What Does Good Holocaust Education Look Like?

International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which falls on January 27, has always been personal to me; most of my grandmother’s family died in the Holocaust. My grandmother was born in Sighet, the same town as Elie Wiesel, and grew up in Transylvania. She was a very positive person, full of life despite the horrors she endured. She loved to learn and was proud that she spoke five languages fluently.

I was in elementary school in the 1980s, when many of the teachers at my Jewish day school were Holocaust survivors. Some of them told stories of resistance and taught us about the Jewish partisans who fought back against the Nazis. But a lot of their teaching focused on Jews as victims. In sixth grade, I chose the book Night by Elie Wiesel for a book report. The memoir describes how Wiesel, an Orthodox Jew, was transported to Auschwitz as a child, and struggled with his faith as he lost his father and witnessed the loss of humanity of the other prisoners and guards. I was likely too young to take in the harrowing descriptions of life in a concentration camp and the intense experiences of suffering he documented. But my teachers didn’t stop me from reading it, suggest more age-appropriate alternatives, or give me the space to process my emotional reactions to it. As a result, I felt traumatized by reading it.

Overall, the message we received in elementary school was to remember the experiences of the Holocaust, so that it wouldn’t happen again. It was easy, as a child, to take this message literally. I felt it was my personal responsibility not only to remember these stories, but to imagine what the experiences were like as though I had been there myself. It was a heavy burden for a child to bear.

I’m now an elementary school teacher myself, and often consider how to teach kids about the Holocaust without overwhelming them or causing them to experience vicarious trauma, like I did. I want my students to understand the enormity of genocide while also feeling a sense that they have the power to change the world.

Fortunately, since the 1980s, there’s been a shift in thinking regarding the best way to teach children about the Holocaust. Organizations that support teachers, like Facing History and Ourselves and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, emphasize the importance of providing historical context so that the students understand what led up to the Holocaust and made it possible. They also recommend focusing on individual stories and people, rather than numbers, to build empathy.

Though there have always been famous Holocaust memoirs by heroines such as Hannah Senesh and Anne Frank, feminist historians have only recently illuminated some of the stories of women that have been overlooked in favor of male voices or versions of events. These stories document women as leaders, rather than in secondary roles, like many previous accounts.

Judy Batalion’s book, The Light of Days, is made up of such stories. It provides rich accounts of Jewish women in Polish youth movements who challenged the Nazis. Their goal was to rescue fellow Jews, and if that wasn’t possible, then at least “to die with dignity and respect.”

Batalion said she stumbled on these stories only by chance. In the book, she writes that she grew up surrounded by Holocaust survivors who transmitted “an aura of trauma and victimization.” She wrote the book to challenge this narrative and provide other themes for us to consider when teaching the Holocaust, as well as to document the contributions of women in the Holocaust.

Batalion brings a feminist lens to her interpretation of these stories, by pointing out some of the ways gender expectations shaped women’s experiences in the Holocaust. For example, in Poland, Jewish parents tended to prioritize the religious education of their sons, paying for them to attend private Jewish schools, while girls often went to public school and learned Polish and secular studies. During the war, Batalion explains, girls’ facility with Polish became a tool they could use to their advantage to “pass” as Polish and conceal their Jewish identities, allowing them to gain access to a world that would have otherwise been off-limits.

Girls and women were also able to use sexism to their advantage by flirting with the Nazis, Batalion explains, gaining an intimate connection to them which they manipulated to seduce and ultimately kill them. Women in Polish society weren’t expected to be powerful. These patriarchal assumptions afforded Jewish women the freedom to subvert expectations.

Other acts of resistance were spiritual and emotional in nature. Many Jews, like Wiesel, kept their faith in the face of great suffering. Many prisoners in concentration camps forged deep, lasting friendships.

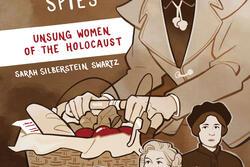

Author and Jewish feminist historian Sarah Silberstein Swartz has also collected stories of acts of resistance by women during the Holocaust, in a recent book titled Heroines, Rescuers, Rabbis, Spies: Unsung Women of the Holocaust. In a JWA interview, she shared that she hoped this book inspired people to continue to remember the Holocaust and to appreciate what women accomplished, not only during the Holocaust, but in their lives afterward.

These and other recent books detailing individual stories of heroism in the Holocaust are an important addition to the Holocaust literature. Batalion's book has been adapted for young adults, making it an ideal classroom resource. Reading her book reminded me of when my Yiddish teacher, Mrs. Zalovitch, told us about how her blonde hair made her look Aryan and allowed her to sneak out of the ghetto to steal food for her friends and family. Another Yiddish teacher taught us to sing the Partisan Song while standing proudly at our desks. I loved the feeling of hope and resistance it inspired in me.

I’ve also thought a lot about Holocaust education as a parent. I didn’t want my daughter to read too much about it when she was too young and be upset by graphic imagery or overwhelmed with grief. This year, the teachers at her Jewish day school carefully prepared her sixth-grade class to listen to a video of a Holocaust survivor by first discussing the emotions of grief and anger they might feel during and after the presentation. This type of trauma-informed education prevents students from becoming overwhelmed and gives them the tools to better process their feelings.

This strategy seemed to work well. Although my daughter had been nervous about listening to the presentation, she later reported it was “interesting and sad,” but did not seem overwhelmed or preoccupied by it. I’m happy that she can also hear stories of resistance, particularly by women, and have a sense of agency to challenge injustices in the world.

In September 2023, Ontario, where I live, will become the first Canadian province to make Holocaust education a mandatory part of the curriculum. In New York, where the legislature made Holocaust education mandatory in public schools in 1994, a bill was signed last year to ensure that this curriculum is being taught. These are positive steps, but the execution is what matters. educators need to consider how they will teach students about the Holocaust in a thoughtful way, particularly given the rise of antisemitism worldwide. I hope they’ll draw on the rich resources available to teach about resistance in the Holocaust, and to include the experiences of the brave girls and women who stood up to the Nazis by helping others, fighting back, or simply staying alive.

I became fascinated with the Holocaust in about Grade 4. I wrote a story from the perspective of a young girl hiding in the hills which won a short story writing contest. I read everything I could get my hands on, including all of Eli Wiesel's books. The Gates of the Forest may have been the one that stuck with me the most. I am still haunted by that story.

I appreciate your thoughts about the best way to deliver this curriculum. You are right -- process is everything here. Facing History and Ourselves is an organization I respect greatly. We need to be sensitive, and we also need to be brave and have these difficult conversations. I believe that allowing students' questions to lead us is an important first step.

When I first began teaching, my teaching partner and I did a year long study of conflict and peace. We started with personal conflict, moved to conflict in narratives, engaged the students in literature circles themed around World War 2 literature, taught about the UN, and ended the year with a trip to New York City (about 30 girls, 10 parents, 2 teachers, a bus, and a hotel in New Jersey). We visited Ellis Island, the UN, and it was a highlight of my career. We may have made mistakes, and I am always learning, but there is no question that what we did together had meaning.

Whenever we teach students about difficult truths, we must also teach them about hope, agency, and how they can make a difference. Everyone a changemaker. Through small acts and large, we can all make a difference.