Susan B. Anthony's Secret Pro-Life Agenda

Part 3 of the series Reading Our Rights.

Did you know that Susan B. Anthony was a bomb-throwing pro-life crusader who believed that aborting babies was tantamount to murder?

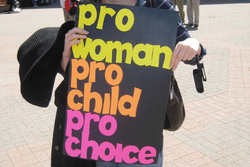

Neither did I, but the co-opting of Anthony as a symbol of the anti-abortion movement is one of the most tired tactics of anti-choice activists. This is what always happens when people with a strong stake in a current social movement look to the past to validate their positions. They pick and choose, looking for the figure who was proven to be on the right side of history to act as a symbol of their movement and beliefs. The problem is that the history of any social movement is murky, poorly understood, and hotly contested—even more so when we're talking about something as controversial as abortion.

And yet, we cannot allow myths about the past to shape how we view today's movements. To that end, I set out to try to unearth the history of abortion and reproductive choice in America. Who are the ancestors of the current pro- and anti-choice movements? And what was the state of abortion in the America of yesteryear?

It turns out that, perhaps unsurprisingly, different sources emphasize different aspects of this history. The first stop on my historical journey was Leslie Reagan's When Abortion was a Crime, which details the history of abortion from 1867 to 1973, as well as Katha Pollitt's 2014 book Pro, which draws on many of the same historical arguments as Reagan. In Pollitt's and Reagan's tellings, in the early years of American history, abortion was perfectly legal until the quickening, which is an old-timey way of saying that it was legal until the fetus started moving. Back then, even the Catholic Church implicitly accepted these early-term abortions, as Catholics believed that babies became ensouled once they started moving. In those days, herbs, potions, and other abortifacients abounded, as everyone from respectable midwives to dastardly charlatans trotted out miracle cures for unwanted pregnancies.

These miracle cures often turned out to be poisonous, and in the 1820s and 1830s, the first laws against the sale of these drugs started cropping up, purely for poison-control reasons. Then, the mid-nineteenth century saw the beginnings of the ideological battles for and against abortion. The chief driving force against abortion was the medical establishment—but not for any moral reason. Doctors wanted to ban abortion as a way to take away the authority of the (female) midwives who often provided this service. As immigrants flooded into the United States in the 1840s and 1850s, nativists started making noise about banning abortion, fretting about upper middle-class WASP women terminating pregnancies while hordes of European immigrants reproduced with abandon. Meanwhile, early feminists—yes, maybe even Susan B. Anthony, although no one actually knows for sure—were also iffy about abortion, because—wait for it—they knew that the threat of unwanted children was one of the only ways that wives could stop their husbands from raping them with impunity. It seems pretty clear the modern-day co-opting of Anthony’s purported anti-choice stance is an opportunistic, and perhaps intentional, misreading of her historical context. Anthony was agitating for women’s rights, and the protection of women at a time when it was considered more reasonable to make abortion, rather than marital rape, a crime.

These anti-abortion attitudes soon made their way into state’s legislatures. In 1821, Connecticut became the first state to pass a statute against later-term abortions. As the century progressed, more and more states passed similar laws prohibiting later abortions. The prohibition of all abortions, and the imposing of stricter penalties on violators, culminated in the 1873 Comstock Law, which made it illegal to even share information about abortion or birth control.

So, it's 1874, and abortion is illegal. Does that mean that it was rare, clandestine, and exclusively done in back alleys with coathangers? Not so fast, says Reagan. Although abortion was criminalized in the 1870s, many of the doctors who had advocated for its criminalization continued providing it, especially if their patients happened to be wealthy, well-connected white women. By some accounts, said Reagan, there were two million abortions per year in America during this time period, far more than today. So if physicians continued to provide abortions even after criminalization, then why did they push for anti-abortion laws in the first place? Reagan's answer to that is perhaps not surprising. She theorizes that physicians and other social leaders pushed for criminalization because of the age-old impulse to shame women for sex. The undercurrent here was one of stigma, of punishment for articulating a desire to have sex without any lasting punishment or consequence. In this argument, we see the germination of today's frenzied, moralistic anti-choice rhetoric.

Women continued having abortions in the early twentieth century, but the 1940s and 1950s saw the advent of the dangerous, coathanger-in-the-alley era of abortion that we today associate with the period of illegality. Predictably, wealthy white women could still usually obtain a so-called “therapeutic abortion,” a vaguely defined term that had to do with the health of the mother; they could also go before hospital committees to plead their case for an abortion. But the vast majority of abortions in this time period were desperate and dangerous, especially for poor women and women of color--a dynamic sadly reminiscent of today’s America, in which low-income women often struggle to find the time, resources and support necessary to reach an abortion clinic and obtain the service that’s ostensibly legally available to all.

