The Talmud: Repository of Wisdom or Masculine Tool of Oppression? Maggie Anton Weighs In

Writer Maggie Anton, whose "Rashi’s Daughters” series has sold 175,000 copies, believes that studying Talmud is the most feminist thing a woman can do. “Knowledge of Talmud is the key to halacha,” she says. Anton asserts that modern Jewish law is made at a table full of Talmud scholars, and that women can have a seat at that table.

I spoke with Anton while she was staying with me in Palo Alto and lecturing on her research for her new book, Rav Hisda’s Daughter. She spoke at the JCC in Los Gatos, Congregation Beth Torah in Fremont and Congregation Etz Chayim in Palo Alto on October 28th. I am Etz Chayim’s president this year, and, more importantly, I have a spare bedroom.

Talmud study transformed Maggie Anton from a laboratory chemist into an author, and her best-selling series on Rashi’s daughters created a new genre: Talmudic historical feminist fiction.

Anton’s fascination with women of the Talmudic era—which spans 1000 years—began 20 years ago. “I was possessed—POSESSED—to write 'Rashi’s Daughters,'” she said. “After I studied Talmud for a few years, I could not stop thinking about women during that time. They were supposed to have studied along with the men, and supposed to have worn tefillin. I had to find out.”

Anton performed years of research at the UCLA, USC, American Jewish University and Hebrew Union College libraries, and what she learned shaped the "Rashi’s Daughters" series. The primary texts show that women during the 12th century really did wear tefillin and study along with men. Anton has assembled notebooks full of information on the subject, and her research proves that at other points in history women much more actively participated in Jewish ritual and study than they do today.

Anton maintains that the Talmud is the way for Jewish women to have equality. I, however, see it as a tool that is often used to justify misogyny in certain streams of Judaism.

Intrigued? Perhaps you'll like:

As early as fourth grade, at the Kinneret Day School in The Bronx, I was taught that while the Torah was for sharing with the people, the Mishna and Gemara were created as "fences around the Torah." “Fences keep people out,” I assert to Maggie. “The men who wrote the Talmud wrote it to exclude women and regular folk.”

I have never trusted the Talmud because, to me, it is the source of many of the rules and rationalizations that help keep women at the back of the bus and away from microphones at their own awards dinners. Thus, I have long felt that the Talmud endorses misogyny. Not so, Maggie says. “The misogyny and restrictions depend on who is doing the interpretation. It contains both sides of many arguments. The Ashkenazim chose to follow the stricter opinions and the Sephardim chose the more relaxed ones.” She points out that many Jewish scholars have used their interpretations of work by scholars such as Maimonides to justify relegating women to a “supporting role.”

“Women have to keep studying Talmud, because Talmud is the basis of modern Halacha,” Anton says. “Talmud scholars in black coats sit around a table and debate how modern times relate to the Talmud, and if enough women learn enough Talmud, they can get a seat at that table.”

At a recent Bat Mitzvah lunch, I sat down to discuss Anton’s talk with a member of my congregation who is fascinated with Jewish learning and history. His daughter was sitting with us.

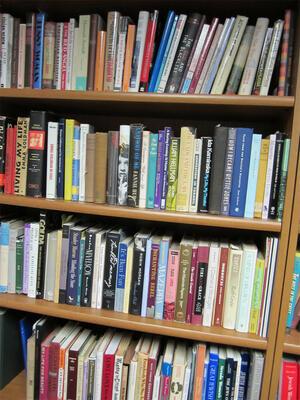

“What book is the Talmud?” she asked. “It’s not one book, it’s a whole shelf full, of books,” I said. The door to our library was open, and I pointed. “It’s right over there, in the library.”

And she went to see.

Rashi's daughters did not wear tefillin, that is totally false in every way, Rashi writes that women should not wear tefillin or tallisim. The author of those books started that ridiculous false rumor.

The full comment I'd like to write would take too long; but I think a critical, immediate point is that now, women are studying Talmud. And Talmud has always involved interpretation. That is how the Jewish people has kept it (and ourselves) alive and modern; and now as even more women--and men--participate, Talmud has the power to demonstrate its relevance for all people.

Maggie, I had no idea there was a feminist commentary on the Babylonian Talmud. I learned a lot from meeting you, and reading your books. And the learning will continue, it seems. May you go from strength to strength.

For me, the challenge to a feminist reading of the Talmud is that women's voices are excluded from the text. The Talmud is an amazing document that records many voices and interpretations across the ages, but they are all male voices (even the few stories of women in the Talmud are told by men). Though I have enjoyed the opportunities I've had to study Talmud and there's something very exciting about its dialogic nature, the absence of women's voices and perspectives gets in the way for me and eventually becomes a distraction.

In reply to <p>For me, the challenge to a by jrosenbaum

Apparently there are now women who are ruling on Jewish issues in the Orthodox communities. If the world continues to evolve, there may come a day when there is a new volume of the Talmud which contains their voices as well.

In reply to <p>For me, the challenge to a by jrosenbaum

Of course the Talmud is composed by men for men; what else would you expect from the first millenium? But it is the text that underlies 1500 years of Jewish laws and traditions. Feminists who ignore Talmud or say it has no relevance for Jews today do so at their peril, however they may be relieved to know that Israeli Talmud scholar Tal Ilan is editing a new series, "A Feminist Commentary on the Babylonian Talmud." Either five or six volumes have been published and the goal is to have one on each Talmudic tractate.

One of the challenges, and pleasures, of Talmud study is how open the text is to interpretation, or reinterpretation. Minority opinions are presented as valid, and one is free to follow the sage whose opinion one prefers.

The bottom line is that knowledge is power, and women's exclusion from Talmud study has left us powerless to challenge the halacha that disadvantages women. Preevia mentions my saying that halacha is made by men in black coats sitting around a table from which we/women are excluded. But at the rate that women, especially in the Orthodox world, are studying Talmud, I don't think it will be long before women in black dresses are sitting around that table too. And I have no doubt that Jewish Law will not only look different, but better.

www.maggieanton.com

I haven't read Anton's books Rashi's Daughters and now with this excellent commentary by Preeva I am curious to see what this is all about. Carole K.

I read Maggie Anton's Rashi's Daughters trilogy and am currently halfway through Hisdah's Daughter. I have enjoyed (am enjoying) all of her books. Preva, I liked the exchange you had with Maggie about Mishna and Gemara. Carolyn S.

In reply to <p>I read Maggie Anton's by Anonymous

Maggie really knows her stuff. So I can see her point that you have to really study it to properly refute a lot of the arguments that are made in the name of Talmudic reasoning. But since there are SO MANY views expressed in the Talmud, people tend to choose one interpreter and follow them. And that's where the problem starts. Since there are never any conclusions in Talmud, only opposing viewpoints, people pick and choose what they want to follow. And then beat other people over the head with quotations taken out of context.