Why Are Women Left Out of Jewish Genealogy?

It’s no secret that Jews like genealogy; in fact, several genealogy sites, including MyHeritage, 23andMe, Geni, and JewishGen, were created by Jews. These sites offer a wealth of information: JewishGen, for example, has over 21 million Jewish records, a community database with information on over 6,000 Jewish communities, and a Holocaust database with over 2.75 million entries, including concentration camp lists, transport lists, ghetto records, census lists, and identification cards.

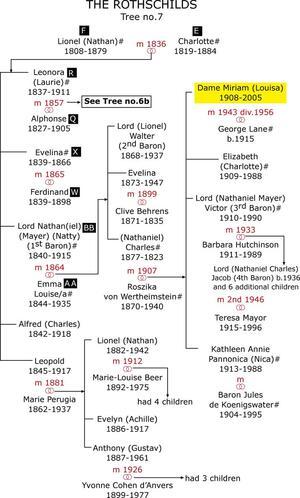

Even with this plethora of data, women are sometimes overlooked in Jewish genealogy. Often, they’re referred to without names, only as someone’s wife or mother. This makes it very difficult to trace women and learn about them through genealogical records; as a result, their stories get lost. With all the information Jewish genealogical sites offer, why are women so often left out?

Like other Abrahamic religions, Judaism is rooted in patriarchal ideas and conventions. Isaac is the son of Abraham, Jacob is the son of Isaac, and so on. It wasn’t until Maimonides’ Code of Law and Ethics (Mishneh Torah) in the twelfth century that children were deemed Jewish if their mother was, a shift from patrilineal to matrilineal descent. This change was practical, rather than ideological: in order to know if a child is Jewish, it makes sense to look at the mother, whose identity is much easier to ascertain.

Other patriarchal conventions and ideas remain ingrained in traditional Judaism, including the use of male pronouns to refer to God and the inclusion of many female characters in the Tanakh who lack agency, starting at the very beginning, with Eve. Also, according to Jewish tradition, Kohanim (descendants of the sons of Aaron) and Levites (descendants of the tribe of Levi) can only be male, as the status is transmitted from father to son. This means that women are excluded from certain duties and privileges bestowed on these groups. Given these patriarchal tendencies, perhaps it’s not surprising that women’s names are often left out of Jewish genealogical records.

Another place we can see the omission of women is in the genealogical records of rabbis. Due to the importance of rabbis in Jewish tradition, their records have been particularly well recorded and preserved. As a descendant of Judah Loew ben Bezalel (also known as the Maharal of Prague), I have quite a few rabbinic dynasties woven into my family tree. Female members of these families are rarely named. Unmarried women are referred to as “bat” (daughter of), followed by their father’s name. If they were married, often to a rabbi, they’re referred to as the wife of said rabbi. This convention can be seen in contemporary Jewish tradition, too; a Jewish child is “ben” (son of) or “bat” (daughter of), followed by the father’s name (although in more egalitarian congregations, the mother’s name is included after the father’s).

There are some exceptions to these patriarchal conventions, however. In Eastern Europe (especially countries such as Russia and Belarus), male and female children from the same family were sometimes given different surnames. For example, the surname Shapiro was changed to Shapira for women. In my family tree, a man by the name of Lejba Raczkowski had sons with the surname Raczkowski and daughters with the surname Raczkowska. It’s important to note, though, that the feminine versions of surnames would never be passed on, since wives took their husbands’ last names.

So…is that it? Are women left out of Jewish genealogy, making them almost impossible to research? Not always. Historical trends and events led to different naming conventions for Jews in different places. The Russian Empire, for example, had very different naming conventions compared to other places Jews lived. There, surnames came from the mother’s first name. For example, the surnames Glick and Gluck come from the female name Glickl. Other examples include Goldman (Golda), Beiles (Beila), Zeitis (Zeitl), and Mirls (Miriam). Similarly, the surname Margolis for Lithuanian Jews and Margulis for Polish and Ukrainian Jews derive from the female name Margalit.

Only the Russian Empire—which includes modern-day Russia, Belorussia, Ukraine, and parts of Poland—used matronymic surnames. Jews in other parts of Europe had different naming conventions. For example, Sephardic Jews, specifically those from the Iberian Peninsula, adopted surnames beginning in the tenth and eleventh centuries; these names were often based on place of origin, such as Halpern (from Helbronn, Germany) and Warszawsky (from Warsaw, Poland). Jews from Western and Central Europe also already had surnames, often ones they had chosen from a limited set of options. For example, in the eighteenth century, many European nations, including the Holy Roman Empire, passed laws requiring Jews to adopt legal surnames, often providing choices such as Schwartz (black), Weiss (white), Gross (large), and Klein (small). Yet in Russia, the matronymic convention persisted.

Why were matronymics used at all in Jewish naming conventions? After all, this wasn’t common among other religious or ethnic groups. The dominant theory is that it was related to economic and social structures in Eastern EuropeN Jewish communities. As men studied in yeshivas, women were more involved in public life, running shops and conducting commerce. Two examples are the renowned medieval rabbi Samuel Eidels and scholar Joel Sirkes, both of whose surnames end in the Yiddish possessive suffix -s. Eidels was named after a rich woman named Eidel who paid his way through yeshiva, while Sirkes was named for his mother, Sarah.

The matronymic convention can be seen in my surname. Rickin, the anglicized version of Rifkin or Rivkin, translates to “Rivka’s.” Many of the surnames based on women’s names end in the East Slavic possessive suffix -in, including Sorkin (Sarah), Zeitlin (Zeitl), Rochlin (Rachel), Feiglin (Feige), and Dworkin (Dvora).

Overall, because of patriarchal conventions, women are too often left out of genealogical records, making it harder to trace their origins and learn their stories. At the same time, the matronymic naming convention in parts of the Jewish world has allowed women to be more visible than they would have been otherwise.

Thank you, Abby, I’m a fan of great academic libraries & librarians, too. You might find it productive to also connect with the local, national & international JewishGen societies, associations & conferences. Fun & inspiring!

historical family

Very thorough, comprehensive and well constructed Another example of evolutionary practices that can change with social norms Well done