Finally, the absurdly high mortality rates stemming from illegal abortion, combined with the relaxing sexual mores of the 1960s, led physicians, civil liberties lawyers, and early feminists to the fight for Roe v. Wade, which passed in 1973 and brought abortion full-circle back to the legal status it had enjoyed in the early days of American history.

Unfortunately, that's not the end of the story, is it? Legalized abortion is not necessarily enshrined into the framework of our society and this basic human right feels more vulnerable to attack than ever. That unfortunate truth led me to another question, an essential one to understanding this medical procedure’s place in our society: Outside of religious objections from the Catholic Church—which weren't even codified until the late nineteenth century—where did the moralistic, you're-killing-babies, anti-choice mindset come from?

Conventional wisdom has it that this mentality sprang up after Roe v. Wade. However, the next stop on my Abortion History Tour (coming soon to a town near you!) was with a book that claims otherwise. In his book, 2016's Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement Before Roe v. Wade, Daniel K. Williams argues that, just like the secret history of abortion in America, the anti-choice movement also has its own secret, unexpected history. He argues that the anti-choice movement actually started among working-class New Deal liberals who believed that many women obtained abortions due to poverty and advocated for more social support programs for new mothers. He opines that in the years leading up to Roe v. Wade, anti-choicers from a diverse set of groups—from Orthodox Jewish rabbis to Harvard-educated physicians—spoke out against abortion, taking the language of universal human rights used by Civil Rights activists and feminists and applying it to the rights of fetuses. These activists argued that anyone who valued rights and support for the poor, weak, and downtrodden should extend their protection to society’s most vulnerable “people,” aka the unborn. The political lines of the debate in the 1960s also looked different then than they do now. In those days, many Republicans were pro-choice (for example, Williams points out that Ronald Reagan signed what was then the most liberal abortion law in the country when he was governor of California in 1967) and many of these anti-choice activists were Democrats. It was only after Roe v. Wade, when some Democratic Party leaders chose second-wave feminism over anti-choice platforms, that the anti-choice movement fled to the Republican party and became the virulent, conservative movement that we know today.

A sidenote: one of the central claims of Williams' book is that the pro-life movement before Roe v. Wade was solely concerned with human rights, and had no connection to shaming and policing women's sexuality. I'm going to go out on a limb and take exception with that idea: as we've already seen, by the mid-nineteenth century, abortion restrictions were already in place as a way to shame and control women. That kind of rhetoric, and the attendant ideas behind it, don’t just go away. Even if the anti-choice activists of the 1930s and 1940s believed that they were fighting for universal human rights—and I'm sure some of them did believe that—these people weren't born and raised in a vacuum without any influence or input from a society that has been policing and regulating women's sexualities since day one. It's specious to claim that these actors were only motivated by what they said in their speeches, while ignoring the long social history that has sought to control women through any means necessary.

Williams' arguments, and my umbrage with them, simply illustrate a larger point: so much of social history is clandestine; so much of it happens in the private sphere, or even in the mind of individuals, and it's impossible to ever fully understand the whole context that prescribes the mores and practices of a different era. Perhaps, then, it's futile to even try to map the ideologies of the nineteenth century onto today, or to co-opt the past's figureheads and their arguments for our own purposes. For me, the most instructive aspect of my mini-tour through the history of abortion was seeing how much times have changed. Yes, the undercurrent of shaming women for their sexual choices has stayed constant, but aside from that, the ideological players and main arguments have realigned and shifted so much over the years that today’s abortion debate would likely be unrecognizable to a time traveler from 1850. If anything, this constant realignment gives me hope that the terms of today's debate are not static, that if feminists, physicians, and Democrats can flip on abortion, if new information and perspectives can change minds, then this isn’t a conversation that will go in circles but will instead move forward into a deeper understanding of women’s bodily autonomy.

It gives me hope that a century from now, some blogger on a spaceship will stumble on a Mind Kindle article about that crazy early-twenty-first century era when anti-choice activists tried to prioritize the life and health of a zygote over the life and health of a living woman. In this fantasy, the spaceship blogger will chuckle to herself, and make note of the crazy past and how different everything once was, and then she'll navigate away from the article and move on.

Love Emily's piece? Let us know and get an alert each time the next Reading Our Rights post goes live!

Great look at HERstory add part of our larger history. Thank you.