of the values of many Jewish institutions. But there’s little exploration of what pluralism means and how to engage with it as a core Jewish value—to live it, not just speak the diluted language of pluralism.

Among the central questions at the heart of pluralism is: who is included? (Or, to put this question in the negative: what are the limits of pluralism? Who is beyond the boundary?) Edgar Bronfman, writing about the conference his foundation sponsors, defined Jewish pluralism as “finding your place in the story of the Jewish people.” His definition explains why my work as a public historian at the Jewish Women’s Archive is essentially pluralistic: my task every day is to create a more expansive and inclusive Jewish story, one in which it will be easier for people to find themselves and their life experiences reflected. This means including the voices of women as well as men, of secular and religious, of gay and straight, of the working class and the affluent, of Sephardi, Mizrahi, and Ashkenazi, of Jews from birth and Jews by choice, of the unknown and the celebrated.

As a historian, I approach this challenge through texts, seeking primary sources through which we can hear the rich and multivocal stories of American Jews. So it was a particular joy to devote the two days of the conference to text study. In each session, we broke into pairs or small groups to unpack Jewish texts (primary biblical and rabbinic) together, using them as a meeting place where participants of diverse backgrounds could come together, share perspectives, and begin conversations that took us off the page and back into the 21st century.

Of course, though I was energized by the immersion in classical sources, my head was also swimming with modern texts from my day-to-day work that resonated with the themes we were exploring together. The one that most insistently emerged is an advertisement for a 1907 event put together by Emma Goldman and other freethinking radicals: a Yom Kippur picnic.

What text could better pose that persistent pluralistic question about boundaries? On the one hand, a picnic on Yom Kippur—traditionally a fast day—is obviously designed to flout Jewish practice. One might argue that anyone who publicly declares a picnic on Yom Kippur is deliberately placing herself outside of the Jewish community. And yet, in explicitly naming it a Yom Kippur picnic, weren’t Goldman and her colleagues also choosing to place themselves within a Jewish framework? After all, they could have simply called it a freethinker’s picnic or held it on a different day. But instead they announced a Yom Kippur picnic—a new, albeit totally untraditional, way to mark this significant day on the Jewish calendar with their people (in a world in which “freethinker” and “radical” was often synonymous with “Jew.”)

One of Donniel Hartman’s powerful teachings at the conference was that “The collective of the Jewish people is a source of Torah.” Meaning, what Jews do helps constitute what Judaism is. This statement provides a compelling argument for pluralism, pushing us to embrace a wide collective as the source of revelation and insight, rather than looking to some higher, external authority to determine the boundaries of acceptability and belonging. And this is why I encourage Jewish educators to teach the Yom Kippur picnic advertisement as a quintessentially Jewish text—one which helps us grapple with the central questions of what it means to live as a Jew in a pluralistic community.

Well- I am going for it. On Yom Kippor for a Teen discussion group. I will also use Ray Frank's Sermon. Both women radical, in their own way. Will report back.